Controversial_Ideas , 5(2), 6; doi:10.63466/jci05020006

Article

From Worriers to Warriors: The Cultural Rise of Women

1

Social Sciences Division, New College of Florida, Sarasota, FL 34243, USA

*

Corresponding author: coclark@ncf.edu

How to Cite: Clark, C.J. From Worriers to Warriors: The Cultural Rise of Women. Controversial Ideas 2025, 5(Special Issue on Censorship in the Sciences), 6; doi:10.63466/jci05020006.

Received: 17 April 2025 / Accepted: 19 July 2025 / Published: 27 October 2025

Abstract

:For the first time in history, women hold substantial cultural and institutional power. Men and women differ, on average, in their values: women are more harm-averse, equity-oriented, and prone to resolving conflict through social exclusion. As a result, shifting sex compositions can bring palpable cultural change. The transition has been particularly dramatic in academia, where women were once almost entirely excluded and now constitute majorities. I review research showing that sex differences in self-reported academic priorities correspond to recent institutional changes, including (i) preference for equity (e.g., DEI initiatives, grade inflation), (ii) prioritization of harm-avoidance (e.g., trigger warnings, safe spaces), and (iii) increased ostracism (e.g., cancel culture). I then expand my analysis to other trends that may be partly attributable to the ascendancy of women, including the rapid success of the LGBT community, animal rights progress, rising mental health concerns, and increased accountability for competent but unethical leaders. Women, once dubbed “worriers” by evolutionary scholars, participate in culture as warriors for justice. This inflection point offers an opportunity to examine the costs and benefits of both the male-oriented status quo and the emerging female moral order, so that societies may draw on the best aspects of both.

Keywords:

evolved sex differences; sex ratio; feminization; academia; censorship; equity; merit; ostracismFrom plant-based diets, body positivity, and LGBT pride, to grade inflation, participation trophies, and safe spaces, and to “cancel culture,” #MeToo, and DEI initiatives, many cultural movements over recent decades have something in common: they reflect the values and priorities of women. Just 70 years ago, women had virtually no representation in most culturally important institutions. As recently as 50 years ago, women were still vastly outnumbered and often relegated to roles with little influence. But in the past few decades, women have made remarkable progress and have even surpassed men in many domains. Given that men and women have different values and priorities on average, these dramatic and rapid shifts in the sex ratio of important institutions have likely had significant consequences.

I contend that the ascendancy of women is a primary cause of many cultural trends that have been subject to intense discussion in recent years and often attributed to other causes, such as “wokism” (e.g., Young, 2024) or “coddling” (Lukianoff & Haidt, 2019) (both of which, I suspect, can also be attributed in part to the ascendancy of women). Although I have opinions regarding which changes have been positive, negative, or a mix of both, I do not aim to adjudicate the desirability of these changes. Instead, I forward a descriptive argument, focusing primarily on academia as a case study but then expanding my analysis to other domains.

I close by recommending we take advantage of this period of conflict as increasingly powerful female values clash with a male-oriented status quo. Just as we’ve long worked to curb the antisocial impulses of men, societies can learn to mitigate any potential downsides of female tendencies. By identifying which norms work best in which contexts, societies may benefit from the best aspects of both male and female psychology.

1. The Worriers and the Warriors

Men and women achieve reproductive success in different ways, and so men and women evolved different psychological proclivities (Geary, 2021).1 To pass on their genes, women needed to prioritize both their own survival and that of their children (Campbell, 1999). Because of the extended helplessness and vulnerability of human offspring, nine months of pregnancy was not enough – women had to survive for many years to nurture and protect their children. Women thus evolved to (i) have higher concern for vulnerable others, and (ii) avoid risks, by preferring kin (those most likely to have their interests at heart), befriending highly trustworthy and equal status others (those who pose no competitive or aggressive threats), and eliminating from their social world anyone who did present risks. For men to pass on their genes, they needed to gain access to women. They did so by (i) competing against peer men to attract women and to gain status and deference from other men and (ii) cooperating with peer men to defeat outgroup men and gain access to their resources and women (e.g., Buss, 1988; Puts, 2010). Men thus evolved to compete in status hierarchies, by displaying competence to their peers, identifying and cooperating with skilled others, and building large coalitions to compete effectively against and defeat enemy groups.

In one particularly cute demonstration of sex differences, Joyce Benenson et al. (2019) had children ages 3–5 evaluate two colorings of a house – one messy and one neat – and asked the children how many stickers they wanted to award each coloring. Boys were more likely to award more stickers to the neat coloring, whereas girls were more likely to award the same number of stickers to each coloring. These findings suggest an early preference among males toward rewarding merit and an early preference among females toward creating equitable outcomes. Benenson (2014) has extensively documented sex differences from preverbal infants through young adult men and women and provides a useful and memorable framework, describing men as the “warriors” and women as the “worriers.” Here, I outline a subset of her results that are particularly relevant to recent cultural changes.

Relative to females, males prefer and play more in groups (Benenson et al., 1997), have larger social networks (Benenson, 1990), are more tolerant of genetically unrelated peers (Benenson et al., 2009), engage in more post-conflict affiliation (Benenson et al., 2018; Benenson & Wrangham, 2016), focus more on the abilities of their peers (Benenson, 1990), and are more inclined to reward merit (Benenson et al., 2019). Boys and men display their skills to outcompete peers and climb merit-based hierarchies while also trying to impress and attract their peers to form large cooperative and competent coalitions. Competitions and conflicts determine who goes up and down in status, but they tend not to result in the termination of alliances between ingroup competitors. Maximally large and competent social groups provide substantial competitive advantage in coalitional conflict, and so if a peer has competencies to contribute to the group effort, it is better to keep that peer around.

Relative to males, females prefer dyads (Benenson, 1993), find large groups aversive (Benenson et al., 2008), reduce group size via ostracism (Benenson et al., 2013), have more fragile friendships (Benenson & Christakos, 2003), prefer to perform equal to (vs. better than) same-sex friends (Benenson & Schinazi, 2004), focus more on the kindness of their peers (Benenson, 1990), distribute awards equally (Benenson et al., 2019), and display more empathy and willingness to help victims (Benenson et al., 2021). Girls and women are motivated to care for vulnerable others and to ensure their ability to do so by enforcing equity and avoiding and eliminating risks – such as higher status peers, lower status (and thus potentially jealous) peers, competitive peers, and otherwise morally suspect peers – from their environments (Benenson, 2013). Competitions and conflicts are avoided, but if they do occur, relationships may never recover. Women aim to pare down and purify their social worlds to selected trustworthy others, those who will directly aid their survival and pose little to no risk to their status or well-being.

Sex differences, including the psychological and the physical, refer to group averages and range in size. For some, the full distributions of men and women overlap substantially, and for others, very little. And plenty of men and women have priorities more similar to the opposite sex. However, sex differences are also correlated. So, just as male and female faces are more easily differentiated than male and female eyes, full psychological profiles should be more easily discernible as male and female than just, say, preferences for equity. And rapid and radical shifts in the representation of those psychological profiles (e.g., 98% male and 2% female to 40% male and 60% female) could generate noticeable changes – perhaps very noticeable changes.

2. Historical Exclusion of Women and the Male Status Quo

Until recently, women were largely excluded from the roles and institutions that shape culture. In the United States, women did not surpass 10% representation among state legislatures until 1979, the House of Representatives until 1993, the Senate until 2001, state governors until 2003, and CEOs of Fortune 500 companies until 2023 (Schaeffer, 2023). Although we have yet to see a female President of the United States, other leadership domains are trending toward increased representation of women. Similar patterns pertain in virtually all institutions. For example, even though girls and women have a writing advantage over boys and men (Reilly et al., 2019), historically, they were excluded from journalism. In the 1950s, The New York Times (likely ahead of the curve on inclusion of women) segregated female reporters away from the main newsroom to write on “Food, Fashions, Family, Furnishings.” In the 1970s, the Times was sued for discrimination against women in top newsroom and corporate jobs (Svachula, 2018). As of 2023, women made up the majority (55%) of all Times staff and all Times leadership (New York Times Diversity and Inclusion Report, 2023). Similarly, although girls and women outperform boys and men in education (Voyer & Voyer, 2014), girls and women were long excluded from education and higher education (and in some places, they still are). In the United States, women were vastly outnumbered in all ranks of higher education through most of the 20th century but began earning most Bachelor’s degrees by 1983, most PhDs by 2006, and most faculty positions by 2019 (National Center for Education Statistics, 2021, 2023a). Women are still underrepresented among college and university presidents, but their numbers have grown from 10% in 1986 to 33% in 2022 (Schaeffer, 2023).

