Controversial_Ideas 2022, 2(1), 5; doi:10.35995/jci02010005

Article

“Men” and “Women” in Everyday English

Author email: mawiee@protonmail.com

How to cite: Jarvis, E. “Men” and “Women” in Everyday English. Journal of Journal of Controversial Ideas 2022, 2(1), 5; doi:10.35995/jci02010005.

Received: 25 November 2021 / Accepted: 11 April 2022 / Published: 29 April 2022

Abstract

:What kind of distinction are the words “men” and “women” used to mark in everyday English—one of biological sex, social role, or something else, such as gender identity? Consensus on this question would clarify and thereby improve public discussions about the relative interests of transgender and cisgender people, where the same sentence can seem to some to state an obvious truth but to others a logical or metaphysical impossibility (“Transwomen are women” and “Some men have cervixes” are topical examples). It is with this in view that I report here the results of five recent surveys.

Keywords:

Sex; Gender; EnglishWhat kind of distinction are the words “men” and “women” used to mark in everyday English—one of biological sex, social role, or something else, such as gender identity? Consensus on this question would clarify and thereby improve public discussions about the relative interests of transgender and cisgender people, where the same sentence can seem to some to state an obvious truth but to others a logical or metaphysical impossibility (“Transwomen are women” and “Some men have cervixes” are topical examples). It is with this in view that I report here the results of five recent surveys.

The surveys were a main survey, a follow-up survey, and three surveys to check for response bias. My plan is to introduce the first two surveys sequentially and the final three in parallel, before rounding off with a brief discussion. For convenience only, I shall use “male” and “female” to denote biological sex, and “masculine” and “feminine” to denote social role.

Main Survey

For the main survey, four hundred participants were presented with a passage of text describing a fictional country in which biological sex and social role were aligned atypically: male sex with feminine role, and female sex with masculine role (as these categories are commonly understood).1 They were then asked by means of a multiple-choice question—any one from a pool of eight, fifty participants per question—to identify the men or the women in that country with the feminine males or the masculine females.

Here is the passage of text, followed by the pool of questions and the answer options:

Dianesia is a country in the South Pacific where every adult falls into one or other of two distinct groups.

In one group are the breadwinners. They’re competitive by nature and have relatively high social status. They dress in trousers and wear their hair short. They have vaginas and ovaries, and XX chromosomes.

In the other group are the childcarers. They’re compassionate by nature and have relatively low social status. They dress in skirts and wear their hair long. They have penises and testicles, and XY chromosomes.In Dianesia, are the women the breadwinners?In Dianesia, are the men the breadwinners?In Dianesia, are the women the childcarers?In Dianesia, are the men the childcarers?In Dianesia, do the women have vaginas?In Dianesia, do the men have vaginas?In Dianesia, do the women have penises?In Dianesia, do the men have penises?⭘ Yes⭘ No⭘ Can’t say

