Controversial_Ideas , 5(3), 2; doi:10.63466/jci05030013

Article

Is Gender Affirming Care the Latest Example of the Politicisation of Psychiatry?

Queensland Children’s Hospital, Australia; jillian.spencer@ihms.com.au

How to Cite: Spencer, J. Is Gender Affirming Care the Latest Example of the Politicisation of Psychiatry?. Controversial Ideas 2025, 5(3), 2; doi:10.63466/jci05030013.

Received: 10 September 2025 / Accepted: 15 September 2025 / Published: 11 November 2025

Abstract

:Objective: To stimulate debate as to whether gender affirming care is a governmental policy imposed upon psychiatrists in the early decades of the 21st century. Conclusion: Gender affirming care (GAC) is a highly controversial treatment approach for minors with gender distress. GAC possesses several unique features that potentially mark it as a political movement rather than a health intervention, including: its availability according to government policy rather than research evidence, clinicians being under perceived pressure to implement GAC, the required use of visual symbols and language to signal allegiance to the model in the workplace, and the involvement of activist organisations in guiding its implementation in health services. GAC aligns with historical examples of the politicisation of psychiatry in providing a sanitising cover for governments to enact an unpopular political agenda without appearing to rely upon overt forms of authoritarianism. Disguising GAC as a psychiatric treatment successfully stymied public debate by suggesting that psychiatrists have a degree of medical expertise regarding gender distress that the public lacks. Clinician dissidents to GAC face social pressures and fear risks to their employment and medical registration. Two recent Family Court judgments in Australia further demonstrate the mechanisms by which GAC is held in place by activist clinicians supported by a governmental agenda.

Keywords:

gender affirming care; adolescents; politicisation of psychiatry; Family CourtIntroduction

Within Australia, the field of psychiatry spearheaded the implementation of the gender affirming care (GAC) treatment model for children and young people with gender distress. According to this model, being trans or gender diverse is part of the natural spectrum of human diversity and affirmation of a young person’s gender via social, medical or surgical interventions is helpful and even ‘medically necessary’ (Coleman et al., 2022). The model considers the high rates of mental health problems in children and adolescents claiming a trans identity to be largely the consequence of stigma and social exclusion (Coleman et al., 2022). According to this perspective, one would expect a child’s gender distress, along with any comorbid mental health problems, to improve or resolve as a consequence of gender-affirming interventions. However, systematic reviews have concluded the evidence for such benefits is very weak and subject to bias and confounding factors (Cass, 2024b; Miroshnychenko, 2025). The long-term health implications of the GAC pathway for children can be profound: infertility or reduced fertility, reduced or absent sexual functioning, physical health complications and the risk of regret (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2025).

GAC proposes the outcome of ‘aligning the body with the gender identity’ (Coleman et al., 2022). According to this model, a patient is ‘affirmed’, that is, they are treated as if they are the sex with which they identify. However, a person cannot change sex despite adopting the gender identity of someone of the opposite sex: Sex is binary and defined by males having a reproductive system which produces small, mobile gametes (sperm), whereas females have a reproductive system which produces immobile, large gametes (eggs) (Sullivan & Todd, 2023).Therefore, a belief that people should be regarded as being of the sex with which they identify is a political concept, not a scientific concept.

The History of the Politicisation of Psychiatry

Political ideology can be defined as a set of beliefs about the proper order of society and how it can be achieved (Erikson & Tedin, 2015). A political movement develops when an idea for societal change comes to be held by an increasing number of people. Individuals in the movement may have differing personal or professional, conscious or unconscious, reasons for seeking the proposed societal change. The proposed societal change may be ultimately enacted by government, ideally, but not necessarily, with democratic assent. Political goals may be hidden behind a claimed acceptable goal. For example, colonialism had a civilising mission as its façade, but economic objectives underlying (Cormier, 1966).

Politicisation means to mark an issue as an object or a topic of political action (Wiesner, 2021). Politicisation of a professional discipline subverts the discipline’s normal processes and ethical frameworks.

The politicisation of psychiatry by governments has been recognised since at least the 1970s (Kosenko & Steger, 2023). Reports of politicisation have come from a wide range of countries, suggesting that using psychiatry to enact governmental policy is a well-worn strategy. In 1977, in response to the politicisation of psychiatry in the USSR, the World Psychiatric Association developed the first Code of Ethics for Psychiatry (Kosenko & Steger, 2023). Among other principles, it stated that, ‘if a patient or some third party demands actions contrary to scientific knowledge or ethical principles the psychiatrist must refuse to cooperate’ (World Medical Association, 1978).