Institutions were designed primarily by men, for men, and historically were dominated almost entirely by men. This means that the structure and culture of institutions, the status quo norms and policies, reflect the values, priorities, and operational modes of men. Indeed, most institutions, from governments, universities, militaries, and corporations, operate as competitive hierarchies where employees work to prove their merit and gain status to earn a disproportionate share of resources and influence over others. In war, sports, and economies, coalitions clash for dominance, status, and resources. Even academia, a relatively peaceful institution, involves a competitive hierarchy both within and between universities, where students, faculty, and schools are evaluated on performance and ranked and sorted into lower and higher status groups and positions.

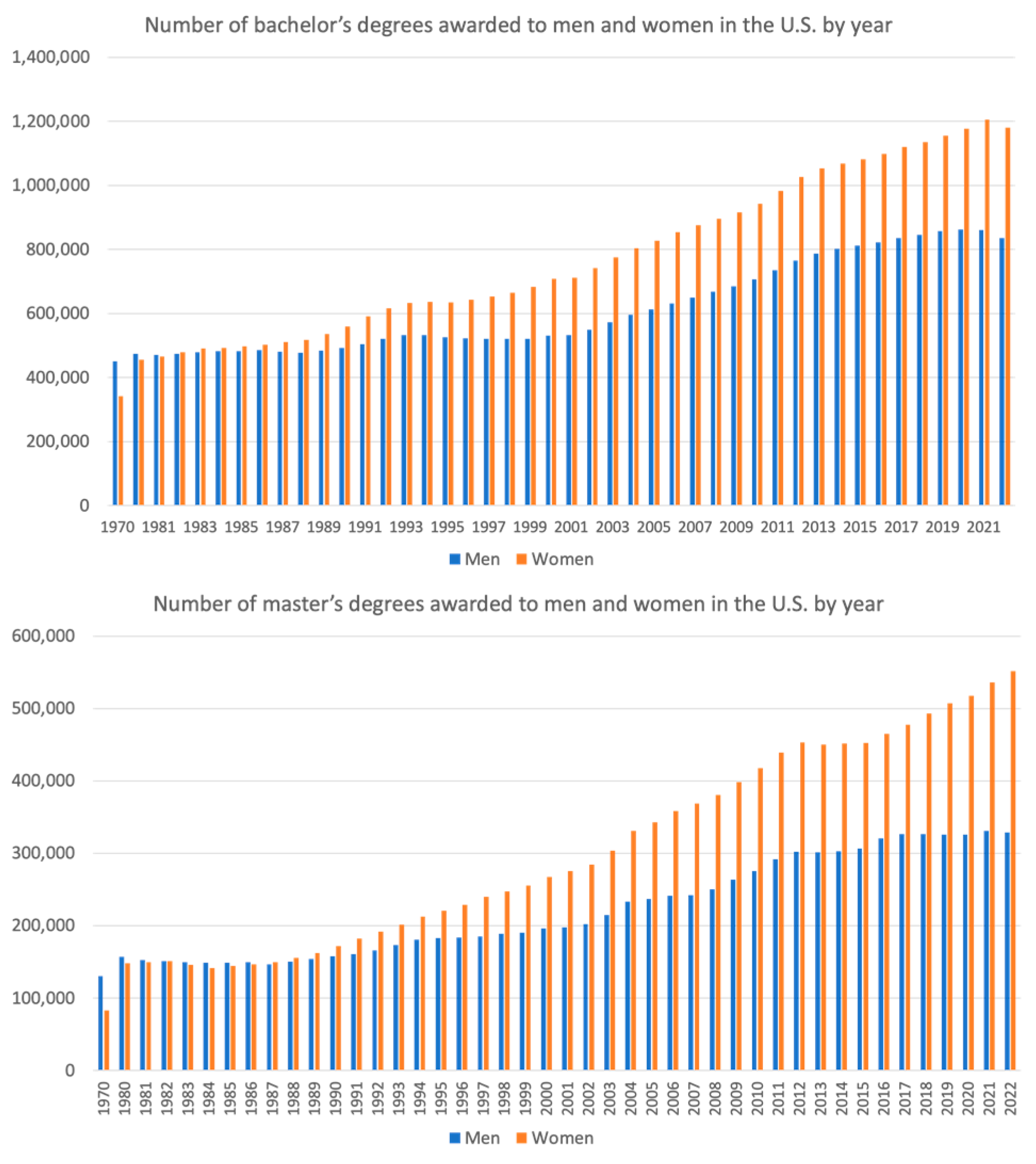

In recent years and decades, the demographic compositions of institutions have been changing – in some cases rapidly – as women have been empowered to participate in culture. Although women have made progress across diverse institutions, few institutions have undergone as dramatic a shift as academia. Among bachelor’s and master’s degree recipients, men are now as underrepresented as women were in the 1960s; among PhD recipients, men are now as underrepresented as women were around 1997; and even postsecondary faculty tipped over to majority female around 2019 (National Center for Education Statistics, 2023a, 2023b; see Figure 1). Given that men and women have somewhat different priorities on average, it would be surprising if this demographic shift had no noticeable impact on academic culture. And many cultural changes in academia reflect precisely what one would expect as female-oriented values rise to influence.

Figure 1.

Shifting sex composition at various tiers of academia.

3. Three Themes of Cultural Change

Although the ascendancy of women likely has had widespread and diverse consequences across institutions, I focus here on three changes that are particularly visible in academia:

- Increased preference for equity over merit-based hierarchy

- Increased prioritization of harm-avoidance over academic freedom and pursuit of truth

- Increased ostracism in response to conflict (think “cancel culture”)

Table 1 summarizes survey data from men and women (mostly from the U.S. but also the UK and Canada) regarding their beliefs about and preferences for higher education and academia. Summarizing across these various samples, there is clear and consistent evidence that women, compared to men, espouse views aimed at advancing agendas for equity, harm avoidance, and ostracism.

Table 1.

Self-report survey data demonstrating sex differences in support for equity, harm avoidance, and ostracism within the context of higher education.

Table 1.

Self-report survey data demonstrating sex differences in support for equity, harm avoidance, and ostracism within the context of higher education.

| Reference | Sample | Unit | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Info: | Clark et al. (2024) | 470 U.S. Psychology professors | % selecting "truth" | ||

| Item: | If pursuit of truth and social equity goals appear to come into conflict, which should scientists prioritize? | 66.4 | 43.0 | ||

| Study Info: | Clark et al. (2024) | 470 U.S. Psychology professors | % within sex giving response | ||

| Items: | How certain should harm be to suppress science? | ||||

| We should never suppress | 48.3 | 30.5 | |||

| Evidence that suppression only way to avoid harm | 27.8 | 43.3 | |||

| Clear evidence of harm | 17.8 | 18.3 | |||

| Suggestive evidence of harm | 0.4 | 3.7 | |||

| Harm should seem likely | 4.3 | 4.3 | |||

| Harm should seem possible | 1.3 | 0.0 | |||

| Study Info: | Clark et al. (2024) | 470 U.S. Psychology professors | % selecting "yes" | ||

| Item: | Should scholars be completely free to pursue research questions without fear of institutional punishment for their conclusions? | 60.5 | 39.8 | ||

| Study Info: | Clark et al. (2024) | 470 U.S. Psychology professors | Mean on a 0 to 100 scale | ||

| Items: | Support for retracting papers for… | ||||

| Data fraud | 99.7 | 99.7 | |||

| Analytic errors | 91.0 | 92.0 | |||

| Failures to replicate | 34.1 | 40.7 | |||

| Evidence of p-hacking | 66.5 | 69.7 | |||

| Failure to obtain ethics approval | 76.2 | 87.0 | |||

| Conclusions could harm vulnerable | 24.1 | 37.9 | |||

| Extremists misconstruing and weaponizing results | 19.4 | 26.7 | |||

| Desires to discourage research into… | |||||

| Evolved sexually coercive behavior | 12.7 | 24.9 | |||

| Gender bias not explaining STEM disparities | 6.6 | 11.4 | |||

| Racial bias in academia | 5.4 | 6.1 | |||

| Binary biological sex | 6.6 | 11.2 | |||

| Discrimination against conservatives in academia | 4.0 | 9.0 | |||

| Racial bias not explaining crime disparities | 5.3 | 10.7 | |||

| Evolved psychological sex differences | 5.6 | 12.0 | |||

| Genetic contribution to IQ race differences | 16.0 | 29.7 | |||

| Socially influenced transgender identity | 8.1 | 14.6 | |||

| Diversity causing worse work performance | 6.9 | 11.3 | |||

| Admiration toward retraction petitioners for… | |||||

| Data fraud | 70.7 | 72.9 | |||

| Error | 45.8 | 44.3 | |||

| Moral concerns about conclusions (e.g., reinforcing stereotypes) | 21.4 | 32.5 | |||