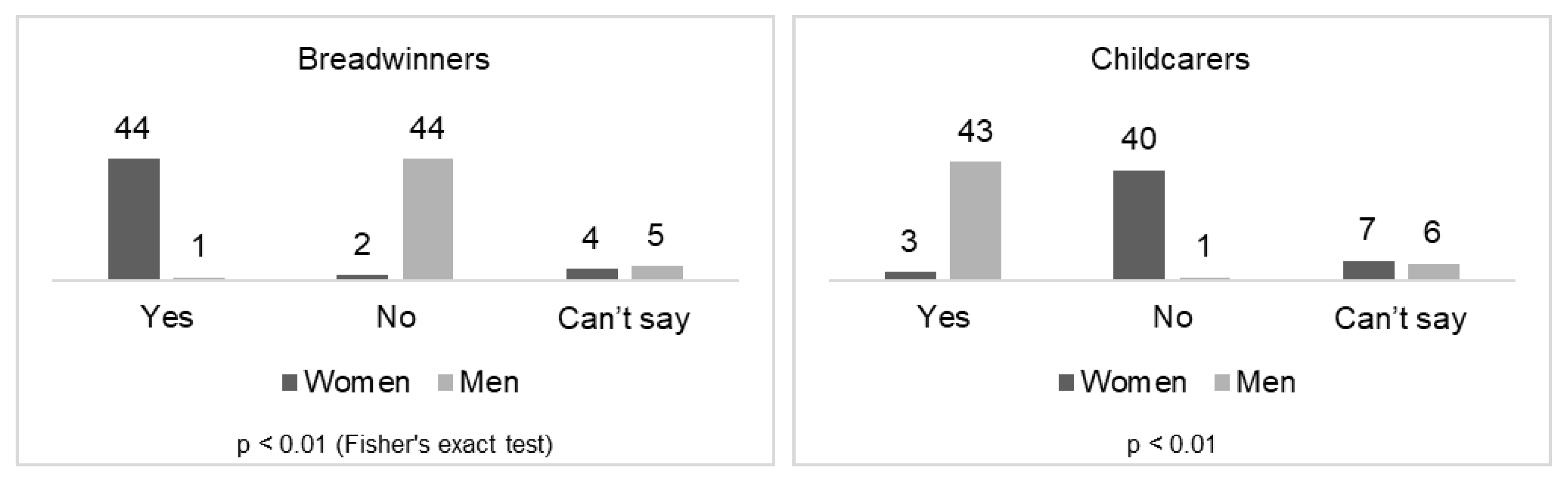

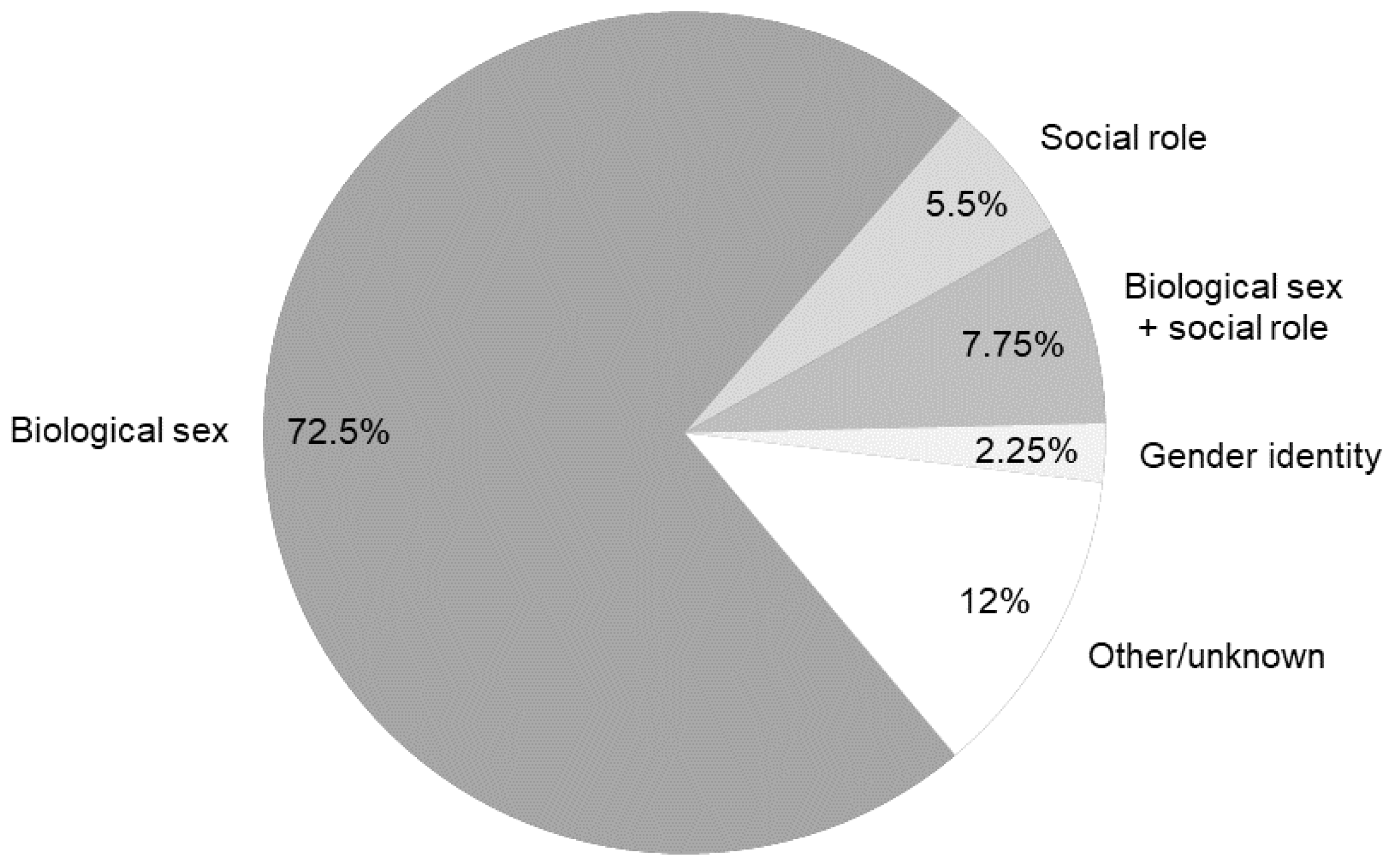

The answers given to the eight questions are summarised in Figure 1. In total, two hundred and ninety participants (72.5%) answered that the men were the feminine males and the women the masculine females, twenty-two (5.5%) answered that the men were the masculine females and the women the feminine males, and eighty-eight (22%) answered “Can’t say”.

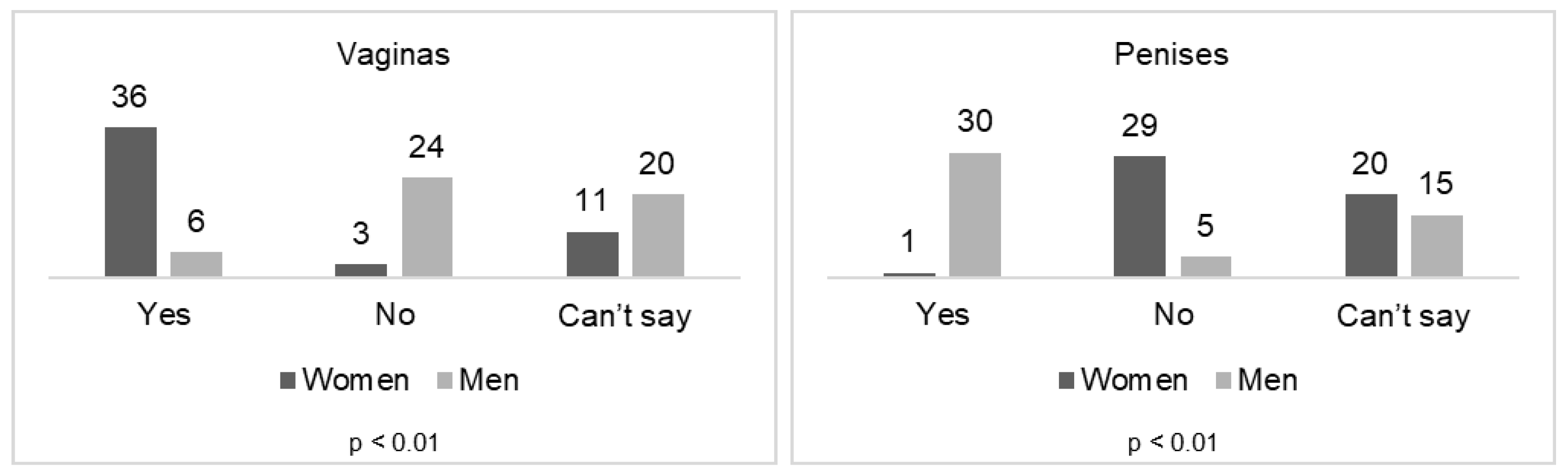

Participants were also asked for their age ranges and levels of education. Figure 2 shows the number of participants within each demographic group, together with the percentage of participants within each group who answered that the men were the feminine males and the women the masculine females. The lowest of those was 58%.

These results suggest that different people use “men” and “women” to mark different distinctions, but the majority use them to mark a distinction of biological sex. Moreover, this holds across all the demographic groups, so that even adjusting for over- and under-representation would not change the overall picture. However, the unexpectedly high number of “Can’t say” answers—particularly for the questions about anatomy—is consistent with several competing explanations, which the follow-up survey was designed to explore.2

Follow-Up Survey

All eighty-eight participants who had answered “Can’t say” in the main survey were invited to take part in the follow-up survey, and sixty responded. This time biological sex and social role were aligned typically (male sex with masculine role, and female sex with feminine role), and participants were asked the same questions as they had been asked in the main survey, so that the two sets of answers could be compared.