Buoli and Giannuli (2017) saw that, historically, government use of psychiatry to achieve political ends escalates when governments seek to avoid an authoritarian image. Reflecting on historical examples, Kosenko and Steger (2023) warn that, for psychiatry to be politicised, at least some psychiatrists who agree with the government’s agenda need to actively participate in the politicisation.

The most well-known historical example of the politicisation of psychiatry occurred in the USSR. Through the 1960s and 1970s, forensic psychiatrists participated in institutionalising citizens who had developed economic and social theories in opposition to the Soviet regime (Kosenko & Steger, 2023). Political dissidents were diagnosed with ‘sluggish schizophrenia’, a concept more akin to personality disorder (Smulevich, 1989). The diagnosis emerged from the idea that there was no logical reason to oppose the best sociopolitical system in the world (Van Voren, 2010). As expressing dissent was punished by internment in a labour camp for three years, psychiatrists may have considered institutionalisation a kinder alternative (Wing, 1974).

Another well-known example of the politicisation of psychiatry occurred under the Ceausescu Communist regime in Romania between 1965 and 1989 (Adler et al., 1993). Psychiatrists were required to be members of the party to be eligible to work. A minority of psychiatrists became activist participants in the aims of the government. In advance of important communist events, the Ceausescu government would deposit large numbers of political dissidents in psychiatric hospitals. Psychiatrists also were compelled to institutionalise and provide involuntary psychotropic medication to dissidents.

Politicisation of psychiatry is reportedly continuing to occur in China with psychiatric institutionalisation of followers of the Falun Gong movement (Appelbaum, 2001). Most infamously, in Nazi Germany, psychiatrists had the role of identifying individuals with psychiatric disabilities under the ‘euthanasia program’ with its political goal of the creation of a physically and mentally ‘perfect race’ (Strous, 2007). Less controversially, psychiatry continues to be exposed to political influences through legislation setting the threshold for involuntary mental health treatment.

Gender Affirming Care as a Political Movement

A recent Australian federal Family Court judgment considering the case of a 16-year-old female seeking testosterone where one parent did not consent, recognised GAC as a policy of the State Government, with gender clinic clinicians mandated to provide GAC in line with the policy (Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia, 2024). This differs from other mental health interventions that are not imposed on clinicians with the force of government policy.

It is untested in Australia whether a governmental health service can enforce a treatment approach upon its clinicians. I was suspended from my job as a child psychiatrist at the Queensland Children’s Hospital in April 2023 due to an accusation of not following a lawful direction given to me by the hospital executive that I must always take an affirming approach towards children with gender distress. I was given the lawful direction after telling my employer that I did not want to immediately use the preferred pronouns of child and adolescent patients. Prior to this, I had no workplace or performance issues and had been employed within Queensland public health facilities for over twenty years. I remain suspended. To my knowledge, my situation is unprecedented, suggestive of political elements at play rather than usual disciplinary processes. I have embarked upon legal action to clarify the lawfulness of the hospital’s lawful direction. In the interim, each clinician faces an individual decision whether to comply with their institution’s work instruction or model of care documents specifying an affirming approach.

Particularly for clinicians working in the private mental health sector, conversion therapy legislation in some states of Australia (Government of South Australia, 2024; Parliament of New South Wales, 2024; Parliament of Victoria, 2021; Queensland Parliament, 2005) appears to apply pressure, in the form of perceived legal threat, to prevent practitioners from taking an exploratory, non-affirming approach.

Originally, conversion therapies referred to any treatments, including individual psychotherapy, behavioural (including aversive stimuli), or group therapy which attempt to change an individual’s sexual orientation from homosexual to heterosexual. However, a surge of worldwide conversion therapy legislation over the last decade further included bans on practitioner attempts to change or suppress gender identity. These bans do not allow leeway for patient age.

That conversion therapy legislation functions as an effective deterrent against practitioners providing exploratory therapy for children with gender distress was noted in a 2025 Family Court of Australia judgment in which a father advised the court, under oath, that he had contacted hundreds of therapists, without success, in his effort to find an exploratory, non-affirming therapist for his child with gender distress (Family Court of Australia, 2025). This is despite the relevant state conversion therapy legislation allowing health practitioners to exercise ‘reasonable professional judgment’ and provides some leeway for identity exploration (Parliament of Victoria, 2021).