| Support for firing scholars for… | |||||

| Data fraud | 94.9 | 96.6 | |||

| Failures to replicate | 17.2 | 21.0 | |||

| Evidence of p-hacking | 43.2 | 53.1 | |||

| Sex with students | 71.1 | 81.2 | |||

| Moral concerns about implications of research conclusions | 11.9 | 18.0 | |||

| Research popular with extremists | 9.0 | 11.8 | |||

| Support for actions against scholars who report biological group differences | |||||

| Normal scientific criticism | 92.2 | 93.7 | |||

| Socially ostracizing them | 11.3 | 21.3 | |||

| Publicly labeling them pejorative terms (e.g., bigot, racist, sexist) | 8.5 | 12.4 | |||

| Disinviting them from talks | 18.2 | 28.8 | |||

| Refusing to publish their work regardless of its merits | 9.0 | 16.1 | |||

| Not hiring or promoting them even if they meet typical standards | 12.4 | 18.1 | |||

| Stigmatizing their graduate students and co-authors | 4.6 | 6.5 | |||

| Firing them | 4.7 | 8.9 | |||

| Shaming them on social media | 8.8 | 14.1 | |||

| Removing them from leadership positions | 19.7 | 33.6 | |||

| Study Info: | College Pulse (2019) | 4407 U.S. undergrads | % agreement | ||

| Items: | It is acceptable to shout down speakers | 42 | 58 | ||

| Inclusive society is more important than free speech | 28 | 59 | |||

| People need to be more careful about their language | 25 | 48 | |||

| Hate speech should not be protected by First Amendment | 26 | 53 | |||

| Violence is unacceptable for protest | 83 | 83 | |||

| Study Info: | Ekins (2017) | 2300 U.S. adults (weighted) | % support or agreement | ||

| Items: | The government should prohibit hate speech | 32 | 48 | ||

| Making it illegal to say offensive or insulting things about: | |||||

| African Americans | 36 | 57 | |||

| Immigrants | 33 | 46 | |||

| Gay, lesbian, transgender people | 27 | 45 | |||

| The police | 28 | 45 | |||

| Hispanic people | 30 | 45 | |||

| Muslims | 30 | 44 | |||

| Jews | 35 | 45 | |||

| Christians | 27 | 43 | |||

| Making it illegal to make sexually explicit statements in public | 36 | 54 | |||

| Making it illegal to burn the American flag | 50 | 65 | |||

| Hate speech is violence | 43 | 63 | |||

| Supporting the right to speak is the same as endorsing its content | 35 | 51 | |||

| Colleges should protect students from offensive ideas | 44 | 64 | |||

| Colleges should cancel speakers if students threaten violent protest | 49 | 67 | |||

| Confidential reporting systems to report offensive comments | 41 | 54 | |||

| Controversial news stories in student papers need approval | 37 | 51 | |||

| Speakers allowed to speak at college… | |||||

| ...plans to reveal names of illegal immigrants | 43 | 22 | |||

| ...says Holocaust did not occur | 54 | 28 | |||

| ...says all illegal immigrants should be deported | 71 | 43 | |||

| ...advocates conversion therapy | 60 | 35 | |||

| ...says transgender people have a mental disorder | 61 | 34 | |||

| ...says police are justified stopping African Americans at higher rates | 62 | 37 | |||

| ...criticizes the police | 62 | 37 | |||

| ...advocates violent protests | 23 | 11 | |||

| ...says all white people are racist | 59 | 37 | |||

| ...says whites and Asians have higher IQ | 62 | 38 | |||

| ...says men are better at math | 67 | 48 | |||

| ...says Christians are backwards | 62 | 36 | |||

| ...says Muslims shouldn’t be allowed to come to U.S. | 61 | 36 | |||

| Study Info: | Geher et al. (2020) | 140 U.S. Faculty | Points allocated (out of 100) | ||

| Items: | Academic freedom | 20.2 | 18.7 | ||

| Advancing knowledge | 28.3 | 25.2 | |||

| Academic rigor | 27.8 | 25 | |||

| Social justice | 11.4 | 15.9 | |||

| Emotional well-being | 10.6 | 15.1 | |||

| Study Info: | Kaufmann (2021) | 830 UK academics (YouGov) | % support for each response | ||

| Items: | An initiative requiring diversity quotas on reading lists: | ||||

| Publicly or privately oppose the initiative | 40.3 | 26.8 | |||

| Privately or publicly supporting the initiative | 24.7 | 39.6 | |||

| Response to open letter calling to fire colleague who reported research perceived as putting disadvantaged groups at risk: | |||||

| Sign or support open letter | 12.7 | 18.1 | |||

| Sign or support counter-petition to oppose firing | 29.6 | 18.7 | |||

| Study Info: | Kaufmann (2021) | 1076 US and Canadian academics | % support for each response | ||

| Items: | If you had to choose, which is more important: | ||||

| Inclusive course content | 24.6 | 61.5 | |||

| Intellectually foundational content | 53.3 | 32.8 | |||

| An initiative requiring diversity quotas on reading lists: | |||||

| Publicly or privately oppose the initiative | 46.6 | 21.3 | |||

| Privately or publicly supporting the initiative | 27.7 | 58.2 | |||

| Open letter calling to fire colleague who reported research | |||||

| perceived as putting disadvantaged groups at risk: | |||||

| Sign or support open letter | 9.5 | 22.4 | |||

| Sign or support counter-petition to oppose firing | 41.7 | 23.2 | |||

| Colleagues who refuse to alter reading lists for quotas: | |||||

| Take no action | 60.0 | 26.6 | |||

| Social pressure | 17.8 | 19.8 | |||

| Give undesirable admin duties or reduce research funding | 2.8 | 4.3 | |||

| Require implicit bias trainings | 10.3 | 23.2 | |||

| Cancel course | 3.1 | 6.6 | |||

| Fire employee | 0.6 | 2.1 | |||

| Priorities regarding tensions between academic freedom and social justice for disadvantaged groups | |||||

| Prioritize academic freedom | 71.7 | 41.8 | |||

| Prioritize social justice | 15.2 | 40.1 | |||

| Study Info: | Kaufmann (2021) | 169 UK PhD students | % support for each response | ||

| Items: | If you had to choose, which is more important: | ||||

| Inclusive course content | 32.1 | 53.2 | |||

| Intellectually foundational content | 60.7 | 40.3 | |||

| An initiative requiring diversity quotas on reading lists: | |||||

| Publicly or privately oppose the initiative | 28.6 | 21.1 | |||

| Privately or publicly supporting the initiative | 39.3 | 53.2 | |||

| Open letter calling to fire colleague who reported research perceived as putting disadvantaged groups at risk: | |||||

| Sign or support open letter | 23.2 | 30.2 | |||

| Sign or support counter-petition to oppose firing | 37.5 | 21.1 | |||

| Priorities regarding tensions between academic freedom and social justice for disadvantaged groups: | |||||

| Prioritize academic freedom | 46.6 | 32.1 | |||

| Prioritize social justice | 28.6 | 33.9 | |||

| Study Info: | Kaufmann | 334 US and Canadian PhD students | % support for each response | ||

| Items: | If you had to choose, which is more important: | ||||

| Inclusive course content | 34.2 | 67.3 | |||

| Intellectually foundational content | 61.7 | 28.5 | |||

| An initiative requiring diversity quotas on reading lists: | |||||

| Publicly or privately oppose the initiative | 26.7 | 7.0 | |||

| Privately or publicly supporting the initiative | 43.3 | 77.1 | |||

| Open letter calling to fire colleague who reported research perceived as putting disadvantaged groups at risk: | |||||

| Sign or support open letter | 27.5 | 49.1 | |||

| Sign or support counter-petition to oppose firing | 32.5 | 16.4 | |||

| Priorities regarding tensions between academic freedom and social justice for disadvantaged groups: | |||||

| Prioritize academic freedom | 47.5 | 26.6 | |||

| Prioritize social justice | 20.8 | 50.5 | |||

| Study Info: | Rausch et al. (2023) | 574 U.S. undergrad and grad students | Points allocated (out of 100) | ||

| Items: | Academic freedom | 18.1 | 14.8 | ||

| Advancing knowledge | 32.5 | 27.0 | |||

| Academic rigor | 19.5 | 16.8 | |||

| Social justice | 11.2 | 16.6 | |||

| Emotional well-being | 18.8 | 24.8 | |||

| Study Info: | Zhang et al. (2021) | 1193 abstracts (44% women first authors) | first author % representation within category | ||

| Items: | Publications aimed at scientific progress | 64 | 36 | ||

| Publications aimed at societal progress | 50 | 50 | |||

| Publications aimed at both | 45 | 55 | |||

| Study Info: | Zhang et al. (2021) | 2587 European | % indicating high | ||

| academics | importance | ||||

| Items: | Importance of each for motivating their research: | ||||

| Curiosity/scientific discovery/understanding the world | 95 | 96 | |||

| Application/practical aims/creating a better society | 62 | 70 | |||

| Inspiration from my colleagues (locally and/or internationally) | 54 | 61 | |||