This is the passage of text:

Dianesia is a country in the South Pacific where every adult falls into one or other of two distinct groups.

In one group are the breadwinners. They’re competitive by nature and have relatively high social status. They dress in trousers and wear their hair short. They have penises and testicles, and XY chromosomes.

In the other group are the childcarers. They’re compassionate by nature and have relatively low social status. They dress in skirts and wear their hair long. They have vaginas and ovaries, and XX chromosomes.

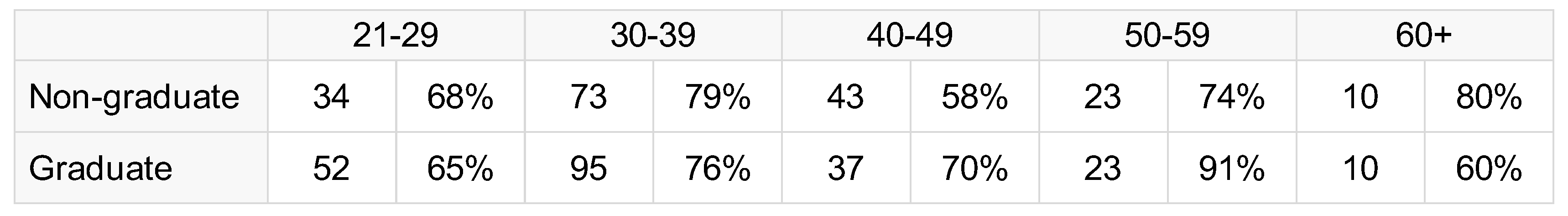

Figure 3 compares the answers given in the follow-up survey with the answers given in the main survey. Thirty-one participants (7.75% of the original four hundred) answered that the men were the masculine males and the women the feminine females, and twenty-nine answered “Can’t say” once again.

Those twenty-nine participants were then asked an open-ended question:

What further information would enable you to answer “Yes” or “No”?

Nine (2.25%) said that they would need to know the Dianesian people’s gender identities. Of the remaining twenty, fifteen answered that they would need explicit definitions of “men” and “women”, while the other five said that they were unsure, or failed to address the question.

These results suggest that the people who use “men” and “women” to mark a distinction of biological sex are in a greater majority than was apparent from the main survey: as well as those who use the words to mark a distinction of social role, there are those who use them to mark a distinction of combined biological sex and social role, and those who use them to mark a distinction of gender identity. The results presented so far, however, are vulnerable to charges of response bias, and the final three surveys were intended to address this.

Checks for Response Bias

For each of the checks for response bias, one hundred further participants (fifty per question) were presented with a variation on the passage of text, the questions, or the answer options, and their answers compared with the answers from the main survey. The first two checks were for order effects, and the third was for effects of question wording, specifically the possible interpretation of “the women” and “the men” as referring only to typical women and men.3

In the first check, the order of the answer options was reversed:

In Dianesia, are the women the childcarers?

In Dianesia, do the women have penises?⭘ Can’t say⭘ No⭘ Yes

In the second check, the positions of the sentences about social role and the sentences about biological sex were reversed:

In one group are the people with vaginas and ovaries, and XX chromosomes. These are the breadwinners. They’re competitive by nature and have relatively high social status. They dress in trousers and wear their hair short.In the other group are the people with penises and testicles, and XY chromosomes. These are the childcarers. They’re compassionate by nature and have relatively low social status. They dress in skirts and wear their hair long.

In Dianesia, are the women the childcarers?In Dianesia, do the women have penises?

In the third check, two of the questions about “the women” were replaced with questions about an individual:

Oliana is a Dianesian woman. Is Oliana one of the breadwinners?Oliana is a Dianesian woman. Is Oliana one of the childcarers?