GAC appears to be part of a suite of progressive political measures instituted over the past decade in Australia, along with so-called ‘conversion therapy’ legislation and self-sex identification (The Equality Project®, 2020). Superficially, the policies appear driven by a prioritisation of individual freedoms as ‘human rights’. They appear to resonate with people who see themselves as ‘progressive’ or ‘left wing’ and who are seeking the elevation of minority groups. They may appeal to people who seek a more secular community value system. However, the policy impact is counter to the rights of children to be protected from medical harm. It also undermines the concept of same-sex attraction, with children potentially deprived of the opportunity to become gay men or lesbians (Littman, 2021). The underlying agenda of such policies is debatable.

In Australia, the availability of gender-affirming hormonal interventions to minors appears to vary according to state government policy rather than health research. Restrictions upon new prescriptions of hormonal interventions to minors with gender distress exist in only one state, which is the only state with a centre-right majority government (Queensland Government, Queensland Health, 2025).

An element of GAC indicative of its political basis is the prominence of transgender pride flags and other visual symbols, such as rainbow lanyards and ally/pronoun badges, in medical workplaces (Dell et al., 2022). These serve to signal allegiance to the belief that people can change sex and should be celebrated for undertaking interventions to change their outward appearance. Visual symbols create an imposing presence in the workplace to staff not politically aligned. To date, other health conditions and diseases have not been associated with flags or visual symbols in the workplace.

GAC also differs from other mental health conditions in requiring clinicians to adopt new language, for example, terms such as ‘sex assigned at birth’, ‘gender identity’, ‘cisgender’ and ‘nonbinary’. The terms are repeatedly defined in various documents, journal articles and education programs for clinicians. The terms incorporate an unproven theoretical concept which is politically momentous: that people should be dealt with according to a claimed gender identity and not biological sex. Changes in language appear to be an attempt to embed this political concept in clinicians’ minds. The use of the prescribed language signals a clinician’s allegiance to the political ideas in the workplace and places other clinicians under social pressure to conform. Preferred pronouns differ from being a mere courtesy because they are an essential element of the affirming treatment approach. Preferred pronouns only became mandated as part of the imposition of the GAC treatment approach upon clinicians. In addition, preferred pronouns are clinically impactful, especially for children. The long-term implications of early childhood social transition are poorly understood (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2025).