| Contribute to the standing of my research unit/group | 50 | 52 | |||

| Progress in my career | 36 | 45 | |||

| This is what I do for a living/the job I am most competent for | 46 | 45 | |||

| Inspiration from students/young talents | 38 | 40 | |||

| Inspiration from users (outside science) | 21 | 32 | |||

| Study Info: | Zhang et al. (2021) | 2587 European academics | % selecting characteristic | ||

| Items: | Characteristics of the "best research: | ||||

| Has answered/solved key questions/challenges in the field | 75 | 74 | |||

| Has changed the way research is done in the field | 51 | 52 | |||

| Has been a centre of discussion in the research field | 35 | 39 | |||

| Has changed the key theoretical framework of the field | 38 | 36 | |||

| Has benefited society | 26 | 33 | |||

| Has enabled more reliable or precise research results | 25 | 29 | |||

| Was published in a journal with a high impact factor | 17 | 16 | |||

| Has attracted many citations | 17 | 16 | |||

| Has drawn much attention in the larger society | 14 | 15 | |||

| Is what all students/prospective researchers need to read | 9 | 9 | |||

Note. Across reports, many judgment calls had to be made regarding which groups, variables, and categories to include and how best to present the data. I did not always list the percentages for all available response options (such as "don’t know" or "no opinion"). For these reasons, not all response sets add up to 100%. Some items are paraphrased for space. And some data refer only to subgroups within the samples based on what was available. For a more comprehensive understanding of the surveys presented in this table, please refer to their source (i.e., the listed reference).

Equity > Merit. Compared to men, women prioritize equity and have heightened aversion to group differences (whether sex, race, or even religious) that could reveal inequities. Across studies, women are less inclined to prioritize truth above social equity (Clark et al., 2024); and are more inclined to prioritize social justice over academic freedom (Geher et al., 2020; Kaufmann, 2021; Rausch et al., 2023), diversity quotas and inclusive content above intellectually foundational texts (Kaufmann, 2021), and inclusive societies above free speech (College Pulse, 2019). Female psychology professors are more opposed to various kinds of research that might challenge assumptions of equality, including nondiscrimination explanations for sex differences in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) and race differences in crime rates, and the existence of psychological differences between men and women and of racial differences in intelligence (Clark et al., 2024). Women are also more punitive of colleagues who refuse to use diversity quotas in reading lists or who pursue biological explanations for group differences more generally (Clark et al., 2024; Kaufmann, 2021).

These self-reported differences in values, with women prioritizing equity and the protection and elevation of seemingly vulnerable groups, likely explain, at least in part, the introduction and then the colossal investment in diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs and requirements across virtually all areas and subareas of academia (e.g., Confessore, 2024; Paul & Maranto, 2021; Tiede, 2022). These programs simultaneously seek to promote or enforce equity while also providing special assistance to those perceived as vulnerable – two powerful motivations for women. For one example, the Society for Personality and Social Psychology introduced a submission policy for their 2023 conference, requiring hopeful presenters to explain how their presentation would advance DEI, and anti-racism goals (Haidt, 2022), indicating that proposals would be evaluated not just for their merit, but also for their adherence to a female-oriented moral agenda. This policy decision was made under a board that was ~85% female (Clark & Winegard, 2022). Future archival research should systematically explore the relationship between the gender composition of leadership and decision-making panels and the promotion of various policies and practices aimed at advancing equity.

In addition to DEI policies, it seems likely that increasing percentages of female instructors in both K-12 and higher education partially explain grade inflation. Grade inflation in the United States has been a concern since at least the 1960s (e.g., Goldman, 1985), with average grade point averages (GPAs) across high schools and universities continuing to climb to the present day. The average high school GPA climbed from 2.68 out of 4 (roughly between a C+ and a B–) in 1990 to 3.39 (roughly between a B+ and an A–) in 2021 (Sanchez & Moore, 2022), and the median undergraduate GPA reached 3.28 in 2020 (National Center for Education Statistics, 2020). At the same time, performance on standardized tests and assessments of educational progress has, if anything, declined (Aldric, 2024; Sanchez & Moore, 2022), suggesting that the impressive GPAs of recent cohorts reflect lenient grading more than educational or intellectual achievement. And some research indeed suggests that female educators give higher grades than male educators. A study of 3446 Israeli students (Grades 5 through 11) from 110 schools explored various predictors of student evaluations and found female teacher gender to be the strongest predictor of higher grades (Klein, 2004). Female teachers also gave students higher behavioral evaluations across six domains (e.g., diligence, extracurricular social behavior, and even cleanliness). And standard deviations were tighter among female teachers, seemingly because they clustered their evaluations toward the top of the scale. Similarly, in a study of over 24,000 teacher–student pairs of 7th to 9th graders in China, female teachers gave higher grades to individual students and to entire classes, patterns which persisted within disciplines, suggesting that differential grades were not the result of men and women teaching different disciplines (Cheng & Kong, 2023). Moreover, students of female teachers did not improve more or perform better on standardized cognitive tests. It thus seems unlikely that women were better teachers and more likely that they simply awarded higher grades. Similar patterns have been replicated among professors and university students at different institutions in the U.S. (Bailey et al., 2020; Jewell & McPherson, 2012). Just as young girls are inclined to distribute stickers more equally (Benenson et al., 2019), adult female educators might be inclined to distribute high grades more equally. If so, this could explain why grades in both K-12 and higher education continue to climb as women make up larger shares of instructors.

Harm avoidance > Truth, academic freedom. Prioritization of harm avoidance is reflected in women’s lower thresholds for suppressing scholarship for harm concerns, their prioritization of protecting students from upsetting ideas, and their greater willingness to silence and punish peers who forward potentially harmful ideas. Across studies, men are more likely to support academic freedom and reject the notion that scholarship should be suppressed if it has potential to cause harm, whereas women are more willing to negotiate these priorities (Clark et al., 2024; Kaufmann, 2021). Women are more supportive of retracting scholarly papers on the basis that they could harm vulnerable groups, have more admiration toward peers who petition to retract papers for moral reasons, and are more supportive of firing peers who forward morally undesirable empirical conclusions (Clark et al., 2024; Kaufmann, 2021). Women are more in favor of banning hate speech (College Pulse, 2019; Ekins, 2017) and of making virtually all manner of offensive speech illegal, including offensive or insulting comments about African Americans, immigrants, gay people, Hispanic people, Muslims, Jews, Christians, and even police (Ekins, 2017).

Emily Ekins (2017) documented wide-ranging sex differences in prioritization of eliminating risky statements vs. free speech. Women are more supportive of making it illegal to burn the American flag or make sexually explicit statements in public, canceling speakers if students threaten violent protest, enacting confidential reporting systems for reporting offensive comments, and requiring student papers to get approval before publishing controversial news stories. From holocaust denial to claiming transgender people have a mental disorder to criticizing the police, women are more inclined to disallow any controversial speech on campus. Women more highly endorse claims that hate speech is violence. And women are more inclined to agree that supporting the right to speak is equivalent to endorsing its content. This appears to be a sort of “guilt by association” risk avoidance – if a person defends a morally suspect peer, they too are morally suspect.

Women’s heightened censoriousness (Clark, 2021) might be interpreted as a sign of authoritarianism. Although there may be some merit to that perspective (see, e.g., Brandt & Henry, 2012), much of this censoriousness appears to be prosocially motivated – rooted in genuine concern for protecting vulnerable others from potential harm, whether physical or psychological (Clark et al., 2023, 2024). Women are more supportive of protecting students from offensive ideas (Ekins, 2017), and female scholars place higher priority on supporting the emotional well-being of students (Geher et al., 2020; Rausch et al., 2023). Zhang et al. (2021) found that female scholars are relatively motivated by the pursuit of societal progress, rather than basic scientific progress, whereas the opposite holds for male scholars. Men pursue truth for the sake of understanding. For women, the value of science lies in its potential to help others. Consequently, scientific findings with potential to harm not only lack value but must be actively discouraged.