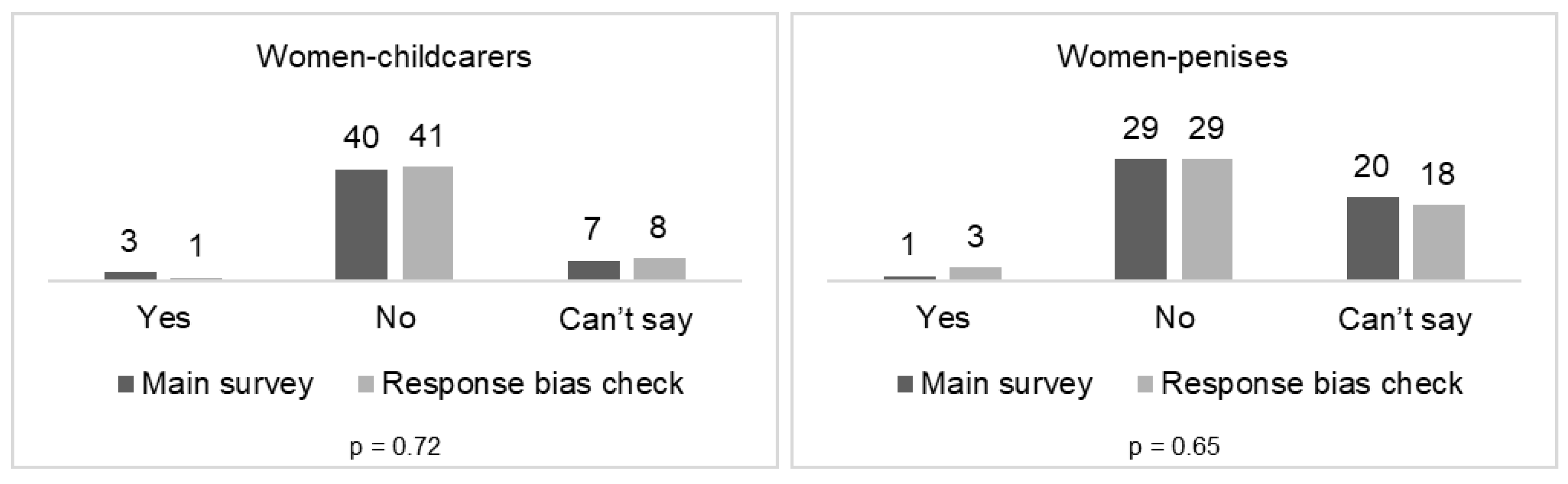

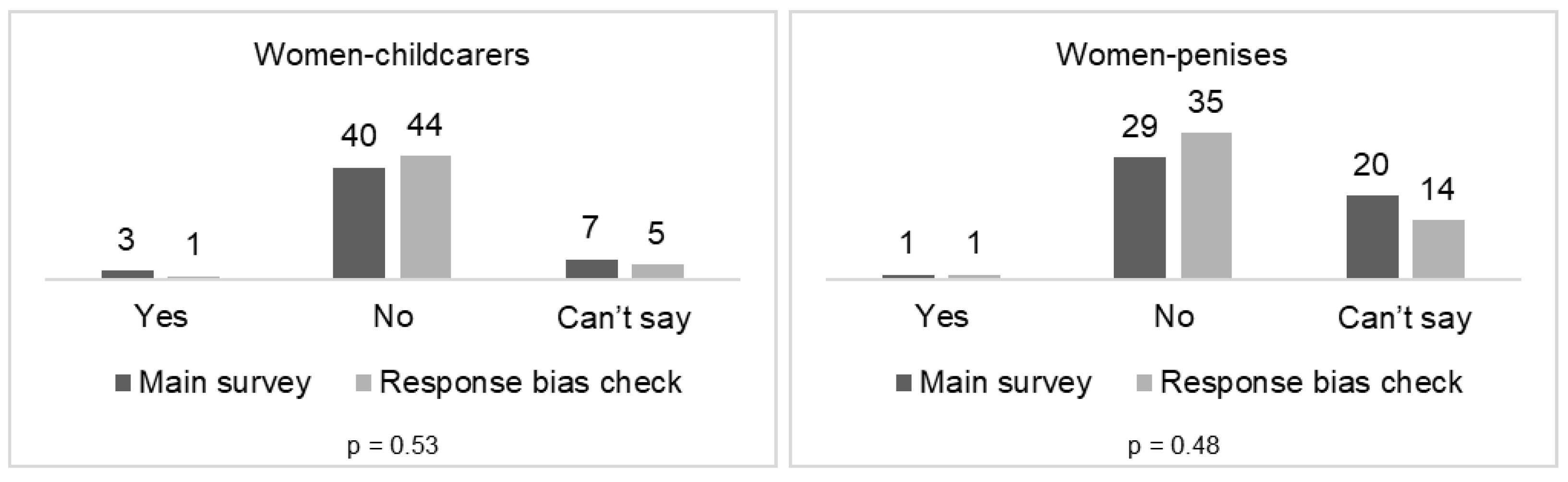

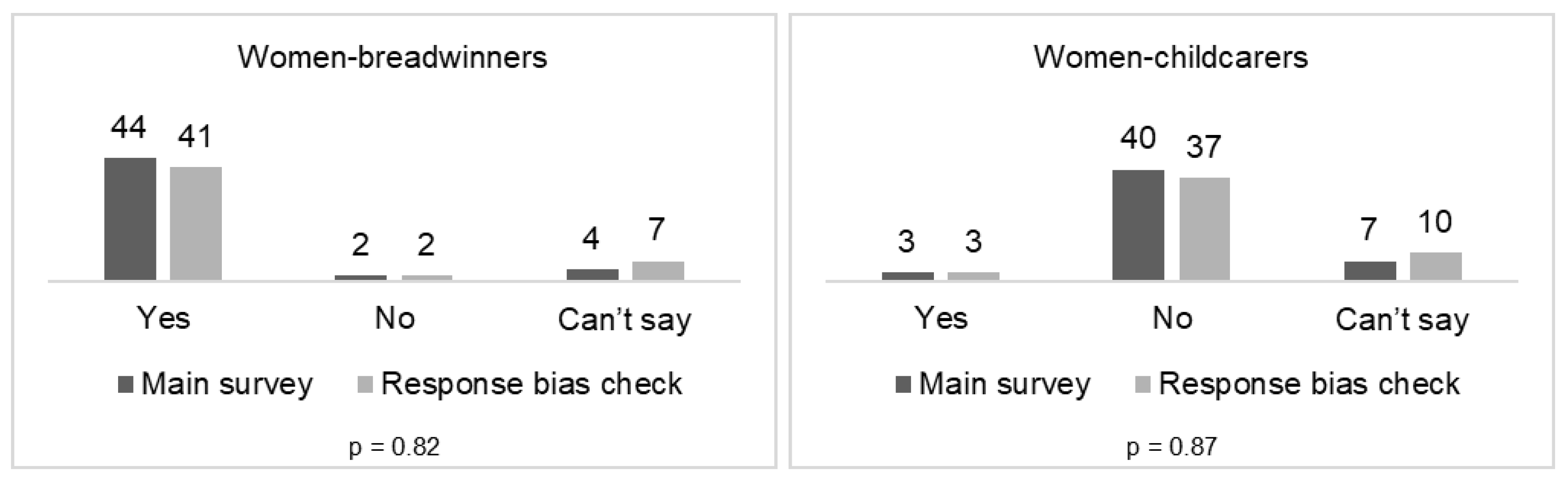

The results of the three surveys are shown in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6. In each case, there was no significant difference from the results of the main survey. Hence, no response bias was detected.