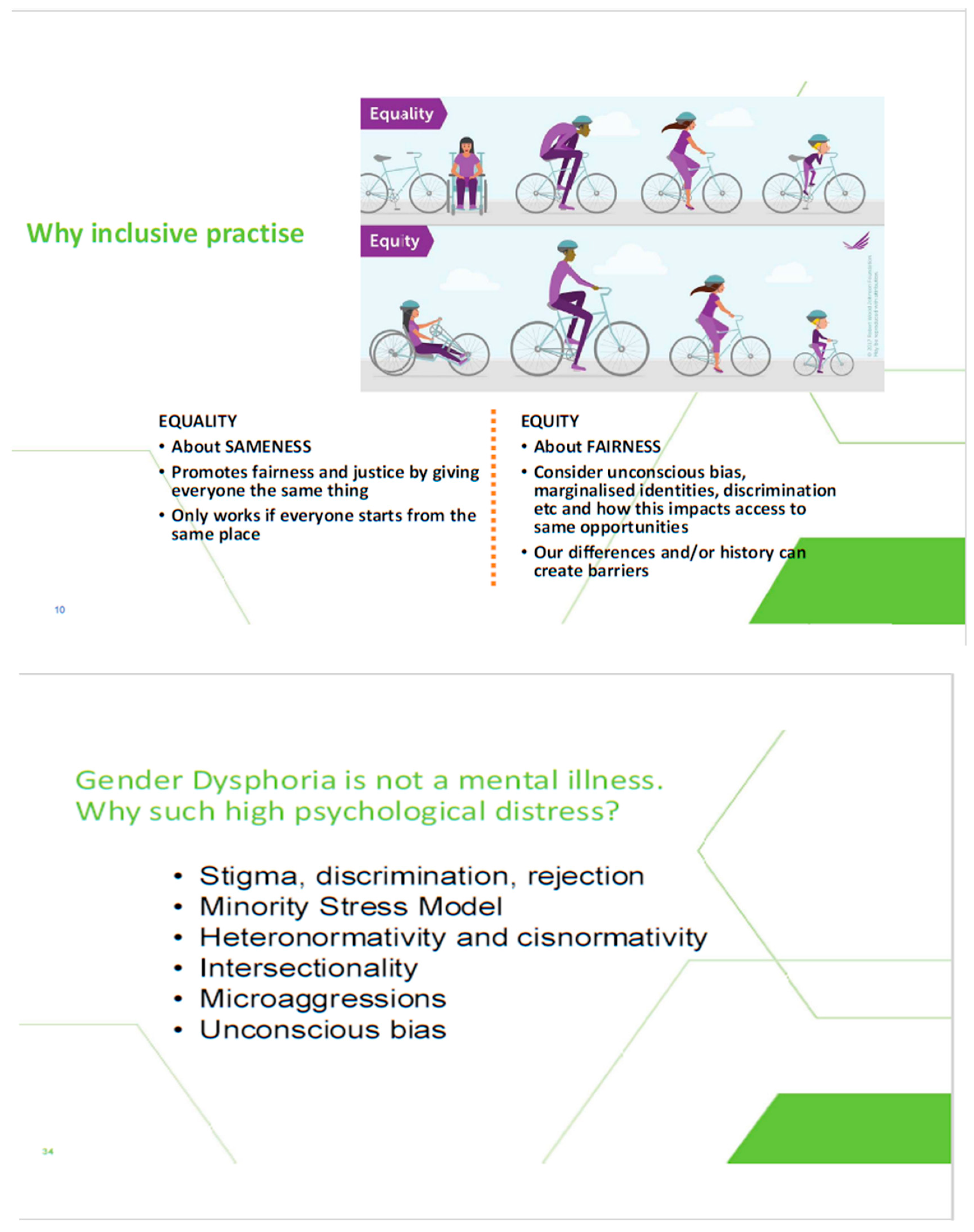

As GAC gained support in Western democracies through the 2010s, its connection to a political agenda became more overtly expressed. For example, presentations on GAC provided at the Queensland Children’s Hospital for ‘Wear It Purple Day’, included the promotion of related political ideas about power, concepts such as ‘cisheteronormativity’, ‘intersectionality’ and the benefits of ‘equity’ over ‘equality’ (see Figure 1). Political concepts are not usually presented in clinical discussions of health conditions. Governmental human rights bodies have also been pivotal in promulgating the idea that teachers are legally obliged to comply with social transitioning children out of respect for their ‘human rights’ (Queensland Human Rights Commission, 2024).

Figure 1.

Political messages provided by the Queensland Children’s Gender Service within a presentation on GAC for Wear It Purple Day 2023.

Figure 1.

Political messages provided by the Queensland Children’s Gender Service within a presentation on GAC for Wear It Purple Day 2023.

Public sector employers mandating clinicians to use a child’s preferred pronouns in clinical interactions, meetings and documentation is an assessable measure of clinician allegiance. In clinical interactions, it interferes with the clinical relationship with the child’s family, as it signals that the clinician is not willing to explore the child’s relationship to their biological sex. In this way, the clinician, functioning as an ‘expert’, imposes the political agenda onto parents. A narrative about greater suicide risk without affirmation that lacks evidence is used as leverage in achieving parental acquiescence to the provision of GAC to their child (Telfer et al., 2023). Where one parent disagrees with recommended affirming interventions, the gender clinic will utilise its state government resources to launch Family Court proceedings seeking permission to provide affirming interventions against the non-consenting parent’s wishes. In addition, there are exceptional cases of the state removing children from parents who declined to affirm their child’s claimed gender identity (Middap, 2025).

A key mechanism by which psychiatry became politicised on this issue was the role of political activist organisations masquerading as health organisations (Spencer & Clarke, 2025). The Australian Professional Association for Trans Health (AusPATH) describes itself a ‘national peak body’ (Australian Professional Association for Trans Health, n.d.). In Australia, a ‘peak body’ is a non-governmental organisation that represents its members who have a common interest in a particular issue. A ‘peak body’ provides advocacy, policy advice, information, professional development, and coordination to government and the public, and develops standards and ethical codes for their sector. AusPATH considers ‘lived experience’ equal to scientific knowledge and admits people with lived experience as full members (Spencer & Clarke, 2025). Valuing ‘lived experience’ stems from the strong consumer movement in Australia that arose out of concern about paternalism in the health profession. The inclusion of people with lived experience as full members allowed political activists to represent themselves as health experts within a health advocacy organisation. Health services then participate in the pantomime, claiming that the ‘expertise’ of AusPATH guides their workplace policies related to GAC.

