Controversial_Ideas , 5(2), 10; doi:10.63466/jci05020018

Article

U.S. Academics Have Freer Speech Than We Think

1

Department of Economics, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82071, USA

*

Corresponding author: matt.burgess@uwyo.edu

How to Cite: Burgess, M.G. U.S. Academics Have Freer Speech Than We Think. Controversial Ideas 2025, 5(Special Issue on Censorship in the Sciences), 10; doi: 10.63466/jci05020018.

Received: 6 April 2025 / Accepted: 3 October 2025 / Published: 27 October 2025

Abstract

:Academics in the United States face threats to their intellectual and expressive freedoms from both sides of the political spectrum. These threats are comparable to or greater than the threats of the McCarthy era, by some measures. However, far more academics self-censor than are censored by others. Although self-censorship may sometimes be rational from a careerist perspective, here I argue that academic self-censorship is often irrational. Theoretical and empirical evidence suggests that academic reward systems favor intellectual risk-taking in the long run, on average. In contrast, academics often avoid rational expressive risks due to fears of adverse non-careerist consequences and short-term incentives for risk avoidance. Personality traits correlated with risk aversion may be overrepresented among those who self-select into academia. Academics’ large-scale self-censorship behaviors create a free-rider problem and underappreciated risks to academia’s value proposition, its public trust, and, by extension, its funding and student enrollment. Self-censorship also makes free expression appear more transgressive, which may magnify both its real and perceived risks. Despite ongoing censorship threats, U.S. academia remains one of the expressively freest professions in the history of the world. Yet our freedoms are only useful – to ourselves and society – if we have the courage to use them.

Keywords:

censorship; self-censorship; free expression; cancel culture; courage1. Introduction

Academia in western countries has been facing real threats to academic freedom and free expression over the past ten years, the likes of which have not been seen for at least a generation (Lukianoff & Schlott, 2023). However, focusing on the United States, here I argue that self-censorship is a larger problem, and that many academics who self-censor may be overestimating the risks and underestimating the rewards to free inquiry and expression.

By several measures, threats to today’s academic and expressive freedoms are more severe than they were during the infamous McCarthy era of the 1950s, in which professors were fired for supporting communism. For example, Lukianoff and Schlott (2023) estimate that there were nearly 200 incidents, between 2014 and 2023, in which professors were fired for their speech or scholarship, compared to roughly 100 professors fired for allegedly supporting communism during the 1947–1957 period (Lazarsfeld & Thielens, 1958).

However, self-censorship is much more pervasive than censorship by authorities, and it, too, may be occurring on a larger scale than during the McCarthy era. For example, the 2024 Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) Faculty Survey Report (Honeycutt, 2024) found 35% faculty reporting that they toned down their written work for fear of causing controversy, compared to an estimated 9% in the mid-1950s. Although professional academics are my primary focus here, students may be self-censoring at even higher rates. For example, over 80% of Northwestern University and University of Michigan students in a 2023–2025 survey reported submitting coursework that misrepresented their views to align with what they perceived to be their professors’ views (Romm & Waldman, 2025).

Academics self-censor for a variety of reasons, the most obvious one being fear of being censored, losing their jobs, or other explicit professional or government sanctions. Academics also report self-censoring out of fear of subtler professional and social consequences such as social ostracism; losing out on speaking invitations, collaborations, and other networking opportunities; and losing stature within their academic communities (Honeycutt, 2024). In some fields – research on transgender issues being a well-documented example (Dreger, 2016; Singal, 2024) – researchers often face personal threats (including threats of violence) and harassment that may encourage others to self-censor or avoid the topic altogether. There are also more benign types of self-censorship, related to academics wanting to be civil or keep their speech focused on their expertise, for example.

Academics who self-censor may be overestimating the professional risks of speaking and researching freely. Academics – especially those with tenure or on the tenure track – have more legal and contractual protections than many realize. The arbitrariness of some instances of sanction relative to written policies understandably creates an unsettling sense of uncertainty. However, a close examination of FIRE’s (2025a) Scholars Under Fire database reveals clear patterns in risk factors for the most serious professional consequences for speech, such as loss of a job or immigration status. I argue that the vast majority of tenured and tenure-track faculty have none of these risk factors.

Moreover, academics who self-censor may be underestimating the professional rewards to honest, fearless research, public speaking, and to some extent teaching, on important but high-risk topics, especially those in their fields of study. Long-run incentives in academia reward risk-taking, originality, and rigorously challenging established paradigms. These incentives can be quantitatively described.

Irrespective of these individual-level rewards and risks, large-scale self-censorship poses a major threat to academic integrity, and, by extension, academia’s standing in society and funding. Academia’s value propositions to society lie in discovering and disseminating knowledge, and in educating the next generation of students and professionals. Self-censorship directly threatens these value propositions, and it thereby poses severe collective risks.

To put it bluntly: knowledge discovery and dissemination, and education, are public goods deserving of public funding; self-interested political posturing is not a public good, and it does not deserve public funding. If the public perceives that academics are corrupting their scholarship or teaching due to ideology or fear of ideological reprisals, academia will understandably lose public trust and support. Recent surveys (discussed in Section 6) suggest that academia is in fact losing public trust for these reasons and others. Lack of trust in academia has motivated Republican state and federal governments to decrease funding and/or increase oversight in academic institutions – actions that have often posed their own threats to expressive and academic freedoms (discussed in Section 2 and Section 3).

The collective risks that academic self-censorship poses create a free-rider problem. Honest speech and scholarship on difficult topics might carry concentrated professional risks to the academic in question, but they carry diffuse benefits to the academic enterprise. There is also a closely related prisoners’ dilemma problem. The more common it becomes for academics to exercise their expressive and academic freedom rights on difficult topics, the less transgressive such speech may appear to the would-be censors, and the smaller the risks such speech may consequently carry to the speakers.

If academics were more aware of the rewards to intellectual risk-taking and originality – which I argue are underappreciated – it would partly mitigate this free-rider problem. However, it would not mitigate the core positive externalities of free expression to institutional trust and other academics’ freedoms. Therefore, institutional and policy reforms are also needed to promote and reward intellectual courage, as I briefly discuss in Section 7.

The rest of the article is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the power centers of censorship. These power centers differ in important ways on the political left and right. Section 3 analyzes FIRE’s (2025a) Scholars Under FIRE database and describes the career-risk comorbidities that make scholars susceptible to career-threatening forms of sanction for speech (firing or job loss, loss of immigration status, etc.). It also describes some of the legal and policy protections academics have for their inquiry and expression. Section 4 describes the underappreciated rewards to free inquiry and expression. Section 5 examines the reasons academics self-censor in such high numbers, despite these rewards and protections. Section 6 examines the free-rider problem that self-censorship creates for academic institutions, and the prisoners’ dilemma problem that academics’ self-censorship creates for each other. Section 7 (briefly and non-exhaustively) discusses institutional reforms that could mitigate these problems and reduce self-censorship more generally. Section 8 offers concluding remarks.