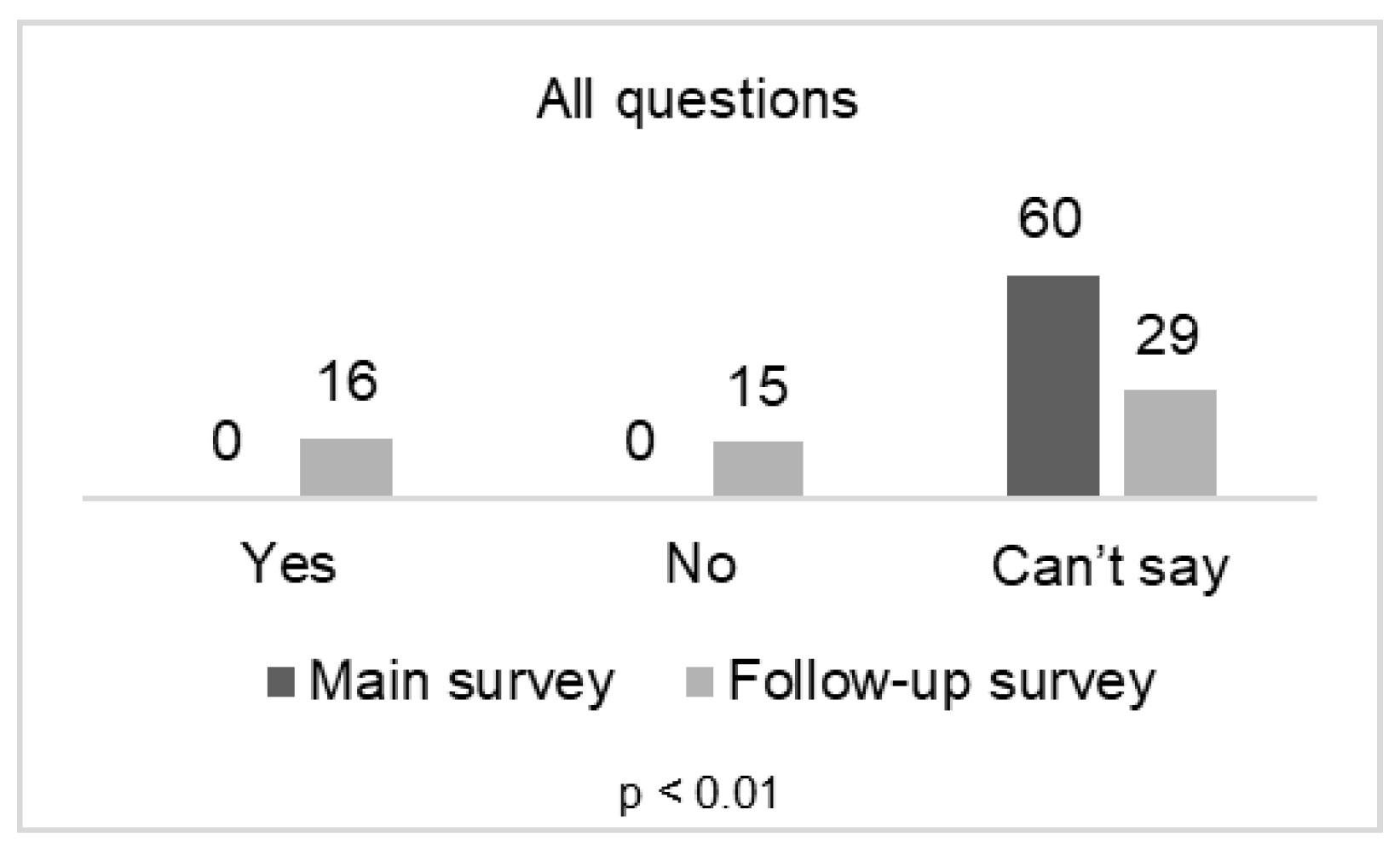

Figure 7 summarises the results of the main and follow-up surveys. I now draw the provisional conclusion that the words “men” and “women” are used predominantly in everyday English to mark a distinction of biological sex.

That this conclusion is not universally obvious is consistent with evidence from several areas of public life: health websites tell us that man and woman are genders, which are distinct from the sexes male and female;4 the World Health Organization tells us “People are born female or male, but learn to be girls and boys who grow into women and men”;5 politicians are unable to define “woman” in a way that reflects how most people use the word, if they are able to define it at all;6 newspaper articles describe a male sex-offender as “a woman” but make no allusion to the person’s biological sex;7 the Wikipedia entry for “Trans man” begins “A trans man is a man who was assigned female at birth”.8 In these cases, as in others, it cannot be ruled out that the root cause is the desire to influence usage for political ends, but neither can it be ruled out that the cause is ignorance of how words are at present most widely used.

Further work in the same vein as that described here would, of course, benefit from larger sample sizes and wider ranges of participants.9 A variety of different wordings would also be of value, particularly wordings for which answers of “Yes” and “No”, rather than “Can’t say”, would suggest a distinction of gender identity. Meanwhile, more focused work might seek to establish which sex characteristics are relevant to the biological sex distinction, whether the distinction is exhaustive, whether it is vague, and so on.

I shall finish by indicating some of the ways in which this work might be of interest within analytic philosophy. Since the ultimate importance of everyday English to analytic philosophy is a point of contention, my comments should be received as suggestions that readers can take or leave according to their own views of the subject. I do not wish to take sides.