Health services are under governmental pressure to imbed ‘lived experience’ and LGBTIQ+ ‘experts’ at all levels of service delivery (Victorian State Government, Department of Health, 2021). This has the effect of situating activists within organisations to influence policy and clinical activity and to suppress dissent. In 2024, the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency, which is a governmental body, signed up to the ‘Rainbow Tick’ scheme (Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency National Executive, 2024). This is concerning to practitioners dissenting from gender affirming interventions who are wary of the risk to their medical registration. The Rainbow Tick scheme is a La Trobe University research team wholly funded by the Victorian government. The scheme functions to monitor member organisations’ compliance with requirements of the scheme. For example, organisations are required to ‘ensure … that systems and staff appropriately recognise a person’s identity through affirmed name and pronoun use’ (GLHV@ARCSHS, 2023). Therefore, the government’s medical registration authority is seeking to ensure clinicians comply with directives established by academics aligned with the government’s political agenda.

GAC has been promulgated as a highly sophisticated health intervention strategy. This put it outside any realm of debate among members of the public. Its purported basis in health expertise functioned to set aside reasonable reservations held by the general public based on their own experiential knowledge of childhood and adolescence as a period of immaturity and experimentation. The esoteric nature of psychiatry combined with the public’s respect for psychiatry as a branch of medicine provided cover to normalise the gender transition of children with the public. Using psychiatry for the implementation of GAC took advantage of the community’s trust of doctors, and their concern about the mental health of young people, and allowed for a ‘patient privacy’ argument: that GAC is a private decision between patient and doctor, which hides the reality of it being a political agenda with widespread societal implications.

Implications of Re: Ash (Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia, 2024)

In a published 2024 Family Court judgment Re: Ash (Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia, 2024), Justice Tree unwittingly exposed the means by which the GAC political agenda was enforced on psychiatry in Australia; namely: the use of propaganda, the substitution of new ethical principles, the lauding of clinicians implementing the mandated model, and the denigration of dissidents.

Propaganda is the systematic dissemination of information, especially in a biased or misleading way, to promote a particular cause or point of view, often a political agenda (Oxford University Press, 2007). In the case of gender affirming interventions, the Family Court judgment shows that gender clinician activists continue to promulgate disproven or unproven information to exert influence (See Table 1, which outlines the inaccurate statements made and relevant counter information).

Table 1.

Inaccurate statements in the Family Court judgment (2024) and relevant accurate information

Table 1.

Inaccurate statements in the Family Court judgment (2024) and relevant accurate information

| Inaccurate Statements in Family Court Judgment | Accurate Information |

|---|---|

| The main relevant national and international professional associations support cross-sex hormone treatment for gender dysphoria. (Paragraph 44) | Many professional associations have been politicised and are providing unreliable guidance. The following guidelines and systematic reviews indicate a lack of evidence of benefit from cross-sex hormones:

|

| Randomised controlled trials for cross-sex hormones for the treatment of gender dysphoria would be unethical to perform. (Paragraph 110) | There have been numerous randomised controlled trials (RCTs) undertaken in paediatric medicine. If there is substantial uncertainty about whether a treatment will benefit patients, then RCTs are ethical. The history of paediatric oncology demonstrates that enrolling children and adolescents with rare and life-threatening conditions in high-quality randomised trials is not only possible but also improves outcomes. In response to criticism regarding the ethics of withholding new treatments from the patients randomised to the standard treatment arm of the study, research has shown that new treatments tested in randomised controlled trials are, on average, as likely to be inferior as they are to be superior to standard treatments ζ. |

| WPATH SOC 8 provides the best available guidance for the care of trans and gender diverse people, and people with Gender Incongruence and Gender Dysphoria, across the lifespan, including children and adolescents. (Paragraph 124(a)) | According to the Cass Review Final Report, the WPATH SOC8 did not have sufficiently rigorous development or editorial independence to be a reliable source guiding the treatment of gender dysphoria in paediatric patients η. In addition to the methodological weaknesses, the WPATH SOC 8 recommendations were influenced by non-medical considerations. The Alabama AG amicus brief in the US Supreme Court Skrmetti litigation showed that the US Assistant Secretary of Health Rachel Levine requested that the lower age limits for gender-affirming surgeries be removed. The reason for the removal was to win American litigation to expand access to gender affirming procedures, despite the evidence that those procedures would not improve physical and mental health θ. In June 2024, documents from two US lawsuits showed that WPATH had attempted to institute an ‘approval process’ over manuscripts emanating from the independent systematic reviews it commissioned to develop SOC 8 ι. In August 2020, the Johns Hopkins lead researcher conveyed that that they had found little to no evidence about children and adolescents. However, the SOC 8 chapter on adolescents says there is ‘emerging evidence base indicates a general improvement in the lives of transgender adolescents’. |