2. Power Centers of Left- and Right-Wing Academic Censorship

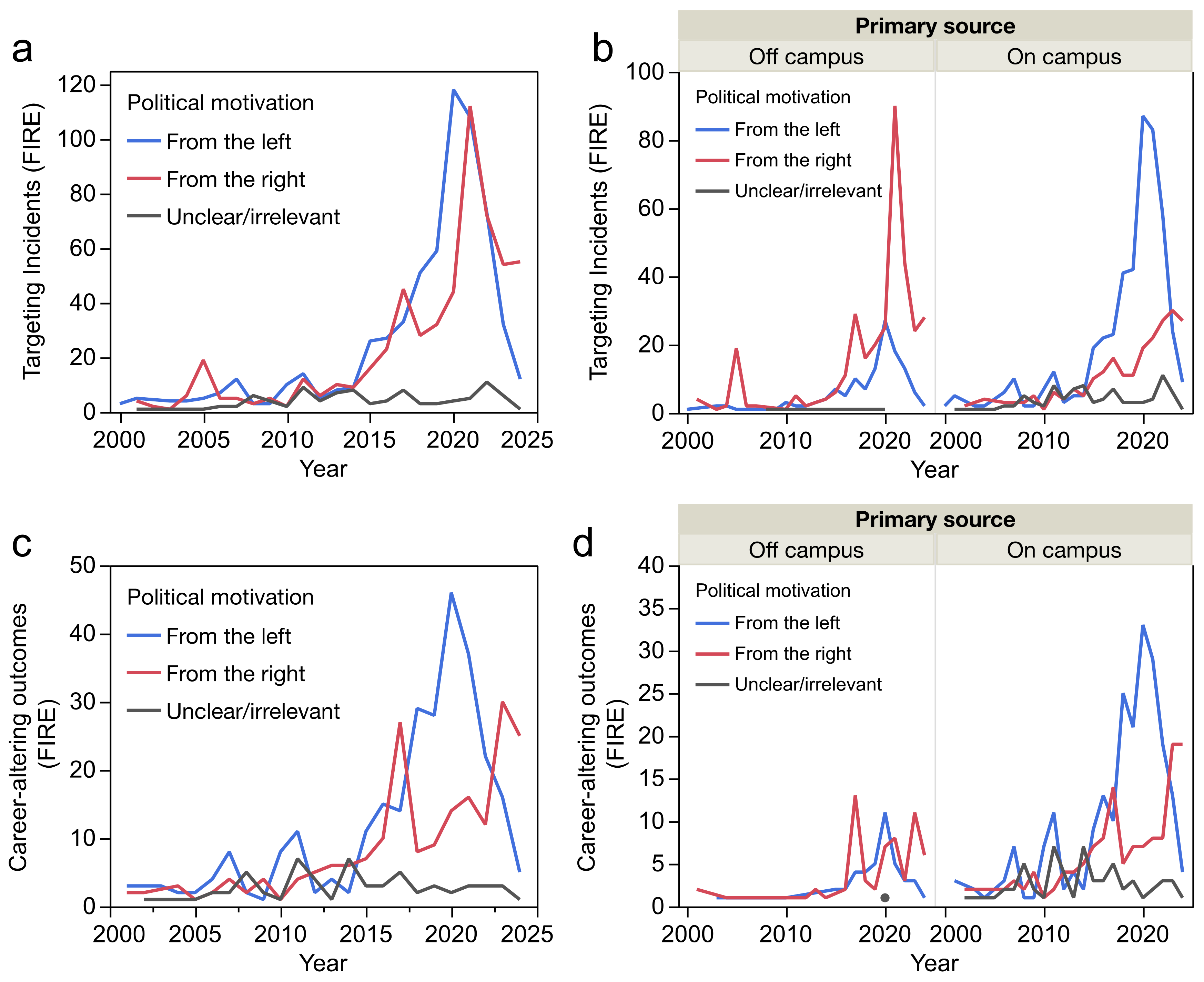

U.S. threats to academic freedom and free expression come from both sides of the political spectrum. For example, FIRE (2025a) has documented 1302 incidents of scholars being targeted for their speech since 2000 (as of March 2025). Of these, FIRE classifies 632 of these targeting incidents as coming from the political left, and 573 as coming from the political right. FIRE’s political classifications of individual incidents are of course somewhat subjective, but the aggregate patterns nonetheless contain useful information. The annual frequency of targeting incidents from both sides increased sharply during the late 2010s. Targeting incidents from the left peaked in 2020 (118); targeting incidents from the right peaked in 2021 (113) (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Targeting incidents from the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE)’s (2025a) Scholars Under Fire database, tabulated by year. Top panels (a,b) show all targeting incidents. Bottom panels (c,d) show incidents resulting in career-altering outcomes, defined here as one of: termination, resignation, demotion, or suspension. Left panels (a,c) tabulate incidents by political motivation. Right panels (b,d) tabulate incidents by political motivation and primary source of the targeting or complaint (on or off campus) (anonymously reported incidents are excluded). Incidents from 2025 are not shown.

Figure 1.

Targeting incidents from the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE)’s (2025a) Scholars Under Fire database, tabulated by year. Top panels (a,b) show all targeting incidents. Bottom panels (c,d) show incidents resulting in career-altering outcomes, defined here as one of: termination, resignation, demotion, or suspension. Left panels (a,c) tabulate incidents by political motivation. Right panels (b,d) tabulate incidents by political motivation and primary source of the targeting or complaint (on or off campus) (anonymously reported incidents are excluded). Incidents from 2025 are not shown.

Of the 1302 targeting incidents documented by FIRE, 539 resulted in what I characterize as a career-altering outcome, defined as a termination, resignation, demotion, or suspension. FIRE classifies 275 of these incidents as coming from the left, and 201 of these incidents as coming from the right (Figure 1c,d). Targeting incidents from the left resulting in career-altering outcomes sharply rose from 2015 to 2020 – peaking at 46 in 2020 – and sharply declined thereafter, with only five in 2024. Targeting incidents from the right resulting in career-altering outcomes had two peaks – one in 2017 (27), at the start of President Trump’s first term, and a second in 2023 (30) and 2024 (25) (possibly ongoing), following the 7 October 2023, terrorist attack on Israel, the ensuing war in Gaza and related unrest on college campuses, and President Trump’s second election.

The threats from each side of the political spectrum seem to manifest differently, for two reasons. First, academics and their administrators have political views which are far to the left of U.S. citizens, on average (e.g., Langbert, 2018; Abrams & Khalid, 2020). As a result, threats from the left to expressive and academic freedoms often – though not always – originate from on campus. Threats from the right often – though not always – originate from off campus (Figure 1b,d). Campus administrators may ultimately be instrumental in both types of censorship – they are usually the ones directly imposing sanctions on academics. However, the original complaint or request to censor more often comes from on campus when it comes from the left and from off campus when it comes from the right (FIRE, 2025a).

Second, the censorious factions of the left and right have different centers of power in American society. Conservatives tend to have more power in government, whereas liberals tend to have more power in institutions of knowledge and culture.

Conservatives tend to have more power in government because they are more numerous and more geographically spread out than liberals. For example, roughly 70% of Republicans self-identify as conservative or very conservative, while roughly 45% of Democrats self-identify as liberal or very liberal (Pew Research, 2024). More in Common’s (2018) Hidden Tribes report used polling data to identify the left and right “wings”, whose opinions separate themselves from the rest of the country; they estimated that 25% of Americans were part of the right wing, while only 8% of Americans were part of the left wing. As a result, left-wing ideas and candidates are often electorally weak, even in Democratic primaries, whereas right-wing ideas and candidates are difficult to beat in Republican primaries (Burgess, 2024a). Additionally, Republicans tend to control more state governments, because their base is more rural than the Democratic base. For example, as of January 2025, Republicans controlled 23 state governments, compared to 15 controlled by Democrats (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2025). (The others had split control.)

Liberals tend to have more power in institutions of knowledge and culture primarily because college-educated Americans are disproportionately liberal and Democrat (Grossmann & Hopkins, 2024). This divide is even larger among Americans with postgraduate degrees. For example, in a 2024 NBC News (2024) exit poll, 53% of voters with bachelors’ degrees were Democrats, compared to 59% of voters with postgraduate degrees and 36% of voters who did not attend college. Among professors, the Democrat-to-Republican ratio is even more lopsided, especially in social science (except economics) and humanities fields (Langbert, 2018; Abrams & Khalid, 2020). Indeed, pluralities of professors and majorities of graduate students in many of these fields self-identify as “radical”, “Marxist”, “activist”, or “socialist” (Jussim et al., 2023). The left-monoculture of many segments of academia, combined with these activist and censorious tendencies among a large minority, probably explain the pervasiveness of targeting incidents from the left emanating from on campus (Figure 1b,d).

These factors have also contributed to sharply declining trust in academia among Independents and Republicans since 2015, and the growing animosity towards academia among some Republican politicians. For example, a 2024 Gallup survey (Jones, 2024) found “political agendas” were the number one reason for low confidence in U.S. higher education. Vice-President J.D. Vance famously said “the professors are the enemy” during a speech in 2021 (Knott, 2024).

As a result of conservatives’ power in government and their distrust of academia, direct threats to free expression and academic freedom from government often come from the right. For example, 129 bills have been introduced in 29 states and the U.S. Congress, since 2023, which attempt to limit diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) activities (Chronicle of Higher Education, 2025), protecting academic freedom (e.g., from mandatory DEI statements) in some cases, but (not mutually exclusively) restricting academic freedom in other cases (e.g., FIRE, 2023). However, government threats to free expression and academic freedom also sometimes come from the left, and these can be more indirect or covert. For example, the Biden administration often required DEI components in federal research grants, and it pressured technology companies to censor scientific debate of its COVID-19 policies (e.g., Younes & Kheriaty, 2023; Efimov et al., 2024; U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, & Transportation, 2025). The next section explores the specific characteristics of academic targeting incidents resulting in career-altering outcomes.

3. Who Gets Canceled? Career-Risk Comorbidities

A close examination of recent cases of academic targeting resulting in career-altering outcomes provides insights into both key risk factors and key protections. I systematically examine cases of termination, resignation, demotion, or suspension from 2023 and 2024 in the FIRE (2025a) Scholars Under Fire database. I also discuss other high-profile cases of severe sanctions from the past few years, including 2025 cases of non-citizens being detained or losing their immigration status for reasons related to (or plausibly related to) their speech or scholarship.

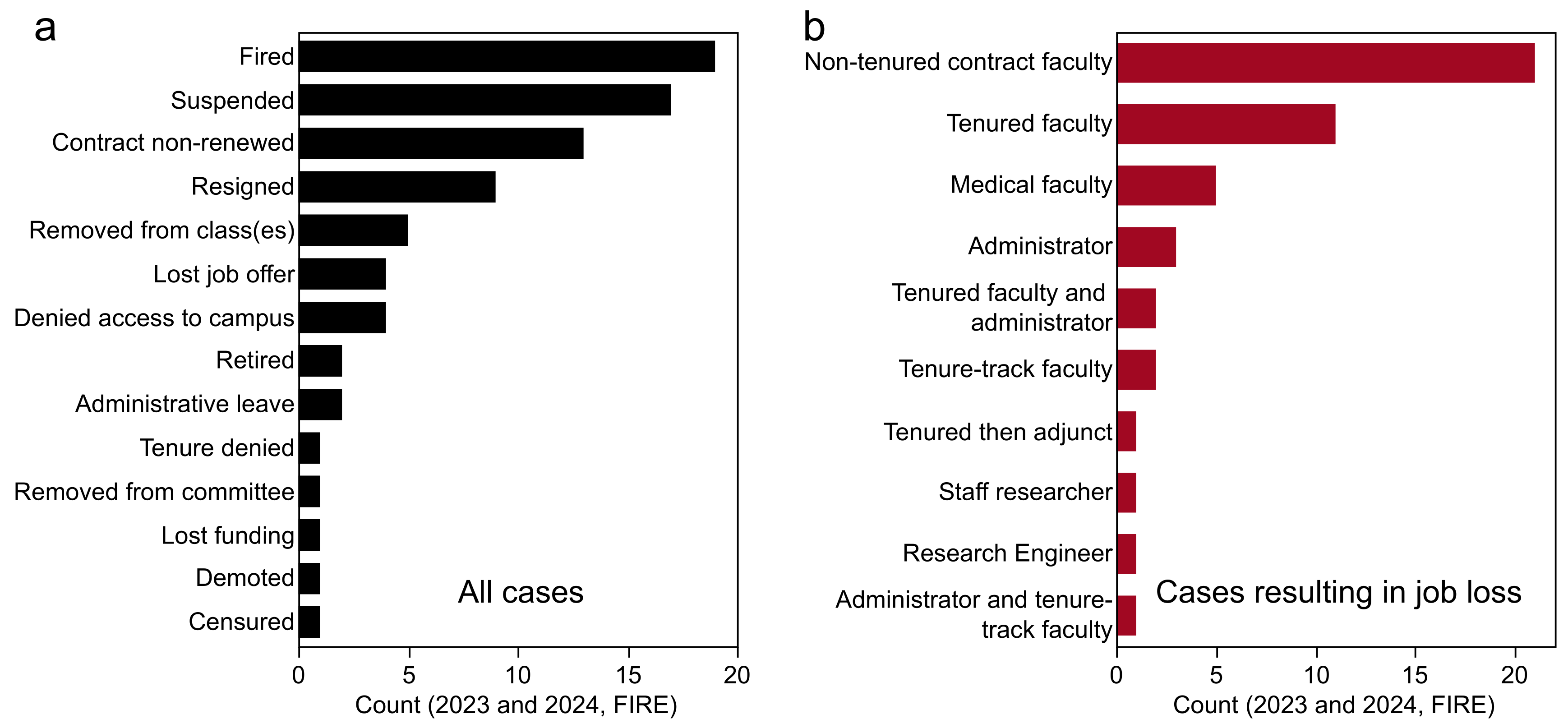

FIRE (2025a) documented 49 targeting incidents in 2023, 31 incidents in 2024, and one in 2025 (as of March) resulting in termination, resignation, demotion, or suspension. Of the 80 incidents in 2023 and 2024, 48 resulted in loss of a job – 19 scholars were fired; 13 had their contracts not renewed; 11 resigned or retired (some clearly under pressure, others less clearly so, and some only from administrative or outside jobs); four lost out on job offers or had them rescinded; and one was denied tenure (Figure 2a). In six of these cases, there is no public evidence that university attempted to sanction the employee, but the employee nonetheless left their position voluntarily due to tensions created by the incident. In one other case (of a rescinded job offer), the university reversed its initial adverse decision.