First and foremost, the five surveys can be regarded as contributions to the sub-branch of experimental philosophy that has been dubbed “experimental analysis”:10 the use of controlled thought experiments with samples of ordinary people in the analysis of folk concepts. Although I framed participants’ responses as illustrating their usages of the words “men” and “women”, I could equally have framed the responses as exhibiting their concepts <man> and <woman>.11

Second, the results might be of interest to those who hold that the concepts expressed by “men” and “women” in everyday English are not what they seem to be,12 or to those who hold that they should not be what they are (namely conceptual engineers who wish to improve or replace existing concepts for ethical reasons).13 In each case, the results can provide an empirically grounded point of reference.

Finally, there are occasions when philosophers wish to speak about everyday English usage but are concerned about the adequacy of dictionary entries for their purposes. One concern is that dictionary entries include valuable but non-essential information as well as definitions in the strict sense;14 another is that dictionary entries focus on paradigms to the neglect of borderline cases.15 The results presented here can help with both of these concerns.

Figure 1.

Main survey.

Figure 2.

Answers per age range and level of education.

Figure 3.

Follow-up survey.

Figure 4.

Check for response bias (order of answer options).

Figure 5.

Check for response bias (positions of sentences).

Figure 6.

Check for response bias (question wording).

Figure 7.

Summary of main and follow-up survey results.

| 1 | Participants were recruited via Prolific (www.prolific.co). They were required to be aged twenty-one or above, and to have English as their first language, but were otherwise self-selecting. |

| 2 | The different numbers of “Can’t say” answers for the questions about anatomy and the questions about occupation might have been due to demand effects, but this is speculative. |

| 3 | An analogy is the question “Do cats have four legs?”, which might be answered in the affirmative even though many cats have lost legs through injury or surgery. |

| 4 | e.g., K Clements. “What’s the difference between sex and gender?”. Healthline, accessed 29 March 2022, https://www.healthline.com/health/sex-vs-gender. |

| 5 | WHO. “Gender: definitions”. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, accessed 29 March 2022, https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-determinants/gender/gender-definitions. |

| 6 | See H Zeffman. “Labour’s Yvette Cooper shies from ‘rabbit hole’ transgender question”. The Times, 9 March 2022, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/cooper-shies-away-from-labour-s-transgender-rabbit-hole-kcf0kzghf. |

| 7 | e.g., S Murphy. “Northwich woman jailed for cocaine-fuelled sex with a dog”. Northwich Guardian, 22 December 2021, https://www.northwichguardian.co.uk/news/19802592.northwich-woman-jailed-cocaine-fuelled-sex-dog. |

| 8 | Wikipedia. “Trans man”. Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, accessed 26 March 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trans_man. |

| 9 | On this note, an anonymous referee queried the omission of participants aged under twenty-one from the surveys. The reason for the omission had been pragmatic, but to address the concern I replicated the main survey with one hundred participants aged between eighteen and twenty, limiting the questions to “… are the women the childcarers?” and “… do the women have penises?”. 62% of the participants answered that the women were the masculine females, and 11% that they were the feminine males. |

| 10 | T Nadelhoffer & E Nahmias. “The past and future of experimental philosophy”. Philosophical Explorations, 10(2) (2007), 123–149: 126. |

| 11 | Even for those who do not trust the responses of non-philosophers, the scenarios and questions might provide food for reflection, as they might for those who reject the conceptual/linguistic view of philosophy altogether. cf. A Byrne. “Are women adult human females?”. Philosophical Studies, 177 (2020), 3783–3803: 3789. |

| 12 | e.g., E Diaz-Leon. “Woman as a politically significant term: a solution to the puzzle”. Hypatia, 31(2) (2016), 245–258; S Haslanger. “What are we talking about? The semantics and politics of social kinds”. Hypatia, 20(4) (2005), 10–26. |

| 13 | e.g., E Barnes. “Gender and gender terms”. Noûs, 54(3) (2020), 704–730; K Jenkins. “Amelioration and inclusion: gender identity and the concept of woman”. Ethics, 126 (2016), 394–421. |

| 14 | A Byrne. op. cit.: 3786. |

| 15 | M Heartsilver. “Deflating Byrne’s ‘Are women adult human females?’”. Journal of Controversial Ideas, 1(1) (2021), 9: 13. |

© 2022 Copyright by the author. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).