Just as with DEI policies, we can see the manifestation of these harm concerns in academic policy and procedural changes, such as (i) the protection of students with safe spaces and trigger warnings, (ii) lowering the threshold for what constitutes harm (Haslam, 2016), such as microaggressions and implicit biases (intrapsychic associations that may or may not increase the odds of harmful behavior), and (iii) easing the detection of harms with anonymous reporting systems and revamped codes of conduct and reporting guidelines. Similarly, the guideline “do no harm” has been added as a scientific criterion for publishing in top journals, not as an ethical guideline for the treatment of participants (the job of ethics committees and Institutional Review Boards), but regarding potential harms that could be caused by the publication (and thus public awareness) of research (Nature, 2022; Nature Human Behaviour, 2022). Papers may be rejected, retracted, removed, or amended if they pose risks of harms (e.g., if they could fuel hate speech, or could be used to undermine the dignity of a human group). Given that this harm is only potential, can occur only indirectly through readers of the scholarship (who are subject to state laws and penalties), and applies to risks of “hate speech,” this policy reflects the prioritization of even small and unlikely harms above academic freedom and pursuit of truth. Future research should systematically explore sex differences among editorial leadership and their treatment of potentially offensive papers, and especially those perceived as posing risks to vulnerable groups.

Ostracize. Women have stronger desires to punish, name call, publicly shame, ostracize, strip of prestige and power, and fire scholars who forward morally undesirable ideas. When asked whether scholars should be free to pursue research without fear of institutional punishment, most male psychology professors said “yes” and most female psychology professors said “it’s complicated” (Clark et al., 2024). Female psychology professors were more supportive of firing their peers for many reasons, including evidence of p-hacking (manipulating data), having sex with students, and moral concerns about their research conclusions. And female scholars were more supportive of almost all punishments toward a peer who reported a biological explanation for group differences, including ostracism, public shaming, deplatforming, and firing.

Women are more supportive of shouting down and canceling speakers (College Pulse, 2019; Ekins, 2017). And across four samples of academics, women were more likely than men to report that they would sign an open letter to fire a colleague who conducted research perceived as putting disadvantaged groups at risk, and men were more likely than women to report that they would sign a counterpetition opposing the firing (Kaufmann, 2021). To study these patterns more systematically, future research should explore the gender compositions of signatories of petitions and counterpetitions aimed at ousting or protecting peers who forward morally undesirable empirical conclusions.

These activities – deplatforming, public shaming, ostracism, and firing – are characteristic of so-called “cancel culture,” and they are also female-oriented strategies for dealing with morally undesirable people. Because men benefited from maintaining maximally large groups (so long as group members could still contribute), they may be more willing to penalize but then readmit offending group members. Women benefited from maintaining morally pure groups, and so they are more interested in permanently eliminating offenders from their social orbits. Although I am not aware of newly implemented policy that clearly supports ostracism, there is evidence of its rise in academia. Recent years have seen record numbers of scholars targeted for sanction because of their research or teaching, with many cases clearly reflecting concerns about protecting vulnerable groups (e.g., Clark et al., 2023; German & Stevens, 2021). The very concept of “cancel culture” in academia (da Silva, 2021; Hooven, 2023) has only gained traction in the past decade – with just 398 Google Scholar hits between 2015 and 2019, compared to 15,800 from 2020 to 2024 – reflecting a newly emerging or rapidly intensifying concern that alleged infractions are now met with total loss of social standing.

4. Limitations and Complications of the Academic Patterns

The surveys reviewed above are self-report. On the one hand, these data show that women proclaim to have these values and priorities themselves. To assert that women do not have these values and priorities would be to disregard their stated preferences. However, more compelling data would show that these self-reported differences are observable in actual behavior and outcomes – that female scholars do indeed behave according to their stated values and that female leaders and groups implement policies and procedures that align with their self-reported values. Future research should conduct archival work to explore how sex ratios of groups, institutions, and leadership relate to behavioral and policy outcomes. And ideally, future research would test causal relationships between shifting sex ratios and institutional changes.

The relationships discussed above are also vastly more complicated than sex alone. Within institutions, women tend to be more politically left-leaning and younger (because older generations of women were prohibited or discouraged from joining institutions), and left-leaning and younger people also tend to have views more similar to women. These confounds are difficult to disentangle. In my own work, I have controlled for age and ideology and continue to find effects of sex (Clark et al., 2024). And certain patterns break from straightforward ideological explanations, such as women also disallowing speakers who criticize police or who claim that all white people are racist. Another survey of over 50,000 college and university students found that male students were much more supportive of a pro-abortion speaker than women (Stevens, 2023). Women are not merely opposed to speech that threatens their progressive values, but more opposed to any kind of controversial speech – from the left or right.

Readers might also note that the hard swing to the left among young women is a relatively recent phenomenon. I do not contend that women display these characteristics because they are progressive (although that might be part of it). Modern progressivism might appeal to women in part because of its current strong emphasis on protecting marginalized groups and the policing of moral norms. Different ideologies and religions that emphasize feminine values will tend to attract women. As women align with particular ideologies, creeds, or social movements, those movements may shift further toward female priorities. At the same time, movements that become too extreme or produce demonstrably bad consequences tend to attract criticism and eventually recede, change, or fail. Observable cultural shifts arising from shifting sex ratios are always in flux and interacting with surrounding social forces, and sex compositions do not guarantee any particular outcome.

One might also point out that empathy and protection of the vulnerable seem at odds with ostracism. Social exclusion can cause a great deal of suffering. However, empathy for one target can fuel moral aggression toward another (Bloom, 2017). Awareness that women desire to protect “the vulnerable” tells us little about which people and groups will receive their concern, or who they will side with when two vulnerable groups have competing interests (e.g., transgender athletes or female athletes). Both ideological and other social trends influence which targets receive empathy and which are punished in the name of justice. More generally, shifting sex demographics are far from the only variable contributing to recent cultural changes. Many variables have complex relations with both the rise of women and the emergence of female priorities in culture. Affluence and technological advancements likely made it easier for women to pursue higher education and invest in meaningful careers, while perhaps also contributing to a “fragile” generation that has low tolerance for discomfort. There are likely many related contributors to recent cultural shifts (e.g., social media). I contend only that the ascendance of women is one likely contributor.

I also acknowledge the enthusiastic support and participation of many men in these cultural changes. Some of this is due to natural variation with some men having more feminine priorities. But given that men are particularly savvy at navigating status hierarchies, it also seems plausible that in environments where women set the rules for status attainment, men would adopt more female values. In other words, compared to older men, younger men may have more feminine values because those values now help men attain status in modern institutions that reward commitment to female priorities. Indeed, over the past 10 years, attaining status in academia has required a convincing (even if inauthentic) commitment to DEI. Consistent with the possibility that young men have relatively feminine values, in a study on campus censorship of controversial books, older men were the least censorious, younger women were the most censorious, and younger men and older women were moderately censorious (Clark et al., 2020), indicating that young men held values more similar to older cohorts of women than to older cohorts of men. This possibility warrants further study: Are modern men more feminine than older generations of men and in what ways?

5. Beyond Academia

The growing influence of women has likely contributed to countless changes over recent decades. Below, I briefly highlight four such changes that I hope will inspire further research.

The Pride boom? Although societal acceptance of homosexuality has increased over time, men have consistently remained more opposed to homosexuality and same-sex marriage than women (Pew, 2017). Because men evolved to form alliances with masculine men of high coalitional value (Winegard et al., 2014), men are particularly averse to effeminate gay men, who appear to lack the characteristics of formidable allies (Benenson, 2014; Winegard et al., 2016). It is not so much homosexuality that bothers men, but rather effeminacy. Women do not care whether their friends are formidable warrior types. On the contrary, gay men make excellent allies to women, because they (i) pose less of a competitive threat than peer women do, (ii) are stronger than peer women and so provide better security, and (iii) pose less of a sexual threat than straight men do. I thus suspect it is no coincidence that many early champions of the gay community were women who attained influence prior to the broader ascent of women, such as prominent actresses and singers. Nor is it likely a coincidence that the gay rights movement gained rapid traction during the same period when women made significant intellectual strides (e.g., in journalism, politics, and academia). Without this rise in women’s influence, it’s uncertain whether the gay rights movement would have achieved the same level of advocacy and success – or done so as swiftly.

Animal rights? Women care more about animals and are more opposed to various uses and abuses of animals, including animal consumption and testing (e.g., Eldridge & Gluck, 1996; Graça et al., 2018; Herzog, 2007; Phillips et al., 2010). Women are roughly twice as likely to be vegetarian or vegan (Modlinska et al., 2020) and constitute 70% or more of animal right activists (Gaarder, 2011). Whereas most men (58%) favor using animals in scientific research, most women (62%) oppose it (Strauss, 2018). Based on these differences, I expected that women’s growing influence would have contributed to substantial progress in animal rights. Recent cultural changes are partially (although not entirely) consistent with this expectation.