Among these 48 scholars who lost a job, the vast majority were not tenured or on a tenure track (Figure 2b). Thirteen were tenured and three were on the tenure track. The rest were contract or adjunct faculty (22), medical faculty (5; clinical medical faculty often do not have tenure), administrators (3), or research staff (2).

Of the three tenure-track faculty who lost a job, one (Logan Smith, Austin Peay State University) reportedly resigned under pressure after allegations surfaced that he attended the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville and engaged in other white supremacist activities. A second (Lara Sheehi, George Washington University) reportedly was accused of making antisemitic remarks in class. She was investigated by her university, but she was ultimately cleared of wrongdoing. She reportedly resigned to take a position at another university. The third (Tabia Lee) served as faculty director of De Anza College’s Office of Equity, Social Justice, and Multicultural Education, and she was reportedly denied tenure after a dispute over her criticism of DEI practices at the university (FIRE, 2025a).

Among the 13 tenured faculty who lost jobs, three were not reportedly sanctioned formally by their universities (but they resigned), and three others did not lose their current jobs, but lost out on job offers elsewhere. These scholars reportedly lost job offers for: advocacy in favor of DEI (Kathleen McElroy, Texas A&M), criticism of some DEI practices (Yoel Inbar, UCLA), and advocacy in favor of pro-Palestinian campus protesters (Nicole Nguyen, Dartmouth College) (FIRE, 2025a). It is worth examining the remaining seven cases – in which a tenured faculty member was reportedly fired (six cases) or retired under pressure (one case) – individually (FIRE, 2025a).

Figure 2.

Summary of scholars under fire (from the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, FIRE, 2025a, database) incidents from 2023 and 2024 resulting in career-altering outcomes. Panel a classifies all cases by sanction type. Panel b classifies cases resulting in job loss by the targeted scholar’s job type.

Figure 2.

Summary of scholars under fire (from the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, FIRE, 2025a, database) incidents from 2023 and 2024 resulting in career-altering outcomes. Panel a classifies all cases by sanction type. Panel b classifies cases resulting in job loss by the targeted scholar’s job type.

The terminations in two of these cases were not obviously related to constitutionally protected speech. In one case (Ann Bartow, University of New Hampshire), the university’s termination decision was upheld by an arbitration court, who ruled that there was a documented record of derelictions of academic duties meriting termination for cause (American Arbitration Association Arbitrator’s Findings & Award, 2024). In another case (Brian Salvatore, Louisiana State University), the scholar was fired over a long and complicated series of disputes with colleagues and the administration, many of which were personal in nature (e.g., accusing the chancellor of sexually harassing his wife – found by the school to be unsubstantiated – and allegedly showing a colleague pictures of the recently deceased body of another colleague) (Walters, 2024). Both scholars allege that their speech critical of their university administrations and (in Salvatore’s case) extramural political advocacy played a role in their dismissal (FIRE, 2025a).

A third case (Joe Gow, University of Wisconsin, La Crosse) relates to non-political speech. Here, the scholar was fired from an administrative position, and later from his tenured faculty position, for extramurally acting in adult films with his wife (FIRE, 2025a).

The remaining four cases plausibly relate to political speech, though the universities dispute this in some cases. James Bowley was reportedly fired from Millsaps College after he emailed his students, following the 2024 presidential election, to cancel his class, stating that he needed time to "mourn and process this racist fascist country” (FIRE, 2025a). FIRE has intervened on his behalf, citing lack of due process and arguing that his speech, even to his class, is protected under the First Amendment (Gluhanich, 2025). Amanda Stanford of Wingate University reportedly posted two comments on Facebook following the July 2024 assassination attempt against President Trump, stating, “I’m begging y’all to care like this when it’s a third grade (sic) classroom instead of an ear” and “How this kid missed is ridiculous” (FIRE, 2024). The university stated that she no longer worked there in response to a complaint. Scott Gerber of Ohio Northern University was fired – allegedly for “collegiality” – while he and his legal team contend that the university punished him for criticizing racial preferences in hiring and other DEI practices (Gerber v. Ohio Northern University et al., 2023). A court dismissed his lawsuit, granting a summary judgment in favor of the university (ibid). Katherine Franke retired from Columbia University, reportedly under pressure relating to her public statements about the Israel–Palestine conflict. She was specifically investigated by Columbia for stating, in a Democracy Now! interview that she had concerns about former Israeli soldiers attending Columbia because they “have been known to harass Palestinian and other students”. Columbia found these comments – as well as Franke’s decision to publicly name her complainants – to violate its Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action and retaliation policies (Quinn, 2025; Saul, 2025). The university was reportedly also facing public pressure from members of Congress to discipline Franke over these and other public statements she had made about the Israel–Palestine conflict (Quinn, 2025; Saul, 2025).

These cases documented in the Scholars Under Fire database (FIRE, 2025a) illustrate that it is quite rare for tenured and tenure-track faculty to lose their jobs over their speech, due to tenure protections, other protections in campus policies, and (at public universities) the First Amendment. These protections seem especially strong at large research universities.

The 2023 and 2024 cases examined above – along with other high-profile cases from previous years – also illustrate clear “career-risk comorbidities” that make scholars more susceptible to being materially sanctioned for their speech:

- Being an adjunct or at-will employee on a renewable contract. These scholars make up most cases involving job loss (Figure 2b).

- Being employed at a private school with explicitly strict limits on speech, such as a religious school. For example, five cases of non-tenured faculty being fired (or having contracts not renewed) for their speech in 2023 and 2024 involved religious schools in which the scholar’s speech violated the school’s religious norms.

- Being on the job market or between jobs. In the three of the above-described cases of faculty losing out on new positions for their speech, the speech in question did not (and likely could not have) cost them their current jobs. More broadly, it is much easier for universities and search committees to get away with not hiring someone for a legally or ethically dubious speech-related reason than it is to fire someone for a legally or ethically dubious speech-related reason, as firing decisions are more commonly scrutinized in court.

- Having a marginal tenure or promotion case. Similarly, it is much easier to vote against someone with a marginal tenure case for a legally or ethically dubious reason than it is to dubiously deny tenure to someone with a strong case and invite a lawsuit or bad publicity.

- Having actually violated a university policy, in addition to the speech offense. Several of the above-described cases illustrate this, as does the widely publicized case of classics professor Joshua Katz. Katz was fired from his tenured position at Princeton University in 2022, following a re-investigation of a sexual relationship he had had with an undergraduate student 15 years earlier, for which he had already been disciplined by the university. He claimed (plausibly) that the re-investigation was pretextual and related to his public criticism of DEI initiatives and Black Lives Matter protests (Hartocollis, 2022). However, his pretextual prosecution would not have been possible without the pretext – the relationship with his then-student.

- Being in a university or department at risk of closure or major funding cut. This situation makes it harder to protect a controversial academic, because protecting their job might put others’ jobs at risk. Columbia University’s recent actions may illustrate this. Would they have prosecuted scholars such as Katherine Franke under normal circumstances and not under the specter of Congressional investigations and funding risk?

- Having public views that – while being constitutionally protected in most cases – are extremely unpopular or taboo in society, not just in academia. As I outline in the next section, there can be major career benefits to articulating views that are broadly popular, but locally taboo in one’s institution. Doing so can lead to larger audiences and rewards, even if it causes one to leave their institution. Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson’s career powerfully illustrates this. Someone who is persecuted for articulating popular views can also sometimes rally a large outcry from their colleagues or the public in their defense, making their continued persecution riskier for the institution than allowing their expressive freedom. However, the opposite incentives apply to someone articulating broadly taboo and unpopular views, such as explicit sympathy for Hamas and the October 7, 2023, attack, referring to Zionist Jews as “Babylon swine”, or participating in white supremacist organizations, to name three real examples which ended in job loss in 2024 (FIRE, 2025a).

Non-citizen status is emerging as a new category of career-risk comorbidity under the second Trump administration. Several international graduate students and postdoctoral scholars, as well as a doctor and medical professor, have recently been deported or targeted for deportation. Some cases seem to involve stricter enforcement of existing visa and green card (permanent resident) regulations. For example, a German engineer with a green card was detained over years-old drug and driving-under-the-influence (DUI) charges, which have always been grounds for removal under U.S. law, but may have been inconsistently enforced under previous administrations (Lemon, 2025). A Lebanese medical professor had her H-1B visa revoked for allegedly attending Hezbollah (a U.S.-designated foreign terrorist organization (U.S. Department of State, 2025)) leader Hassan Nasrallah’s funeral (Rose & Pazmino, 2025). In other cases – all (to my knowledge) related to pro-Palestinian campus activism – domestic speech that would be constitutionally protected for a U.S. citizen is the only publicly known charge (FIRE, 2025b; Pazmino et al., 2025).