| Observational studies (not experimental designs) and must be described as ‘Low Quality’ or ‘Low Certainty’ evidence according to the GRADE approach. Stating that this is “Low Quality” evidence does not mean that the studies are completely useless and uninformative and to be utterly disregarded. That would be a misunderstanding of the terminology used in the discipline of Evidence-Based Medicine. (Paragraph 124(g)) | Observational studies are rated as ‘low quality’ when they have methodological problems making them at high risk of bias. GRADE allows for the quality of an individual observational study to be rated as ‘high’ and the certainty (quality) of evidence to be upgraded if an observational study is well-designed and executed. κ Low-quality or low-certainty evidence should not be 'utterly disregarded' but recommendations based on it should be weak and cautious. |

| There may have been an overt political imperative behind the Cass Review – which was, after all, initiated by the UK executive government. (Paragraph 170) | The Cass Review was initiated by NHS England and NHS Improvement’s Quality and Innovation Committee. δ |

α Finnish Council for Choices in Health Care 2020 guidelines (2020). β National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2020). γ Socialstyrelsen (Swedish) National Board of Health and Welfare (2022). δ Cass (2024b). ε Miroshnychenko (2025). ζ Clayton et al. (2024). η Taylor et al. (2024). θ Supreme Court of the United States (2024). ι Block (2024). κ Djulbegovic and Guyatt (2017).

Replacement of Discipline Ethical Frameworks

Classic medical ethics considers four principles: beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice (Varkey, 2021). However, in the Family Court judgment, a gender clinic clinician substituted a new ethical principle: ‘the dignity of risk’. This term was coined in 1972 by Robert Perske to introduce the concept of assisting people with disabilities to live full and meaningful lives by avoiding over-protection (Perske, 1972). The concept was not intended to apply to children and adolescents making long-term elective medical decisions with the potential of serious long-term consequences to their fertility, sexual functioning and physical health.

Lauding of Clinicians Implementing the Model and Denigration of Dissenters

The judgment demonstrates a concerning consequence of government mandated interventions: those psychiatrists electing to work in gender clinics where they are mandated to enact GAC are considered experts in GAC. The judgment contained several statements lauding the gender affirming psychiatrists’ breadth of clinical experience and statements critical of opposing experts for not having a comparable level of clinical experience. Clinicians expressing dissent to GAC were labelled: ‘a vocal minority’, and denigrated as ‘biased’.

In addition, the judge raised concerns about relying on the findings of the Cass Review Final Report (Cass, 2024a), stating that neither Dr Hillary Cass, nor any review team members, nor the York University researchers conducting the systematic reviews for the Cass Review were called to give evidence so that their conclusions could be directly tested. However, no concern was similarly raised about gender affirming guidelines. The judge stated: “I give… the State Government policy weight, and the Australian Standards of Care (Telfer et al., 2023), Position Statement 103 (Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 2023), and the WPATH SOC 8 [World Professional Association of Transgender Health, Standards of Care Version 8] (Coleman et al., 2022) great weight, because they are models of care arrived at by consensus of the relevant professional bodies”.

Implications of Re: Devin (Family Court of Australia, 2025)

In a 2025 Family Court judgment, Re: Devin (Family Court of Australia, 2025), Justice Strum came to starkly different conclusions about GAC from those in the 2024 Re: Ash judgment. In this case, the judge ordered that a 12-year-old boy have no further contact with a paediatric gender clinic that was recommending the prescription of puberty blockers as part of GAC.

The judgment re-asserted the ethical principles of beneficence and nonmaleficience, and the understanding of childhood as a time of exploration: ‘There are many wonderous and wonderful aspects of childhood, suffused with an innocence that passes with maturity and adulthood. Children may fervently believe, feel and, indeed, wish for many things which may well fall by the wayside as they develop from childhood into adulthood.’