Some indicators demonstrate shifting public attitudes in favor of animals, with an increase in the percentage of Americans who report that animals should have equal rights as humans (from 25% in 2003 to 32% in 2015; Riffkin, 2015), and the percentage of Americans who consider it morally acceptable to medically test on animals appears near record lows (although still a slim majority, at 52%; Brenan, 2022). In 2015, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced it would no longer support biomedical research on chimpanzees (Collins, 2015). According to United States Department of Agriculture statistics, the number of animals used in research has decreased substantially since 1992 (from over 2 million to less than 800,000), but there are concerns about data transparency and whether certain animals that require reporting (e.g., dogs, cats, nonhuman primates, rabbits, and guinea pigs) have merely been replaced – and in even higher numbers – with those that do not require reporting (e.g., mice, rats, birds, and fish) (Speaking of Research, 2019). Similarly, although per capita pork and beef consumption in the U.S. has declined slightly since the late 1970s, those declines have been more than offset by rising consumption of poultry (Our World in Data, 2024). These patterns seem to indicate that any progress in the treatment of animals may be limited to cuddly mammals – perhaps those most likely to attract the sympathy of women because they bear the greatest similarity to human children. Overall, the success of the animal rights movement is much less clear than the success of the LGBT movement. Intense commercial interests in the exploitation of animals may have prevented more noticeable progress (whereas commercial interests, such as the wedding industry, align with legal same-sex marriage).

Mental health? Women seek more (Oliver et al., 2005; Mackenzie et al., 2006; Wendt & Shafer, 2016) and provide more mental health care. Although only 41.5% of psychiatrists are female (Association of American Medical Colleges, 2022), women make up 72% of practicing psychologists (American Psychological Association, 2023) and 77.1% of mental health counselors in the United States (Data USA, 2022). Women both offer and receive more social support on social networking sites (Tifferet, 2020). And because women evolved to aid the survival of preverbal infants, who signal their needs only through emotion expression, women are highly sensitive and responsive to signals of emotional distress in others (e.g., Lutzky & Knight, 1994; Neff & Karney, 2005) and are better at recognizing nonverbal displays of emotion, especially negative emotion (Thompson & Voyer, 2014). Women more rapidly and more accurately respond to infant facial expressions (Babchuk et al., 1985). And even among nonhuman primates, females are more sensitive, responsive, and empathic toward nonverbal expressions of distress (see Christov-Moore et al., 2014 for a review).

As female concerns have risen to prominence, so has public concern with various aspects of mental health. Concepts such as self-care, me-time, burnout, work/life balance, and mental health days, and the notion that everyone has “trauma” are now commonplace. Despite greater public support for mental and emotional care, mental health concerns are largely on the rise, particularly anxiety and depression (American Psychiatric Association, 2024; Goodwin et al., 2020; Terlizzi & Zablotsky, 2024; Witters, 2023). There are at least two reasons why the ascendancy of women would coincide with increasing rates of mental health issues, one involving increased detection of true positives and the other involving the incentivization of false (or at least questionable) positives.

Given that women are more responsive to and concerned about emotional and psychological distress, they are likely more inclined to provide and encourage support-seeking for such distress. People suffering with mental health issues may be more likely than ever to seek out mental health care, improving our ability as a society to detect, diagnose, and provide care for individuals suffering from mental health problems. At the same time, women’s empathy and sensitivity to psychological and emotional distress is likely more easily exploitable than men’s, and this exploitability might incentivize claims of debilitating distress. Record numbers of undergraduates are registering with disability services to receive various accommodations (e.g., extra time on exams, absences without penalties) and primarily for mental health or other psychological issues (Greenberg, 2022). If women are more inclined to provide accommodations for self-proclaimed distress, this might inadvertently incentivize such proclamations and lead to increased claims of distress – both real and exaggerated. Similar logic might also explain so-called “victimhood culture” and a “coddled generation.” If unverifiable claims of distress are increasingly rewarded with accommodations, we should expect more people to report that (and perhaps believe that) they have suffered and continue to suffer abnormal hardship. The rise of women may thus have contributed to increases in both the accurate detection of genuinely debilitating distress and the incentivization of exaggerated claims of debilitating distress.

Fall of competent but criminal men? The #MeToo movement was gendered from the start, with predominantly female victims calling out male perpetrators for sexual harassment and assault. But I suspect the gender issue runs deeper than that. As discussed above, women are more supportive of punishing, shaming, and ostracizing morally questionable people. The flip side of that pattern is that men are less supportive of punishing, shaming, and ostracizing morally questionable people. Because men are motivated to create large, competent coalitions, men may be especially inclined to “look the other way” when an effective leader misbehaves. If a coalition is benefiting from, say, a highly competent military general, politician, financier, football coach, film producer, music mogul, or media personality, yet that highly competent person is widely known to be engaging in unethical or illegal behavior, men may be more willing to maintain a culture of silence to support the success of the coalition. Women, on the other hand, might care less about the competence and effectiveness of leaders and care more about whether the members of their social and work environments are morally decent and trustworthy.

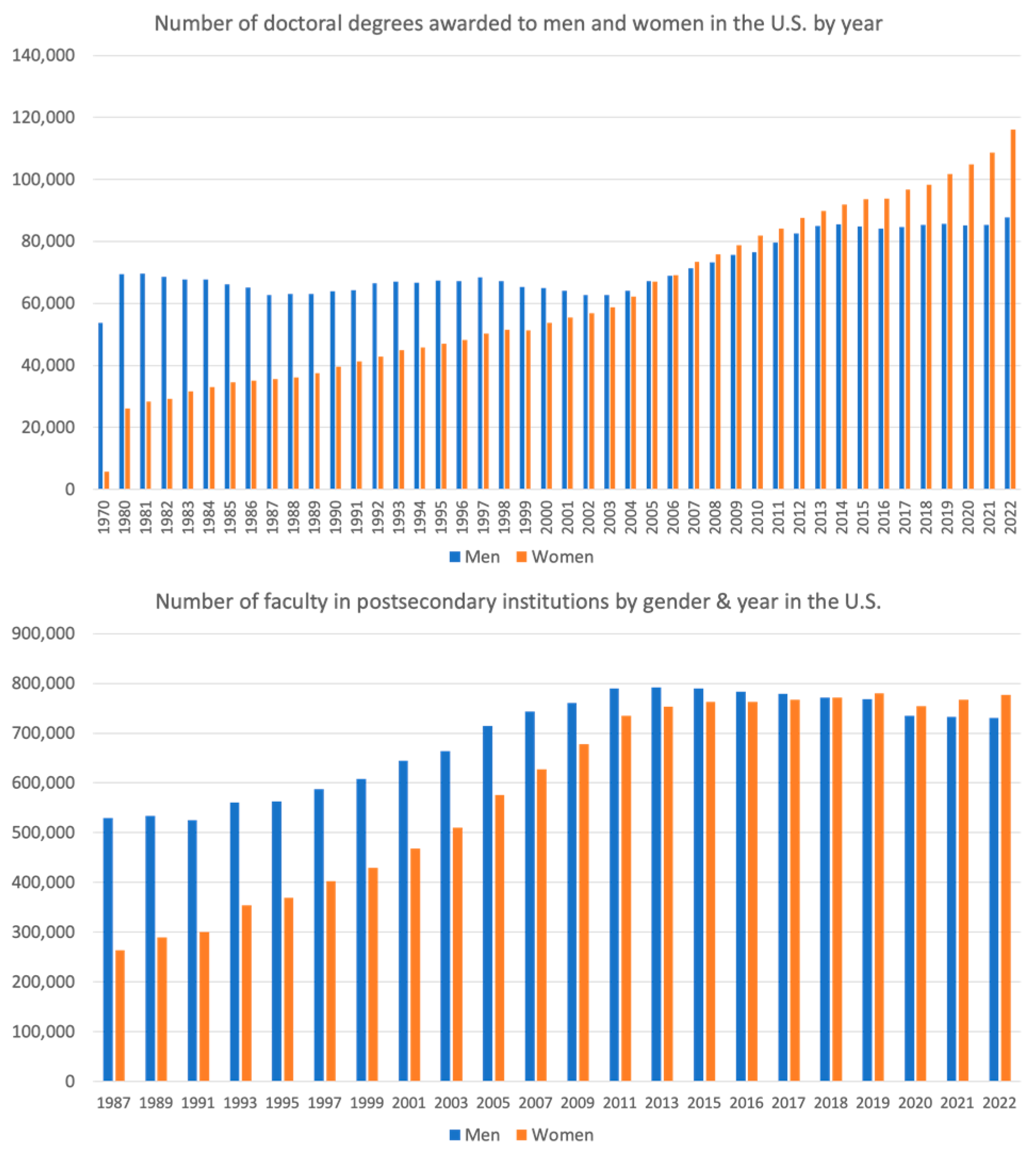

To test this possibility, I posted a few questions on CloudConnect (n = 500; Mage = 45.43; SDage = 15.83; 245 male, 250 female, 4 other or missing) asking participants to evaluate three statements about leaders on 7-point scales. As displayed in Figure 2 (with verbatim statements presented in the x-axes and response scales presented in the y-axes), men tended to agree more that (i) for a group to be successful, sometimes you need a leader willing to bend the rules, d = 0.25, p = .006 and (ii) it is ok to let a CEO keep working if accusations of unethical behavior are not easily verifiable, d = 0.44, p < .001. And men displayed a slight preference for a competent leader over a morally good leader, whereas women displayed slight preference for a morally good leader over a competent one, d = 0.34, p < .001. Future research should explore these patterns further, but they support my contention that men prioritize competent leaders and may be more willing to tolerate unethical or immoral behavior from a competent leader. Women, on the other hand, might be more inclined to report unethical leaders even if they are highly competent. However, given that women are also risk averse, I expect higher levels of reporting would take place through Human Resources complaints rather than through direct confrontations.