Scholars having these career-risk comorbidities deserve the same academic and expressive freedom rights as anyone else, of course. My point in highlighting them is not to suggest otherwise. Instead, my points are twofold. First, these patterns of career risk are relatively predictable and identifiable. This means that most scholars should be able to assess their risk, with the caveat that risks can change with changes in government, as the pro-Palestinian activism cases illustrate. Second, many scholars – including most tenured and tenure-track faculty at large universities – have none of these comorbidities, in addition to having strong protections from law and university policies. Such scholars therefore have freer expression than they might realize. In fact, I argue in the next section that there are often greater rewards than academics realize to speaking and researching (and to some extent teaching) freely, perhaps especially in areas that are broadly understood to be important but are understudied due to academic orthodoxies or political pressures.

4. Professional Rewards to Free Inquiry and Expression

Academia has the strange character of often attracting risk-avoiders to its ranks (discussed in the next section) and having short-run incentives for risk aversion, despite having clear long-run incentives for risk taking.

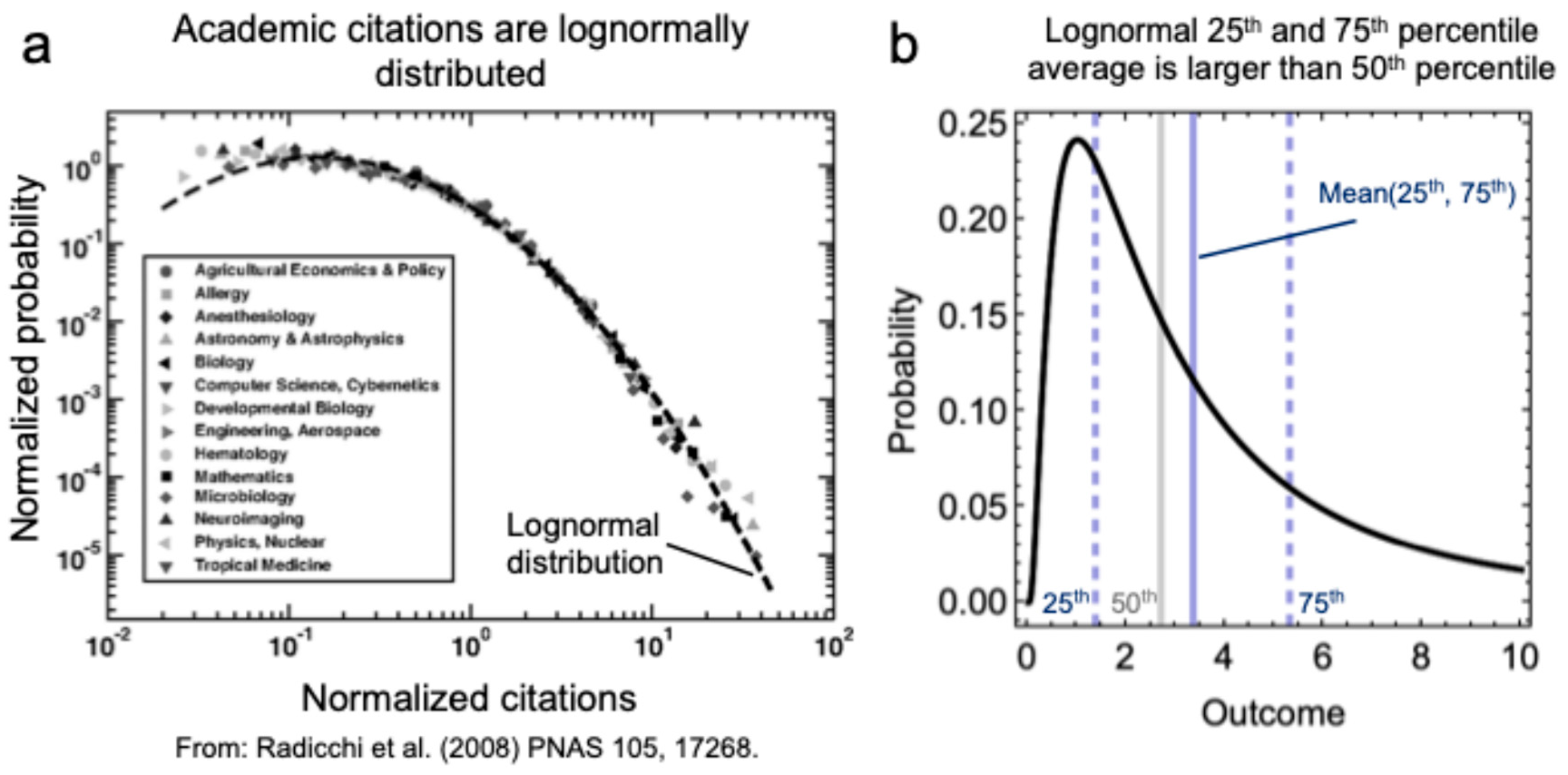

Statistically speaking, the impact and rewards of academic research have a heavily right-skewed distribution. This means that the upside risks are much larger than the downside risks, which means that risk-taking is rewarded, on average. For example, the distribution of citations in most fields is lognormal (Figure 3a). So, if one had a choice between writing a paper guaranteed to have the 50th percentile in citations or writing a paper with an equal chance of the 25th and 75th percentiles, the risky option would be the better choice. The average of the 75th and 25th percentiles is larger than the 50th percentile of a lognormal distribution (Figure 3b). The benefits to risk taking get larger further out in the right tail.

Figure 3.

Panel a shows normalized probability distributions of academic citations by discipline (points), compared to a lognormal distribution (dashed line). This panel is reproduced and adapted from Radicchi et al. (2008), Copyright (2008) National Academy of Sciences, as permitted by Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025) Rights and Permissions policy. Panel b shows a lognormal distribution of a hypothetical academic success outcome (e.g., citations), highlighting the fact that the average of the 75th and 25th percentiles is larger than the 50th percentile, due to the right-skewness of the lognormal distribution.

Figure 3.

Panel a shows normalized probability distributions of academic citations by discipline (points), compared to a lognormal distribution (dashed line). This panel is reproduced and adapted from Radicchi et al. (2008), Copyright (2008) National Academy of Sciences, as permitted by Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025) Rights and Permissions policy. Panel b shows a lognormal distribution of a hypothetical academic success outcome (e.g., citations), highlighting the fact that the average of the 75th and 25th percentiles is larger than the 50th percentile, due to the right-skewness of the lognormal distribution.

More broadly, scholarship is a “strong-link problem” (as described by psychologist Adam Mastroianni (2023)). Individual academic careers (perhaps especially those of top scholars), the progress of fields, and the influence of academic departments all tend to be driven by a small number of their most influential discoveries, papers, ideas, and scholars. This is why citation distributions (and other distributions of impact) have a thick right tail (Figure 3a). My PhD advisor in graduate school would describe this phenomenon by telling us (his students), “If you’re lucky, you’ll be known for one great idea by the end of your career.” In other words, having even one of those important ideas that shapes a field, throughout an entire career, would constitute a rarefied success which most scholars can only aspire to. Relatedly, a scholar is in rarefied air if they are remembered at the end of their career for even one important idea.

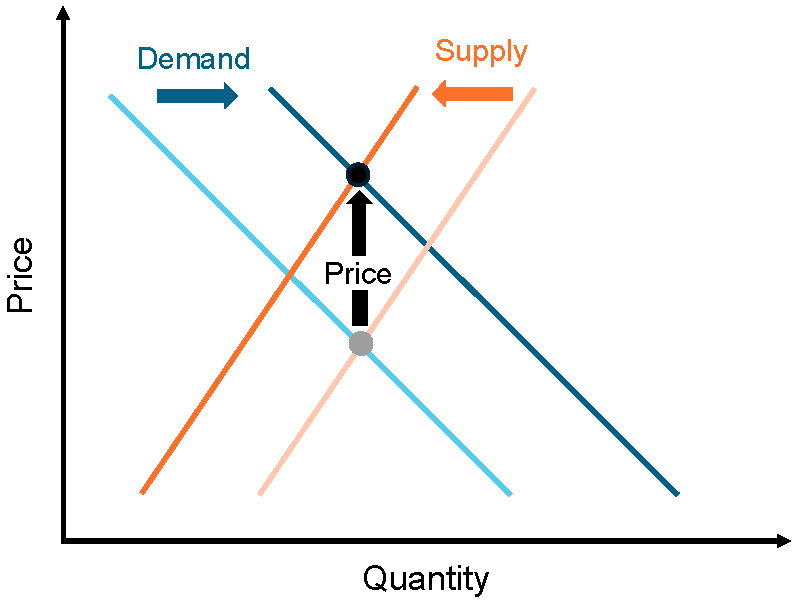

Where does one find these great ideas – the research questions that will define careers and, in some cases, fields? Physics Nobel laureate Steven Weinberg (2003) advised, in a famous commencement address: “go for the messes – that’s where the action is”. In other words, the questions that define fields and careers are ones that are not only important but are also understudied. This is basic economics: if demand for something is high and supply is low, society will pay a high price for it (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A simple supply-and-demand model illustrating how increasing demand and decreasing supply increases the market price.

Figure 4.

A simple supply-and-demand model illustrating how increasing demand and decreasing supply increases the market price.

If a question is important, why would people not be studying it already? There are many possible reasons. For example, some important questions require specialized knowledge or technical skills to answer, which few scholars have. Other important questions might require combining knowledge from disparate disciplines that few scholars can bridge. Others might be known to be so difficult as to be intractable on the timespan of an early career (at least).

However, fear is another common reason. It could be fear of straying from well-worn paths (in terms of topics, methods, etc.) of others in the field. It could be fear of challenging an established paradigm. (I tell my graduate students: If you want to do paradigm-shifting research, you will need the courage to break someone’s paradigm. That person will probably be powerful and upset.) It could also, of course, be fear of challenging a political taboo or causing controversy.

Summoning the courage to take an intellectual risk is not easy, but I would argue that it is often easier than learning a specialized technical skill or broad interdisciplinary knowledge. Therefore, if other scholars are too afraid to speak important truths or pursue important research questions, we should see this as a golden opportunity.