The judgment deemed the Cass Review to be credible and criticised a gender affirming expert witness’s attempt to place the Cass Review in an historical context: ‘The emotive suggestion, by an expert witness, that the Cass Report forms part of a “third wave of transgender oppression” commencing with the Nazis has no place whatsoever in the independent evidence that should be expected of such an expert.’ This expert was later revealed to be Australia’s most prominent proponent of GAC, paediatrician Dr Michelle Telfer (Dudley, 2025). Dr Telfer was further criticised in the judgment for behaving as an advocate rather than as an expert to the court.

The judgment correctly identified the lack of authority behind the ‘Australian Standards of Care’ guideline that underpins GAC practices within all Australian paediatric gender clinics: ‘they do not have the approval or imprimatur of the Commonwealth or any State or Territory Government, including any such government Minister for, or Department of, Health’. The judgment further revealed poor standards of assessment and diagnostic rigour by the gender clinic, despite the child in question having attended the clinic for over four years.

Such formal and public recognition of the serious ethical and clinical concerns posed by GAC, as well as the poor standards of care within the gender clinic, and the lack of objectivity of gender clinic clinicians, was highly significant. However, notably, this Family Court judgment has not led to any state government or health service review of the gender clinic’s functioning, or of the guidelines underpinning the clinic’s model of care, or of GAC itself. Instead, the health service released a statement in support of the clinic and GAC, saying it was ‘proud to lead a Gender Service that delivers a world-leading, multi-disciplinary model of care with a strong emphasis on supporting the mental health and wellbeing of the children and young people referred to our service … Our gender service is underpinned by both national and international research methodology’ (Dudley, 2025).

That GAC has not been reviewed in response to such serious concerns raised by a judge of the Family Court is further evidence that GAC is a political movement rather than a health intervention. It demonstrates the power and impunity of activist clinicians working in accordance with government policy.

Conclusion

GAC has multiple features that suggest that it is a political movement being enacted through psychiatry. Historically, psychiatry has been used to implement government policy and suppress dissent whilst protecting a government from appearing authoritarian. Consistent with historical examples of politicisation, GAC has required the participation of a small group of psychiatrists and other health professionals. Intense pressure to conform to GAC has then been exerted profession-wide through a range of measures.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Statement

The Author declares that no ethics approval was required for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. There were no funders for this manuscript.

References

- Adler, N.; Mueller, G. O.; Ayat, M. Psychiatry under tyranny: A report on the political abuse of Romanian psychiatry during the Ceausescu years. Current Psychology 1993, 12(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appelbaum, P. Law & psychiatry: Abuses of law and psychiatry in China. Psychiatric Services 2001, 52(10), 1297–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency National Executive. Development of a National Scheme LGBTIQA+ equity and inclusion strategy executive summary (Meeting no. 2024-02 NE, Agenda item 6.2), [Document obtained under Freedom of Information; available from author upon request]. 2024.

- Australian Professional Association for Trans Health. Australian Professional Association for Trans Health. n.d. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Block, L. Dispute arises over World Professional Association for Transgender Health's involvement in WHO's trans health guideline. BMJ 2024, 2024(387), q2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buoli, M.; Giannuli, A. S. The political use of psychiatry: A comparison between totalitarian regimes. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 2017, 63(2), 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cass, H. Independent review of gender identity services for children and young people: Final report; NHS England, 2024a. [Google Scholar]

- Cass, H. The Cass Review: Independent review of gender identity services for children and young people: Final report. 2024b. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Clayton, A.; Amos, A. J.; Spencer, J.; Clarke, P. Implications of the Cass Review for health policy governing gender medicine for Australian minors. Australas Psychiatry 2024, 33(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, E.; Radix, A. E.; Bouman, W. P.; Brown, G. R.; de Vries, A. L. C.; Deutsch, M. B.; Ettner, R.; Fraser, L.; Goodman, M.; Green, J.; Hancock, A. B.; Johnson, T. W.; Karasic, D. H.; Knudson, G. A.; Leibowitz, S. F.; Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L.; Monstrey, S. J.; Motmans, J.; Nahata, L.; Arcelus, J. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health 2022, 23(S1), S1–S259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cormier, B. M. On the history of men and genocide. Canadian Medical Association Journal 1966, 94, 276–291. [Google Scholar]