Figure 2.

Sex differences in attitudes toward leadership.

And many more? I expect similar shifts have emerged in nearly every domain where women have gained power, and I encourage relevant scholars to investigate whether comparable patterns exist in other areas, such as in corporations, the military, police departments, and the broader criminal justice system. I anticipate such changes will be largely absent in areas where gender representation has remained static and in countries and institutions where individuals have little influence over institutional and cultural norms.

6. A Non-Denialist, Non-Oppressive Response

Some readers may be inclined to deny the existence of sex differences in values and priorities for fear that these differences could be used to justify the oppression and exclusion of women from positions of power. This approach, however, does no favors to women by both ignoring women’s explicitly stated preferences and implying that women’s values are inherently problematic. On the contrary, women maintain the human species with their vigilance to danger and their drive to help vulnerable others. Humankind would not exist without women behaving as women do.

Other readers might conclude from these differences that women ought to be excluded from positions of influence. This, however, would deny institutions access to roughly half the talent pool and thus would undermine meritocracy and human progress. This perspective also drastically oversimplifies the relationship between female priorities and cultural outcomes. Men and women both have values and behavioral proclivities that can be constructive and destructive in different contexts. Men, with their tendencies toward conquest and sexual and physical violence, do not fit perfectly within modern institutions, and societies for millennia have paid enormous costs to tame aggressive male behavior. Cultures and institutions need to find ways of utilizing the positive aspects of male and female psychology while minimizing any antisocial or counterproductive aspects.

A constructive approach for managing the new cultural value-clash requires identification of recent changes, testing their costs and benefits and collecting relevant data, pursuing the maintenance of values and norms that produce positive outcomes, and challenging those that create costs with intellectual persuasion. By examining both the status quo norms and policies that were based on previously shared male values as well as the new norms and policies that have emerged from an increasingly female set of priorities, institutions could benefit from this period of turmoil in the long run. The policies and norms that can be justified with evidence as best advancing shared goals of scientific and human progress should (eventually) emerge victorious. To realize this optimistic outcome, we need only share a respect for and openness to empirical data. This project will be challenging, but in my view, holds the most promise for facilitating long-term human progress and (relative) social harmony.

7. From Worriers to Warriors for Justice

In institutions and in culture, the “worriers” of human evolution have become the warriors for social justice. As women have gained power and influence, policies and norms have shifted toward female priorities, with greater emphasis on harm aversion, stronger preference for equity above merit-based hierarchy, and the implementation of sweeping social exclusion as the response to morally suspect peers. The ascendancy of women has marked a period of incredible human progress and also of great conflict as a male-oriented status quo has clashed with rising female priorities. Many of the precise consequences of the ascendancy of women – perhaps including tolerance for same-sex relationships, more humane treatment of animals, and holding corrupt leaders accountable – will be celebrated. Some other consequences, such as “cancel culture” and threats to academic freedom, may be regarded as regrettable. Although these recent decades have been at times acrimonious, they provide an opportunity for reflection on which norms are worth defending and which need updating. Over time, through discovering what works and why, societies can benefit from the best aspects of both male and female psychology.

Funding

The work of Cory Clark was supported in part by the Templeton World Charity Foundation.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

| 1 | Some psychologists remain skeptical of evolved psychological sex differences (female psychologists more so than male psychologists [Clark et al., 2024]), and my argument does not really need the evolutionary claim – one can accept that differences exist without accepting any particular cause of them. Nonetheless, I find the evolutionary account the most plausible, illuminating, and generative explanation, and consider it useful for understanding why these differences exist and the important functions they serve. |

References

- Aldric, A. Average ACT Score for 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, and earlier years. PrepScholar. 2024. link to the article.

- American Psychiatric Association. American adults express increasing anxiousness in annual poll. 2024. link to the article.

- American Psychological Association. Demographics of the U.S. psychology workforce. 2023. link to the article.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Total physicians in psychiatry, 2022. 2022. link to the article.

- Babchuk, W. A.; Hames, R. B.; Thompson, R. A. Sex differences in the recognition of infant facial expressions of emotion: The primary caretaker hypothesis. Ethology and Sociobiology 1985, 6(2), 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, E. G.; Greenall, R. F.; Baek, D. M.; Morris, C.; Nelson, N.; Quirante, T. M.; Williams, K. R. Female in-class participation and performance increase with more female peers and/or a female instructor in life sciences courses. CBE – Life Sciences Education 2020, 19(3), ar30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benenson, J. F. Gender differences in social networks. The Journal of Early Adolescence 1990, 10(4), 472–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benenson, J. F. Greater preference among females than males for dyadic interaction in early childhood. Child Development 1993, 64(2), 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benenson, J. F. The development of human female competition: Allies and adversaries. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2013, 368(1631), 20130079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benenson, J. F. Warriors and worriers: The survival of the sexes; Markovits, H., Ed.; Oxford University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Benenson, J. F.; Apostoleris, N. H.; Parnass, J. Age and sex differences in dyadic and group interaction. Developmental Psychology 1997, 33(3), 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benenson, J. F.; Christakos, A. The greater fragility of females’ versus males’ closest same-sex friendships. Child Development 2003, 74(4), 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benenson, J. F.; Durosky, A.; Nguyen, J.; Crawford, A.; Gauthier, E.; Dubé, É. Gender differences in egalitarian behavior and attitudes in early childhood. Developmental Science 2019, 22(2), e12750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benenson, J. F.; Gauthier, E.; Markovits, H. Girls exhibit greater empathy than boys following a minor accident. Scientific Reports 2021, 11(1), 7965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benenson, J. F.; Hodgson, L.; Heath, S.; Welch, P. J. Human sexual differences in the use of social ostracism as a competitive tactic. International Journal of Primatology 2008, 29, 1019–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benenson, J. F.; Markovits, H.; Fitzgerald, C.; Geoffroy, D.; Flemming, J.; Kahlenberg, S. M.; Wrangham, R. W. Males’ greater tolerance of same-sex peers. Psychological Science 2009, 20(2), 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benenson, J. F.; Markovits, H.; Hultgren, B.; Nguyen, T.; Bullock, G.; Wrangham, R. Social exclusion: More important to human females than males. PLoS ONE 2013, 8(2), e55851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benenson, J. F.; Schinazi, J. Sex differences in reactions to outperforming same-sex friends. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 2004, 22(3), 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benenson, J. F.; White, M. M.; Pandiani, D. M.; Hillyer, L. J.; Kantor, S.; Markovits, H.; Wrangham, R. W. Competition elicits more physical affiliation between male than female friends. Scientific Reports 2018, 8(1), 8380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benenson, J. F.; Wrangham, R. W. Cross-cultural sex differences in post-conflict affiliation following sports matches. Current Biology 2016, 26(16), 2208–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, P. Against empathy: The case for rational compassion; Random House, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, M. J.; Henry, P. J. Gender inequality and gender differences in authoritarianism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2012, 38(10), 1301–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenan, M. Americans say birth control, divorce most ‘morally acceptable’. Gallup. 2022. link to the article.

- Buss, D. M. The evolution of human intrasexual competition: Tactics of mate attraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1988, 54(4), 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A. Staying alive: Evolution, culture, and women’s intrasexual aggression. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 1999, 22(2), 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Kong, D. Are female teachers more likely to practice grade inflation? Evidence from China. China Economic Review 2023, 80, 101987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christov-Moore, L.; Simpson, E. A.; Coudé, G.; Grigaityte, K.; Iacoboni, M.; Ferrari, P. F. Empathy: Gender effects in brain and behavior. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2014, 46, 604–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C. The gender gap in censorship support. Psychology Today. 2021. link to the article.

- Clark, C. J.; Fjeldmark, M.; Lu, L.; Baumeister, R. F.; Ceci, S.; Frey, K.; Tetlock, P. E. Taboos and self-censorship among US psychology professors. Perspectives on Psychological Science 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C. J.; Jussim, L.; Frey, K.; Stevens, S. T.; Al-Gharbi, M.; Aquino, K.; von Hippel, W. Prosocial motives underlie scientific censorship by scientists: A perspective and research agenda. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2023, 120(48), e2301642120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, C. J.; Winegard, B. M. Sex and the academy. Quillette. 2022. link to the article.