Whether or not one agrees with his views, Jordan Peterson’s career powerfully illustrates the benefits of exploring intellectual areas that are taboo within academia but demanded and undersupplied in broader society. Although Peterson faced backlash for his ideas from colleagues and eventually chose to leave academia as a result (Peterson, 2022), he has traded his old professorial career for a new one in which his books sell millions of copies (Penguin Random House, 2025) and he gives public talks in international stadium tours (Peterson, 2025). Other scholars who have generated large and lucrative followings for their work, helped at least in part by challenging academic orthodoxies of various types, include Jonathan Haidt, Gad Saad, Carole Hooven, Colin Wright, Adam Mastroianni, and Roger Pielke Jr., to name a few (non-exhaustive) examples. There are analogous examples in journalism, such as Bari Weiss and Matt Yglesias.

There are also many examples of scholars benefiting from taking intellectual risks, beyond subjects related to today’s political taboos. Biochemist Katalin Karikó spent her career researching messenger RNA (mRNA), and she was at many turns discouraged from doing so by some colleagues and her institution (University of Pennsylvania) (Kolata, 2023; Knox, 2023). However, her work ended up laying the foundation for the COVID-19 vaccines and earned her the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine. Economist John Maynard Keynes challenged mainstream free-market ideas – including those of his earlier mentors – to argue that government interventions to boost demand are important to recovering from recessions (Skidelsky, 2005). He is now widely considered to be one of the fathers of modern economics.

My own career has followed this pattern (on a much smaller scale) as well. For example, my two most-cited papers (currently) challenged a major paradigm regarding how emissions scenarios were used in climate change science (Burgess et al., 2021; Pielke et al., 2022). Careers of several colleagues in my field have followed analogous patterns.

Three potential objections to my argument here are worth discussing. First, my argument largely focuses on research, not teaching, nor extramural speech or activities unrelated to one’s research. These activities do seem somewhat riskier than research. Teaching is less public, less scripted, and more exposed to internal student complaints.1 Extramural speech, or activities unrelated to one’s professional responsibilities, are not protected by academic freedom, though they are protected by the First Amendment at public universities.

Nonetheless, there can be rewards to intellectual risks in these areas, too. The popularity and national acclaim of transgressive courses such as Ilana Redstone’s (2021) “Bigots and Snowflakes”, Simon Cullen’s (2021) “Dangerous Ideas in Science and Society”, Sam Richards’ (2019) “Race and Ethnic Relations”, and Terry Price’s (2025) “You Can’t Think That! Or Can You?” illustrate this. Extramural speech played a role in the successes of several public scholars mentioned above, including Jordan Peterson. My experience resonates with both points, too, again on a smaller scale.2,3

Second, my argument above does not address the professional risks to especially controversial research topics, such as research on potential links between race and biology, and/or biology’s relationship to measured group differences in socially desirable traits. These topics (along with a small number of others; see Dreger (2016) for examples) do seem genuinely riskier than some of the topics mentioned above. Indeed, several junior scholars, including Bo Winegard (see Flaherty, 2020), Noah Carl (see Adams, 2019), and Nathan Cofnas (see Somerville, 2024), have recently lost jobs for studying race and biology or variants of it. A recent survey found high levels of reported self-censorship among academic psychologists on this topic and others (Clark et al., 2024).

The properties that seem to make this topic especially professionally risky are its taboo in society (not just in progressive academia), and its lacking of publicly salient benefits from study. For example, research on costs of climate change policies or risks to medical gender transitions for minors speaks to widespread public concerns – costs of living and children’s welfare, respectively – despite these topics being controversial and violating progressive political taboos. In contrast, potential societal benefits from studying race and biology, if they exist, are not salient. Popular (with the public) and legal arguments against affirmative action do not depend on the results of this field of study, for example,4 despite what some scholars of this topic claim (e.g., Cofnas, 2022). In terms of the simple economics of Figure 4, this means that demand for research in this area, and consequently the price society is willing to pay for it, is likely low, not high. Of course, my explanation for the professional risks to studying extremely taboo topics, such as race and biology, does not invalidate the academic freedom rights of scholars of these topics on principle (as Cofnas’ colleagues argued in a recent open letter (Crisp et al., 2024)). However, it may explain why the rights of scholars of less controversial topics, which are more easily connected to the public interest, may be more easily protected in practice.

A third potential objection to my argument is that – given the influence of peer evaluation internal to the academy on the demand for specific lines of inquiry – my supply-and-demand model (Figure 4) might actually better motivate research in fashionable progressive areas such as social justice than it motivates research in more understudied, heterodox areas. This argument has clear short-term merit at certain times in history. For example, in the years immediately following George Floyd’s death in 2020, there was a surge in demand for social justice professors, but the supply of candidates for these positions was determined largely by decisions made years earlier (e.g., candidates’ decisions to study social justice topics in graduate school). Social justice scholars – perhaps especially those belonging to progressively favored demographic groups – therefore faced a highly favorable job market during those years.

However, I would hypothesize that internal academic demands can only sizably deviate from societal and popular demands – the ultimate sources of academia’s funding and support – for so long. Just as internal suppression of publicly demanded lines of inquiry can create lucrative opportunities outside of academia for heterodox scholars (illustrated by the examples mentioned above), internal inflation of lines of inquiry not demanded by the public can lead to dynamics analogous to asset bubbles in finance. The rapid rises, and then sudden collapses, of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing (Cutter & Glazer, 2024) and the corporate DEI industry (Goldberg et al., 2025) over the past decade illustrate this bubble-like dynamic in the business world. These cultural forces, combined with mounting federal and state government pressures against social justice research and DEI, may be creating similar downward pressures on demand in academia.

In summary, the trajectories of many scholars’ careers (perhaps especially those at the top), and the benefits of scholarship and academic institutions to society, tend to be disproportionately driven by a small number of the very best ideas and research questions. Taking intellectual risks increases the odds of uncovering these great ideas and research questions. This implies both that scholars often have careerist incentives to take intellectual risks, and that academic institutions have incentives to hire and reward scholars who take intellectual risks, despite the caveats mentioned above. These incentives are a major reason tenure exists. In the next three sections, I discuss why widespread self-censorship persists, despite these incentives, and how academic institutions can better promote courageous and free scholarship.

5. Why Academics Self-Censor and Tend to Be Risk Averse

If there are strong incentives to research and speak freely on important topics, as I argue in the previous section, why do so many academics self-censor? I approach this question from two angles. First, I review survey data describing why academics say they self-censor. In other words, what reasons do they give for self-censoring? Second, I summarize broader patterns of academic demographics, social dynamics, and short-term incentives, which provide additional context.

The 2024 FIRE Faculty Survey Report (Honeycutt, 2024) sheds light on the prevalence and nature of self-censorship among U.S. faculty. The survey asked participants to define self-censorship as:

Refraining from sharing certain views because you fear social (e.g., exclusion from social events), professional (e.g., losing job or promotion), legal (e.g., prosecution or fine), or violent (e.g., assault) consequences, whether in person or remotely (e.g., by phone or online), and whether the consequences come from state or non-state sources. (Honeycutt, 2024)

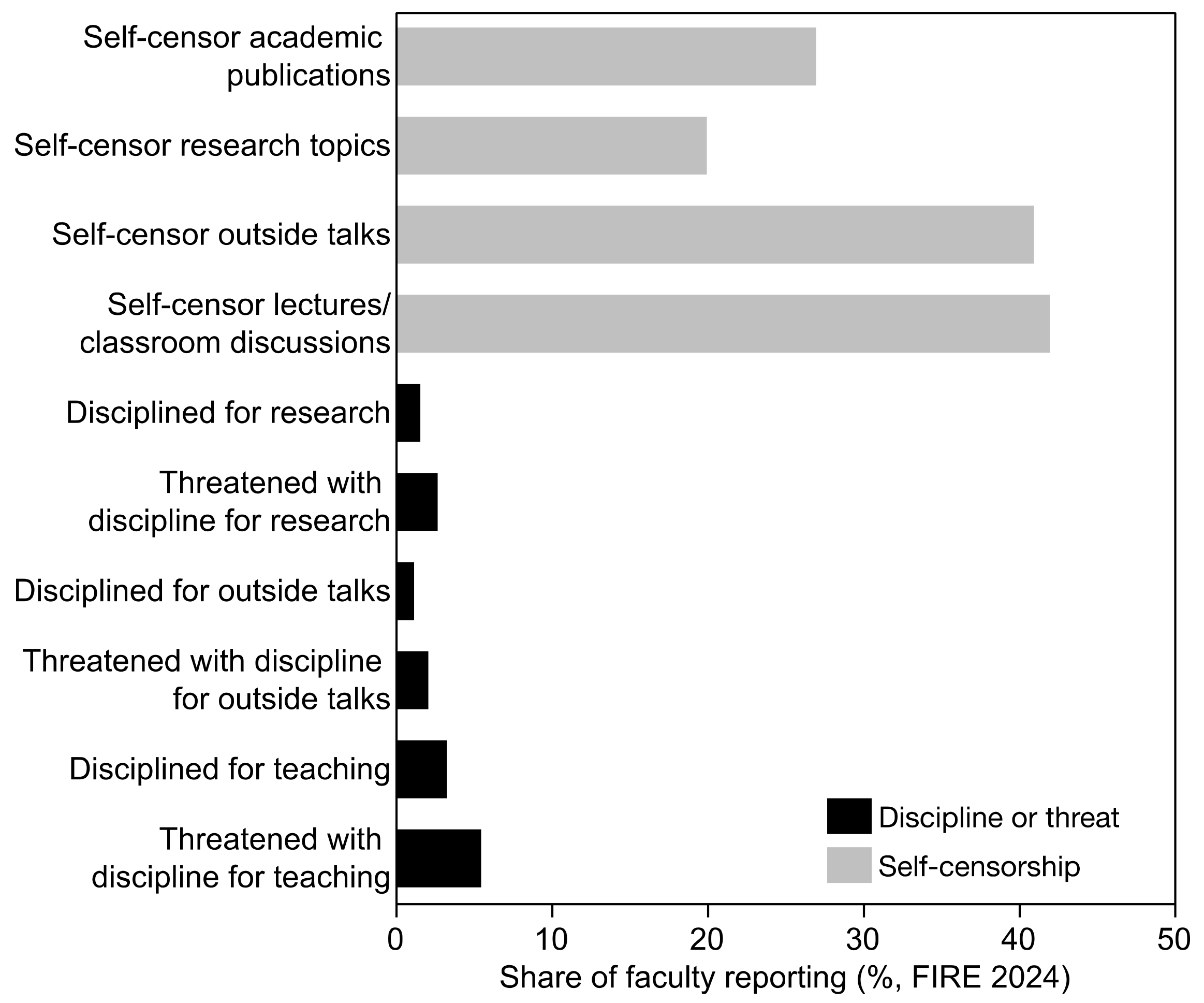

By this definition, 20% of faculty reported self-censoring their research topics; 27% reported self-censoring their academic publications; 41% reported self-censoring their outside talks; and 42% reported self-censoring in classroom lectures or discussions. Moreover, 28% reported at least “occasionally” hiding “their political beliefs from other faculty in an attempt to keep their jobs”; 27% reported feeling that they “can’t express their opinion on a subject because of how other faculty, students, or the administration would respond”; and 40% reported being worried about “damaging their reputations because someone misunderstands something (they) have said or done” (Honeycutt, 2024).