- Dell, A. W.; Robnett, J.; Johns, D. N.; Graham, E. M.; Agarwal, C. A.; Imber, L.; Mihalopoulos, N. L. Providing affirming care to transgender and gender-diverse youth, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing, 2022; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Djulbegovic, B.; Guyatt, G. H. Progress in evidence-based medicine: A quarter century on. Lancet 2017, 390(10092), 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, E. Judge critical of Michelle Telfer over gender guidelines, evidence. The Australian. 5 June 2025. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Erikson, R. S.; Tedin, K. L. American public opinion: Its origins, content and impact; Routledge, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Family Court of Australia. Re Devin [2025] FedCFamC1F 211. 3 April 2025. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia. Re Ash (No 4) [2024] FedCFamC1F 777; 15 November 2024; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Finnish Council for Choices in Health Care 2020 guidelines. 2020. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- GLHV@ARCSHS. The Rainbow Tick guide to LGBTI-inclusive practice, 2nd ed.; La Trobe University, 2023; p. 21. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Government of South Australia. Conversion Practices Prohibition Act 2024; 2024. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Kosenko, O.; Steger, F. Politicization of psychiatry and the improvement of ethical standards in the 1970s. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1151048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littman, L. Individuals treated for gender dysphoria with medical and/or surgical transition who subsequently detransitioned: A survey of 100 detransitioners. Archives of Sexual Behavior 2021, 50(8), 3353–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middap, C. New name, new parents: The teen who divorced her family. The Australian. 10 August 2025. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Miroshnychenko, A. Gender-affirming hormone therapy for individuals with gender dysphoria below 26 years of age: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Evidence review: Gender-affirming hormones for children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. October 2020. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Oxford University Press. Propaganda. In Oxford English Dictionary online, Revised ed.; OED Online, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of New South Wales. Conversion Practices Ban Act 2024 No. 19. 2024. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Parliament of Victoria. Change or Suppression (Conversion) Practices Prohibition Act 2021. 2021. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Perske, R. Dignity of risk and the mentally retarded. Mental Retardation 1972, 10(1), 24–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Queensland Government, Queensland Health. Health service directive: Treatment of gender dysphoria in children. 28 January 2025. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Queensland Human Rights Commission. Trans @ school: A guide for schools, educators, and families of trans and gender diverse children and young people, Rev. ed.; Queensland Human Rights Commission, 2024; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Queensland Parliament. Public Health Act 2005. 2005. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Position statement 103: Recognising and addressing the mental health needs of people experiencing gender dysphoria/gender incongruence; RANZCP, December 2023. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Smulevich, A. B. Sluggish schizophrenia in the modern classification of mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 1989, 15(4), 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socialstyrelsen (Swedish) National Board of Health and Welfare. Care of children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Summary of national guidelines. December 2022. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Spencer, J.; Clarke, P. AusPATH: Activism influencing health policy. Australasian Psychiatry 2025, 33(1), 10398562241312867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strous, R. D. Psychiatry during the Nazi era: Ethical lessons for the modern professional. Annals of General Psychiatry 2007, 6(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, A.; Todd, S. (Eds.) Sex and gender: A contemporary reader, 1st ed.; Routledge; (See Chapter 2: Hilton, E., & Wright, C. Two sexes.); 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Supreme Court of the United States. Brief of alabama as amicus curiae. No 23-477. 2024. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Taylor, J.; Hall, R.; Heathcote, C.; Hewitt, C. E.; Langton, T.; Fraser, L. Clinical guidelines for children and adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence: A systematic review of guideline quality (part 1). Archives of Disease in Childhood 2024, 109 Suppl. 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telfer, M. M.; Tollit, M. A.; Pace, C. C.; Pang, K. C. Australian standards of care and treatment guidelines for trans and gender diverse children and adolescents (Version 1.4); The Royal Children’s Hospital, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- The Equality Project®. Australian LGBTIQA+ policy guide; The Equality Project®; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Treatment for pediatric gender dysphoria: Review of evidence and best practices. 1 May 2025. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Van Voren, R. Abuse of psychiatry for political purposes in the USSR: A case-study and personal account of the efforts to bring them to an end. In Ethics in psychiatry; Helmchen, H., Sartorius, N., Eds.; Springer, 2010; Vol. 45, pp. 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkey, B. Principles of clinical ethics and their application to practice. Medical Principles and Practice 2021, 30(1), 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victorian State Government, Department of Health. Community health pride: A toolkit to support LGBTIQ+ inclusive practice in Victorian community health services. February 2021. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Wiesner, C. Politicisation, politics and democracy. In Rethinking politicisation in politics, sociology and international relations; Wiesner, C., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan, 2021; pp. 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, J. K. Psychiatry in the Soviet Union. British Medical Journal 1974, 1, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Hawaii. Journal of Medical Ethics 1978, 4(2), 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2025 Copyright by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).