- Clark, C. J.; Winegard, B. M.; Farkas, D. A cross-cultural analysis of censorship on campuses, 2020; Unpublished manuscript.

- College Pulse. Free expression on college campuses; Knight Foundation, 2019; link to the article.

- Collins, F. NIH will no longer support biomedical research on chimpanzees; National Institutes of Health, 2015. link to the article.

- Confessore, N. The University of Michigan doubled down on DEI. What went wrong? The New York Times. 16 October 2024. link to the article.

- da Silva, J. A. T. How to shape academic freedom in the digital age? Are the retractions of opinionated papers a prelude to “cancel culture” in academia? Current Research in Behavioral Sciences 2021, 2, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data USA. Mental health counselors. 2022. link to the article.

- Ekins, E. The state of free speech and tolerance in America; Cato Institute, 2017; link to the article.

- Eldridge, J. J.; Gluck, J. P. Gender differences in attitudes toward animal research. Ethics & Behavior 1996, 6(3), 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaarder, E. Where the boys aren’t: The predominance of women in animal rights activism. Feminist Formations 2011, 23(2), 54–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geary, D. C. Male, female: The evolution of human sex differences, 3rd ed.; American Psychological Association, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Geher, G.; Jewell, O.; Holler, R.; Planke, J.; Betancourt, K.; Baroni, A.; Eisenberg, J. Politics and academic values in higher education: Just How Much Does Political Orientation Drive the Values of the Ivory Tower? Unpublished Manuscript. 2020.

- German, K.; Stevens, S. Scholars under fire: The targeting of scholars for constitutionally protected speech from 2015 to present. Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. 2021. link to the article.

- Goldman, L. The betrayal of the gatekeepers: Grade inflation. The Journal of General Education 1985, 37(2), 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, R. D.; Weinberger, A. H.; Kim, J. H.; Wu, M.; Galea, S. Trends in anxiety among adults in the United States, 2008–2018: Rapid increases among young adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2020, 130, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J.; Calheiros, M. M.; Oliveira, A.; Milfont, T. L. Why are women less likely to support animal exploitation than men? The mediating roles of social dominance orientation and empathy. Personality and Individual Differences 2018, 129, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, S. H. Accommodating mental health. Inside Higher Ed. 2022. link to the article.

- Haidt, J. The two fiduciary duties of professors; Heterodox Academy, 2022; link to the article.

- Haslam, N. Concept creep: Psychology’s expanding concepts of harm and pathology. Psychological Inquiry 2016, 27(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H. A. Gender differences in human–animal interactions: A review. Anthrozoös 2007, 20(1), 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooven, C. K. Academic freedom is social justice: Sex, gender, and cancel culture on campus. Archives of Sexual Behavior 2023, 52(1), 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jewell, R. T.; McPherson, M. A. Instructor-specific grade inflation: Incentives, gender, and ethnicity. Social Science Quarterly 2012, 93(1), 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, E. Academic freedom in crisis: Punishment, political discrimination, and self-censorship; Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology, 2021; link to the article.

- Klein, J. Who is most responsible for gender differences in scholastic achievements: Pupils or teachers? Educational Research 2004, 46(2), 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukianoff, G.; Haidt, J. The coddling of the American mind: How good intentions and bad ideas are setting up a generation for failure; Penguin, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lutzky, S. M.; Knight, B. G. Explaining gender differences in caregiver distress: The roles of emotional attentiveness and coping styles. Psychology and Aging 1994, 9(4), 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, C. S.; Gekoski, W. L.; Knox, V. J. Age, gender, and the underutilization of mental health services: The influence of help-seeking attitudes. Aging and Mental Health 2006, 10(6), 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modlinska, K.; Adamczyk, D.; Maison, D.; Pisula, W. Gender differences in attitudes to vegans/vegetarians and their food preferences, and their implications for promoting sustainable dietary patterns – A systematic review. Sustainability 2020, 12(16), 6292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Education Statistics. National Postsecondary Student Aid Study: 2020 undergraduate students; Institute of Education Sciences, 2020. link to the article.

- National Center for Education Statistics. Degrees conferred by postsecondary institutions, by level of degree and sex of student: Selected years, 1869–70 through 2030–31; Institute of Education Sciences, 2021. link to the article.

- National Center for Education Statistics. Number of faculty in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by employment status, sex, control, and level of institution: Selected years, fall 1970 through fall 2022; Institute of Education Sciences, 2023a. link to the article.

- National Center for Education Statistics. Degrees conferred by postsecondary institutions, by level of degree and sex of student: Selected years, 1869–70 through 2031–32; Institute of Education Sciences, 2023b. link to the article.

- Nature. Research must do no harm: New guidance addresses all studies relating to people. [Editorial] Nature. 14 June 2022. link to the article.

- Nature Human Behaviour. Science must respect the dignity and rights of all humans. Nature Human Behaviour 2022, 6, 1029–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, L. A.; Karney, B. R. Gender differences in social support: A question of skill or responsiveness? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2005, 88(1), 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New York Times. Diversity and inclusion report. The New York Times. 2023. link to the article.

- Oliver, M. I.; Pearson, N.; Coe, N.; Gunnell, D. Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: Cross-sectional study. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2005, 186(4), 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Our World in Data. Per capita meat consumption in the United States. Our World in Data. 2024. link to the article.

- Paul, J. D.; Maranto, R. Other than merit: The prevalence of diversity, equity, and inclusion statements in university hiring; American Enterprise Institute, 2021; link to the article.

- Pew. The partisan divide on political values grows even wider. Pew Research. 2017. link to the article.

- Phillips, C.; Izmirli, S.; Aldavood, J.; Alonso, M.; Choe, B. I.; Hanlon, A.; Rehn, T. An international comparison of female and male students’ attitudes to the use of animals. Animals 2010, 1(1), 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puts, D. A. Beauty and the beast: Mechanisms of sexual selection in humans. Evolution and Human Behavior 2010, 31(3), 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, Z. M.; Redden, C.; Geher, G. The value gap: How gender, generation, personality, and politics shape the values of American university students. Journal of Open Inquiry in the Behavioral Sciences 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, D.; Neumann, D. L.; Andrews, G. Gender differences in reading and writing achievement: Evidence from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). American Psychologist 2019, 74(4), 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riffkin, R. In U.S., more say animals should have same rights as people. Gallup. 2015. link to the article.

- Sanchez, E. I.; Moore, R. Grade inflation continues to grow in the past decade. ACT Research Report. 2022. link to the article.

- Schaeffer, K. The data on women leaders. In Pew; [Factsheet]; 27 September 2023; link to the article.

- Speaking of Research. US animal research statistics. Speaking of Research. 2019. link to the article.

- Stevens, S. T. 2024 College free speech rankings: What is the state of free speech on America’s college campuses? The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. 2023. link to the article.

- Strauss, M. Americans are divided over the use of animals in scientific research. Pew Research. 16 August 2018. link to the article.

- Svachula, A. When The Times kept female reporters upstairs. The New York Times. 20 September 2018. link to the article.

- Terlizzi, E. P.; Zablotsky, B. Symptoms of anxiety and depression among adults: United States, 2019 and 2022. In National Health Statistics Reports; 2024. link to the article. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A. E.; Voyer, D. Sex differences in the ability to recognise non-verbal displays of emotion: A meta-analysis. Cognition and Emotion 2014, 28(7), 1164–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiede, H. The 2022 AAUP survey of tenure practices. American Association of University Professors. 2022. link to the article.

- Tifferet, S. Gender differences in social support on social network sites: A meta-analysis. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2020, 23(4), 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyer, D.; Voyer, S. D. Gender differences in scholastic achievement: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 2014, 140(4), 1174–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, D.; Shafer, K. Gender and attitudes about mental health help seeking: Results from national data. Health & Social Work 2016, 41(1), e20–e28. [Google Scholar]

- Winegard, B.; Reynolds, T.; Baumeister, R. F.; Plant, E. A. The coalitional value theory of antigay bias. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences 2016, 10(4), 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winegard, B. M.; Winegard, B.; Geary, D. C. Eastwood’s brawn and Einstein’s brain: An evolutionary account of dominance, prestige, and precarious manhood. Review of General Psychology 2014, 18(1), 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witters, D. U.S. depression rates reach new highs. Gallup. 2023. link to the article.

- Young, C. Defining “Wokeness”. In The poisoning of the American mind; Jussim, L., Mackey, J. L., Eppard, L. M., Eds.; University of Virginia Press, 2024; pp. 210–217. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Sivertsen, G.; Du, H.; Huang, Y.; Glänzel, W. Gender differences in the aims and impacts of research. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 8861–8886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2025 Copyright by the author. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).