These rates of self-censorship and fear were higher among conservative and moderate faculty, and among faculty without tenure (Honeycutt, 2024). Relatedly, respondents overwhelmingly believed a liberal would be a “positive” fit (71%) rather than a “poor” fit (3%) in their departments, with an opposite pattern for conservatives – 20% stated that a conservative would be a positive fit, compared to 39% stating that a conservative would be a poor fit.

Self-reported rates of being actually disciplined, threatened with discipline, or directly pressured by administration or peers were an order of magnitude lower than self-censorship rates (Figure 5). For example, 1.6% of faculty respondents reported being disciplined for their research, and 2.7% reported being threatened with discipline; 1.2% reported being disciplined for their outside talks, and 2.1% reported being threatened with discipline; 1.6% reported being disciplined and 3% reported being threatened with discipline for their non-academic speech and writing; 3.3% reported being disciplined, and 5.5% reported being threatened with discipline, for their teaching (Honeycutt, 2024). FIRE did not report the breakdown of these responses by political affiliation, but conservative faculty report higher rates of discipline and threats of discipline for their research and views in other surveys (e.g., Kaufman, 2021). The FIRE survey (Honeycutt, 2024) also did not ask if the self-reported discipline or threats were specifically related to the content of the research and teaching, as opposed to other research and teaching infractions unrelated to academic freedom. The self-reported discipline and threat rates therefore could be an upper bound on the scale of censorship. Most faculty reported not being pressured by their administration (85% “never”, 10% “rarely”) or peers (79% “never”, 12% “rarely”) to avoid researching controversial topics (Honeycutt, 2024).

Figure 5.

A comparison of self-reported self-censorship and actual censorship (discipline or threats of discipline), from the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE)’s 2024 Faculty Survey Report (Honeycutt, 2024).

Figure 5.

A comparison of self-reported self-censorship and actual censorship (discipline or threats of discipline), from the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE)’s 2024 Faculty Survey Report (Honeycutt, 2024).

The above data underscore the fact that fears of censorship, pressure, and sanctions are much more prevalent than actual censorship, pressure, or sanctions. Logically, there are two possible explanations for this. One is that self-censorship is so pervasive that there are too few transgressions left for the would-be censors to punish. Under this explanation, most faculty transgressing against prevailing orthodoxies are sanctioned, but faculty rationally self-censor to avoid sanction, leaving few transgressors remaining to be sanctioned. The second possible explanation is that many faculty who self-censor would not actually be sanctioned, and/or would gain professionally more than they suffered, were they to speak freely.

A mixture of these two dynamics likely occurs in reality. The historically large numbers of censored academics – even though a relatively small fraction of academics – undoubtedly motivate some of the self-censorship. How could they not? They also reduce the number of academics transgressing against orthodoxies. On the other hand, there are clearly many professors who self-censor transgressive speech, research, and teaching that they would not likely have been sanctioned for. Consider, for example, the fact that a large majority of faculty report no pressure from administrators to censor their research (see above), but many self-censor anyway (Figure 5). Consider also the many academics who do speak, research, and teach transgressively who are not sanctioned and/or realize net benefits to their careers from doing so, as I discussed in the previous section.

Even if the odds of sanction are small, it is natural to avoid small risks of potentially life-altering outcomes such as job loss. In a recent book, psychologist Kurt Gray (2025) argues that humans may have evolved to have risk-averse mindsets due to our evolutionary history as prey. In this light, self-censoring to avoid a small chance of losing one’s job is no less rational than avoiding dark alleys at night to avoid a small chance of being attacked. As the FIRE survey suggests (Honeycutt, 2024), self-censorship is also often motivated by non-catastrophic professional or social fears, such as ostracism or reputational damage (affecting student recruitment, speaking invitations, and other professional activities), from which tenure does not offer protection.

However, surveys have found that academics self-censor (and desire to censor others) at a higher rate than other Americans, on average, despite academics having, in most cases, much greater speech protections in law and policy than are found in other professions (Al-Gharbi, 2019, 2024a; Clark et al., 2024). This suggests that there may be something about the social dynamics and incentive structures of academia that promotes self-censorship, in addition to the basic fear of punishment.

Indeed, some of the structures of academia seem to produce selection incentives and short-term career incentives that promote risk-averse behaviors. Peer review, shared governance, the insularity of many disciplines and sub-disciplines, and the job security of tenure (meaning one expects to be working with the same colleagues for decades) all create incentives for conformism (Al-Gharbi, 2025). Studies have found that professions with low pay variance, less performance-based pay, public-sector professions, and teaching professions (including the professoriate) attract risk avoiders, on average (Dohmen & Falk, 2010; Grund & Sliwka, 2010). Most tenured and tenure-track professorships have these characteristics attractive to risk avoiders, though the earlier stages of academic careers have become riskier and more precarious in recent decades.

Higher education teachers and professional researchers also score highly relative to other professions in the Big-Five personality trait neuroticism (Anni et al., 2024), which is associated with risk avoidance (Ahmed et al., 2022). Big-Five neuroticism is also associated (in its high-functioning forms) with high undergraduate performance (Komarraju & Karau, 2005) – one of the filters typically used to select students into graduate school. However, neuroticism is negatively associated with research performance (Feng et al., 2024), perhaps due to its association with risk avoidance, in contrast to the long-term incentives for risk taking outlined in the previous section.

Neuroticism – associated with high sensitivity to negative stimuli, presumably including offensive ideas – may also be associated with greater willingness to censor other scholars. Researchers have noted the apparent link between university cancel culture and the deterioration of undergraduate mental health (especially among liberals; (Al-Gharbi, 2023a) since the mid-2010s (Lukianoff & Haidt, 2018), for example. Academics self-report greater willingness to censor others than those in other professions, as noted above (Al-Gharbi, 2025). Some scholars have noted trends that may predict increasing levels of neuroticism and risk aversion in the academy in the future, such as increases in both traits among young people over the past decade (Burn-Murdoch, 2025), and average sex differences in both traits combined with changing demographics in the academy (Clark & Winegard, 2022).

In summary, academia creates strong day-to-day incentives for social conformism, and it offers relatively high job and pay security on the tenure track. For these and perhaps other reasons, academia seems to disproportionately attract risk-avoiders, social conformists, and people high in Big-Five neuroticism. These traits may help to explain why academics report self-censoring and desiring to censor others at higher rates than other Americans. Ironically, tenure – which creates the job security that may be helping to attract risk-avoiders to the academy – was intended to protect risk-takers.

Policy uncertainty creates another incentive that seems relevant to understanding the prevalence of self-censorship in academia. Universities violating their stated policies or procedures has been a common feature of the forms of cancel culture originating on campus (Lukianoff & Schlott, 2023). Sudden policy changes and punishments meted out under novel legal theories have been common features of the forms of cancel culture originating from government (e.g., see the examples related to Israel–Palestine protests discussed in Section 3). It is axiomatic in economics that unclear rules, lack of rule of law, and uncertainty about future laws prevent investment and harm economic growth. Analogous policy and rule-of-law uncertainties undoubtedly contribute to self-censorship in academia, and they likely also drive away talented prospective academics.

6. Free-Rider Problems, Prisoners’ Dilemmas and Academia’s Crisis of Trust

Self-censorship in academia threatens its core value proposition of knowledge seeking and dissemination. If academics cannot be trusted to pursue and disseminate the truth without fear or partisan favor, academia risks losing the public trust on which academia’s funding and enrollments depend. Conversely, academics who are fearlessly and conscientiously seeking and disseminating truth are providing benefits to academia writ large by contributing to its public trustworthiness. Academics who speak, research, and teach freely may also reduce the personal risks to others of doing so, by normalizing it and making it seem less transgressive.

These dynamics represent free-rider problems and (closely related) prisoners’ dilemma problems that academic institutions have a material incentive to correct. Free-rider problems arise when an individual action has concentrated costs to the actor and diffuse benefits to society. This gives people incentives to “free ride” on the efforts of others who are willing to pay the cost, and it causes fewer people to take the socially beneficial action than would be optimal. Prisoners’ dilemma problems arise when individuals can avoid punishment by cooperating with each other – in this case by exercising their expressive and academic freedoms and thereby making it non-transgressive to do so.

Individual incentive enhancements, policies, or strong social norms are typically needed to overcome free-rider and prisoners’ dilemma problems. For example, to keep public spaces clean and functional, we pay custodial staff and maintenance staff, and we enforce social norms and policies against littering. If we did none of these things, individual citizens would have insufficient incentives to maintain public spaces, because doing so would have private costs and diffuse, public benefits.

Academia’s trust problem is analogous. Researching honestly and openly, and speaking up against pernicious trends in academia, can pose individual risks (as well as the rewards discussed in Section 4), but it also has the diffuse social benefits of encouraging others to do the same, and of preserving academia’s trustworthiness and integrity. Conversely, each time that an academic self-censors, they may be avoiding a risk of short-term conflict, but they are also contributing to others’ self-censorship, and to academia’s march towards a crisis of legitimacy.

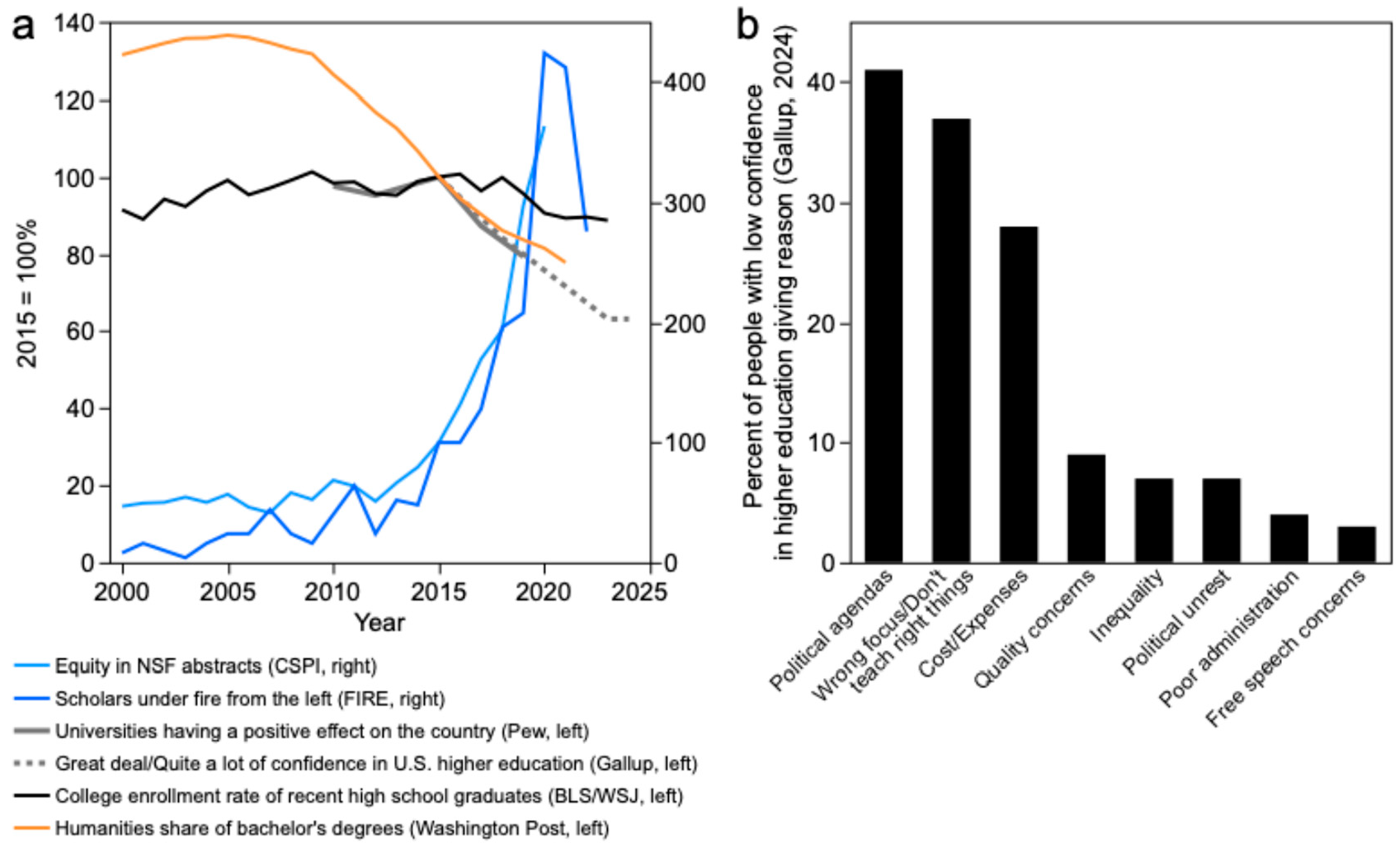

Widespread self-censorship is part of a cluster of self-destructive patterns – each accelerating since the early 2010s – that pose existential threats to academia’s trustworthiness and integrity. Academia’s turn towards scholar-activism, its left-wing monoculture and orthodoxy, its at-times-blatant disregard for federal law (e.g., Sailer & Galarowicz, 2025), and its administrative bloat have caused sharp declines in trust in universities. These trends coincide with declines in humanities enrollment, and, more recently, declines in overall college enrollment, especially among men (Figure 6). The effects of post-2010 academia on broader culture may have contributed to President Trump’s re-election (Al-Gharbi, 2024b). The Trump administration’s recent funding threats and adversarial posture towards academia may be especially aggressive, but many scholars and writers have argued that academia was long headed for a reckoning, one way or another (see, e.g., Jussim, 2025).

Although academia provides enormous value to the economy, innovation, public health, and many other areas of well-being (e.g., Berman, 2025), it is also enormously dependent on public money. By extension, it depends on public trust and legitimacy. The public and their elected representatives are rational to question whether an academia, in which 20-40% of professors self-censor their scholarship (Figure 5), is trustworthy. The public and their elected representatives are also rational to question whether an academia with often-explicit political commitments (Lukianoff & Schlott, 2023; Eppard et al., 2024) – to political views often far outside the American mainstream (Jussim et al., 2023; Teixeira & Judis, 2023; Burn-Murdoch, 2024) – is legitimate.

Therefore, academics deciding whether to self-censor should consider the underappreciated and existential collective risks to doing so, in addition to the underappreciated benefits of free expression and inquiry outlined in Section 4. Academic institutions should consider how to provide even better incentives to academics to exercise their expressive and academic freedoms, recognizing the collective institutional benefits that free expression often provides.

Figure 6.

(Reproduced from Burgess, 2024c) Panel a compares the timing of academia’s “Great Awokening” (Yglesias, 2019) (measured by scholars under fire from the left (FIRE, 2025a) and the frequency of the word “equity” in National Science Foundation (NSF) abstracts (Rasmussen, 2021); other measures show similar patterns (Al-Gharbi, 2023b)) with the timing of declining college enrollments – overall (Belkin, 2024) and in the humanities (Van Dam, 2022) – and declines in public trust in universities (from Pew (Doherty & Kiley, 2019) and Gallup (Jones, 2024)). All data series are compared to their 2015 levels. Panel b shows the reasons Americans gave (to Gallup (Jones, 2024)) for having low confidence in U.S. higher education. “Political agendas” meant one of: “indoctrination/brainwashing/propaganda”, “Too liberal/political”, “Not allowing students to think for themselves/Pushing their own agenda”, “Too much concentration on diversity, equity and inclusion”, or “Too socialist”.

Figure 6.

(Reproduced from Burgess, 2024c) Panel a compares the timing of academia’s “Great Awokening” (Yglesias, 2019) (measured by scholars under fire from the left (FIRE, 2025a) and the frequency of the word “equity” in National Science Foundation (NSF) abstracts (Rasmussen, 2021); other measures show similar patterns (Al-Gharbi, 2023b)) with the timing of declining college enrollments – overall (Belkin, 2024) and in the humanities (Van Dam, 2022) – and declines in public trust in universities (from Pew (Doherty & Kiley, 2019) and Gallup (Jones, 2024)). All data series are compared to their 2015 levels. Panel b shows the reasons Americans gave (to Gallup (Jones, 2024)) for having low confidence in U.S. higher education. “Political agendas” meant one of: “indoctrination/brainwashing/propaganda”, “Too liberal/political”, “Not allowing students to think for themselves/Pushing their own agenda”, “Too much concentration on diversity, equity and inclusion”, or “Too socialist”.

The recent attacks on academia by the Trump administration may also be creating new free-rider problems for institutions. For example, there may be significant financial risks to any institution that challenges the legality of the administration’s funding ultimatums (against Harvard and Columbia, at the time of this writing) under either the First Amendment or Title VI procedures. However, any institution that wins limits on the federal government’s ability to strip away funding without due process, or to place limits on academic freedom, would be doing the entire academic enterprise a favor. Of course, the federal government should also consider the importance of due process and rule of law to the health of academic institutions (and broader society), especially if law-breaking by universities is one of their motivating concerns.

7. Recommendations for Policymakers and Academic Institutions

The previous sections have focused on exploring the underappreciated rewards academics can receive for inquiring freely and being intellectually courageous, as well as the underappreciated risks to the academic enterprise from continued collective self-censorship. My implied advice for individual scholars is to speak, research, and teach more freely. Governments and academic institutions can also improve (or diminish) scholars’ incentives for free expression and inquiry. I will not attempt to chart an exhaustive agenda for institutional and policy reform, as that would be beyond the scope of this paper. However, I will briefly offer three simple recommendations for academic institutions and/or policymakers.

Make clear rules and follow them. As mentioned in Section 5, policy uncertainty and lack of rule of law can be major barriers to free expression, as well as confidence, trust and investment. Both governments and university administrations have sometimes contributed to recent chilly speech climates in academia by not following their stated rules, or by rapidly and unpredictably changing the rules or how they are enforced, often without due process or clear explanation. Universities’ inconsistent enforcement of their rules protecting speech, prohibiting race and gender discrimination, and prohibiting disruptive or violent protests provide three widespread examples that have been reported on in the media. The federal government’s recent crackdown on non-citizen scholars’ speech provides a salient example on the government side. DEI requirements for research grants provide another government example, touching both sides of the political spectrum. During the Biden administration, grant proposals often were required to have DEI components to be funded (e.g., under Executive Order 13985 (The White House, 2021)). Under the new Trump administration, grants are being canceled for having DEI components (e.g., under Executive Order 14151 (The White House, 2025)). This creates a catch-22 for researchers.

While I hope that governments and universities will strengthen rule of law on their own, the country’s systems of checks and balances can also reinforce this. For example, governments can and should hold universities accountable (subject to due process) when they violate laws relating to speech, discrimination, or upholding their contracts. Courts have an important role to play in holding both universities and governments accountable when they fail to uphold their laws, policies, or due process. Civil liberties groups can support scholars’ individual rights through advocacy and litigation.

Reward integrity and intellectual courage. As Section 4 and Section 5 above discuss, academia disproportionately benefits from intellectual risk-takers, and it disproportionately attracts risk-avoiders. This suggests that academic institutions could greatly benefit themselves and the academic enterprise by adjusting hiring, promotion, awards, and other incentives to reward intellectual courage more. Relatedly, academia’s trust problem would be ameliorated if academic institutions placed greater premiums on intellectual integrity.

For example, hiring and promotion committees – and perhaps even journal editors – could explicitly note and reward studies’ and scholars’ implied courage and integrity in similar ways as they currently note and reward novelty and creativity. Courage and integrity are subjective, of course, but so are novelty and creativity. Conversely, hiring and promotion committees could penalize academics who have participated in attempts to censor their peers’ scholarship (as opposed to merely publicly criticizing peers, which should not be discouraged, of course). Major academic institutions, such as the U.S. National Academies, could create awards for courage and integrity, like those that they currently give out for science communication (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2025). Academic institutions could build values like viewpoint diversity, open inquiry, and constructive disagreement (Heterodox Academy, 2025) into their vision statements and strategic plans, which would create downstream incentives to promote and reward these values.

Whatever the specific mechanism, if institutions send salient policy signals that intellectual courage and integrity are being rewarded – and that censorious and intellectually dishonest behaviors are being discouraged – these signals would become self-reinforcing via social norms. Recognizing self-censorship as a free-rider problem (see Section 6) would help, too. We do not reward and seek out free riders in other domains; why should we continue to do so in academia?

A shift towards intellectual courage and integrity in hiring and incentives is perhaps especially important for administrators. Administrators tend to have less job security and face more public scrutiny than tenured faculty. Administrators thus need more intellectual courage to be able to uphold their intellectual integrity. Academic administrators’ (and other leaders’) lack of courage is often publicly lamented (e.g., Weiss, 2021; New York Times Editorial Board, 2025). Yet, hiring committees often seem to reward candidates who promise to avoid controversy and to keep their schools out of the news – in other words, to keep their heads down.

It is, of course, not desirable to have administrators who recklessly cause controversy, and protecting controversial speech or scholarship by students and faculty members can sometimes have adverse short-term consequences (e.g., loss of donors or student applications). However, the negative long-term consequences of not protecting students’ and faculty’s academic freedom rights tend to be larger. The recent loss of trust and consequent governmental threats to academic institutions illustrate this contrast starkly.

Therefore, while hiring committees for administrators should still reward tact, they should probably put a much greater premium on courage and integrity than many currently seem to. The same principle applies to individual candidates for leadership positions: scholars who do not have the courage to lead should not sign up for leadership positions.

Restore and strengthen meritocracy. Section 4 above reviews evidence that intellectual courage brings success in research and intellectual impact, on average. Section 5 reviews evidence that self-censorship and lack of intellectual diversity in academia (e.g., with respect to conservatives) are exacerbated by social pressures to fit in and get along with scholarly peers. This suggests that academic reward systems (recruitment, hiring, awards, etc.) that emphasize academic excellence will select for intellectual courage, on average. In contrast, academic reward systems that promote nebulous concepts such as ‘fit’ or ‘culture fit’, agreeableness, or social-ideological signaling (e.g., DEI statements) will select for conformism and intellectual cowardice. Therefore, restoring a focus on meritocracy within academic institutions will likely promote intellectual courage and integrity, and reduce self-censorship, among other benefits (Abbot et al., 2023). Governments and policymakers can nudge academic institutions in this direction by strictly enforcing laws against non-meritocratic hiring practices such as race and gender discrimination (e.g., under Titles VI and VII of the Civil Rights Act) and political discrimination (e.g., under the First Amendment).

8. Conclusion

Free speech on U.S. campuses is facing generational threats, coming from both the political left and right, and from both on and off campus (Figure 1). Yet, U.S. academics – especially tenured and tenure-track professors – have some of the strongest free speech protections of any professionals in the history of the world. As I have discussed here, U.S. academics also have stronger career incentives rewarding intellectual courage than many of us realize. Our trustworthiness, legitimacy, and value to society are dependent on our intellectual integrity, which self-censorship and politicization erode. For many academics, our institutions losing their public trust, legitimacy, and enrollments may pose a much greater threat to our careers than individual threats of censorship.

To put it bluntly: our integrity is our most precious asset. If we relinquish our integrity to ideology or fear, then we do not deserve the public’s trust, its respect, or its money. We are lucky to work in one of the expressively freest professions, in one of the expressively freest societies, in the history of the world. Yet, our freedom of expression is only useful – to ourselves and society – if we have the courage to use it.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbot, D.; Bikfalvi, A.; Bleske-Rechek, A. L.; Bodmer, W.; Boghossian, P.; Carvalho, C. M.; Ciccolini, J.; Coyne, J. A.; Gauss, J.; Gill, P. M. W.; Jitomirskaya, S.; Jussim, L.; Krylov, A. I.; Loury, G. C.; Maroja, L.; McWhorter, J. H.; Moosavi, S.; Schwerdtle, P. N.; Pearl, J.; West, J. D. In defense of merit in science. Journal of Controversial Ideas 2023, 3(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, S. J.; Khalid, A. Are colleges and universities too liberal? What the research says about the political composition of campuses and campus climate; American Enterprise Institute, 2020; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Adams, R. Cambridge college sacks researcher over links with far right. The Guardian. 2019. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Ahmed, M. A.; Khattak, M. S.; Anwar, M. Personality traits and entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of risk aversion. Journal of Public Affairs 2022, 22(1), e2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gharbi, M. Comparing perceived freedom of expression on campus v. off. 2019. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Al-Gharbi, M. How to understand the well-being gap between liberals and conservatives. American Affairs. 2023a. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Al-Gharbi, M. The ‘Great Awokening’ is winding down. 2023b. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Al-Gharbi, M. We have never been woke: The cultural contradictions of a new elite; Princeton University Press, 2024a. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Gharbi, M. A graveyard of bad election narratives symbolic capital(ism). 2024b. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Al-Gharbi, M. Mechanisms of censorship in academia; USC Censorship in the Sciences Conference, 2025; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- American Arbitration Association Arbitrator’s Findings & Award. University of New Hampshire Law Faculty Union-NEA-NH and University of New Hampshire Board of Trustees. 2024. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Anni, K.; Vainik, U.; Mõttus, R. Personality profiles of 263 occupations. Journal of Applied Psychology 2024, 110(4), 481–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkin, D. Why Americans have lost faith in the value of college. Wall Street Journal. 2024. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Berman, J. To kill a university. The Harvard Crimson. 2025. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Burgess, M. How polarization will destroy itself. Guided Civic Revival. 2024a. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Burgess, M. It’s time to stop the double talk around diversity hiring. Chronicle of Higher Education. 2024b. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Burgess, M. Trump Administration can save American education—Here’s how; Konstantin Kisin, 2024c; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Burgess, M. G.; Ritchie, J.; Shapland, J.; Pielke, R. IPCC baseline scenarios have over-projected CO2 emissions and economic growth. Environmental Research Letters 2021, 16(1), 014016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burn-Murdoch, J. Trump broke the Democrats’ thermostat. Financial Times. 2024. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Burn-Murdoch, J. The troubling decline in conscientiousness. Financial Times. 2025. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Chronicle of Higher Education. DEI legislation tracker. 2025. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Clark, C. J.; Fjeldmark, M.; Lu, L.; Baumeister, R. F.; Ceci, S.; Frey, K.; Miller, G.; Reilly, W.; Tice, D.; von Hippel, W.; Williams, W. M.; Winegard, B. M.; Tetlock, P. E. Taboos and self-censorship among US psychology professors. Perspectives on Psychological Science 2024, 20(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.; Winegard, B. Sex and the academy. Quillette. 2022. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Cofnas, N. Four reasons why Heterodox Academy failed; National Association of Scholars, 2022; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Crisp, R.; Dasgupta, P.; Daouda, M.; Elbourne, P.; Glover, J.; Hughes, C.; Kramer, M.; Leiter, B.; McMahan, J.; Minerva, F.; Pinker, S.; Plomin, R.; Singer, P.; Srinivasan, A. Defence of free speech. The Times. 2024. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Cullen, S. Dangerous ideas in science and society; Carnegie Mellon University, 2021; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Cutter, C.; Glazer, E. The latest dirty word in corporate America: ESG. Wall Street Journal. 2024. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Doherty, C.; Kiley, J. Americans have become much less positive about tech companies’ impact on the U.S. Pew Research. 2019. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Dohmen, T.; Falk, A. You get what you pay for: Incentives and selection in the education system. The Economic Journal 2010, 120(546), F256–F271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreger, A. Galileo’s middle finger: Heretics, activists, and one scholar’s search for justice; Penguin Books, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Efimov, I. R.; Flier, J. S.; George, R. P.; Krylov, A. I.; Maroja, L. S.; Schaletzky, J.; Tanzman, J.; Thompson, A. Politicizing science funding undermines public trust in science, academic freedom, and the unbiased generation of knowledge. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics 2024, 9, 1418065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppard, L. M.; Mackey, J. L.; Jussim, L. (Eds.) The poisoning of the American mind; University of Virginia Press, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, R.; Xie, Y.; Wu, J. How is personality related to research performance? The mediating effect of research engagement. Frontiers in Psychology 2024, 14, 1257166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FIRE. FIRE statement on Florida’s expansion of the Stop WOKE Act. 2023. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- FIRE. Wingate University: Professor fired for protected speech on social media. 2024. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- FIRE. Scholars under fire database. 2025a. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- FIRE. FIRE and coalition partners file brief rebuking the U.S. government for attempting to deport Mahmoud Khalil for his protected speech. 2025b. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Flaherty, C. Risky research. Inside Higher Education. 2020. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Gerber v. Ohio Northern University, et al. 1107 CVH, Common Pleas Court of Ohio, 2409112. 2023. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Gluhanich, H. No speech for you: College fires professor for calling America ‘racist fascist country’ in email to students; FIRE, 15 January 2025; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Goldberg, E.; Krolik, A.; Boyce, L. How corporate America is retreating from D.E.I. New York Times. 2025. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 21 October 2025).